by Martina Calì

In the spring of 1509, the League of Cambrai—an alliance promoted a few months earlier by Pope Julius II and consisting of the Holy Roman Empire, France, Spain, and the Papal States—dealt a catastrophic blow to the Republic of Venice at the Battle of Agnadello. The League aimed to destroy Venetian supremacy in northern Italy. After the humiliating defeat, and despite some re-conquests in the following years, the loss of most of its territories prompted the Venetian Republic to reflect on the weaknesses of its political system and the vicissitude of fortune.

The defeat at Agnadello caused significant shifts in Venetian politics. One of them was the recognition by Venetian politicians of the importance of historical knowledge in successful state-building. Subsequently, the Republic began encouraging studies on the League of Cambrai’s wars and appointed an official historiographer in 1516. As Felix Gilbert (1973, p. 290) puts it, the government “took care to restore the School of St Mark, the Venetian center of humanistic studies […] and encouraged those who found in the Roman past lessons for the Venetian present.”

The crisis of Cambrai prompted Venetian patricians to shift from an outlook on politics where the state’s historical development depended on the fluctuations of fortune to one where stability was to be guaranteed by rational principles and educated officers also versed in history. However, even before the League of Cambrai war, some Venetian writers had begun acknowledging the importance of historical knowledge for successful governance. Two writers from that period—Domenico Morosini and Francesco degli Allegri—provided particularly insightful arguments for Venetian politicians concerned with the Republic’s over-expansion and subsequent territorial losses.

Domenico Morosini was born in 1417 and began his career in Venice in 1438, when he was elected capo del sestier, a magistrate responsible for policing duties and supervising the public order in the city. He retained the position in the subsequent years, while between 1441 and 1471, he likely pursued a commercial career (King, 1986, p. 409). After 1471, Morosini assumed several high-ranking offices within the Venetian government and authored the manuscript De Bene Instituta Re Publica (which he started writing in 1497 and never completed), where he devised a model of an ideal merchant republic.

On the other hand, Francesco degli Allegri remains a relatively unknown writer. Born in Verona, he served under Ercole I d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara, before moving to Venice in 1501. There, he wrote Trattato di astrologia, La summa gloria di Venetia, and his Tractato nobilissimo de la Prudentia et Iustitia.

The originality of Morosini and degli Allegri’s writings resulted from their treatment of prudence in economic-financial terms, along with its pairing with ideas of distributive justice. This approach aligned with how the Venetian Senate, Maggior Consiglio and Consiglio di Dieci, discussed these themes in their parti (deliberations) after the defeat at Agnadello. Further, the republican language of degli Allegri and Morosini was reflected in the Commissioni, the official documents describing the tasks required of podestà, Venetian civil governors to mainland towns. The vocabulary of prudence and justice, as basic requirements of newly appointed captains in the cities of the Italian mainland, would be emphasized in the following century in the same types of documents. Therefore, the arguments and ideas circulating in Venice after Agnadello were likely inspired by Morosini and degli Allegri—an observation validating the historical relevance of their political and rhetorical treatises.

Both degli Allegri and Morosini aligned the Ciceronian definition of prudence—as the ability to distinguish good from evil—with that of a rational principle, which regulated governance in the state in a way guaranteeing the equal distribution of resources based on the conditions and merits of citizens. This approach condoned the proportionate distribution of taxes and the appropriate assignment of roles in the government.

Simultaneously, their conceptualization of prudence extended beyond the Ciceronian tradition, which saw prudence as concerning primarily the sphere of choice of an individual. Instead, degli Allegri and Morosini applied the concept of prudence to economy and politics, which partly recovered the Aristotelian view of the practical sphere, where prudence played a paramount role (ϕρόνησις is indeed often translated as “practical wisdom”). According to this view, practical philosophy encompassed three branches: ethics, concerning the individual; economics, focusing on the family and one’s immediate environment; and politics, dealing with citizenship and the organization of society at large. Consequently, when the two Venetian writers discussed prudence in the context of politics, administration, and justice, they espoused Aristotelian categories that emphasized the relevance of prudence as a pivotal social virtue.

The first edition of degli Allegri’s Tractato nobilissimo is not dated within the printed book. However, the edition bears the printer’s mark of Bernardino de Vitalis in Venice within all editions dated 1501. The woodcuts, inserted after the printed text, are dated 1502. Another edition of Tractato, printed in Venice by Melchior Sessa, bears the official date of November 1508. It is possible that additional editions circulated in Venice between 1501 and 1508, and degli Allegri (or the publisher Sessa) felt the need to release new editions of the text due to the political circumstances. In either case, the decision to publish new editions was likely influenced by the increased importance of ideas of prudence and justice in Venetian politics.

Tractato nobilissimo describes an imaginary initiation into poetry undertaken by degli Allegri himself. During this symbolic journey, he encounters the personifications of Prudence and her daughter Justice, portrayed as magnificently adorned women. Prudence, defined in terms of the ability to distinguish between good and evil, explains to degli Allegri the role of reason in the allocation of duties to individuals according to their merits. Consequently, her remark was degli Allegri’s comment on the just distribution of offices in society.

At the time of degli Allegri, the distributiva di cariche was already an established concept in Venetian politics, in which the Great Council regulated the distribution of public offices. However, the term also echoes the Aristotelian notion of distributive justice (NE V.3 1131a 25), which refers to merit since “what is just in distribution must be so according to merit […]. The democrats identify [merit] with the status of freeman, the followers of the oligarchy with wealth (or noble birth), and the followers of the aristocracy with virtue.” For Aristotle, distributive justice was primarily concerned with the distribution of political authority and only secondarily with the distribution of wealth.

It is worth noting the textual tradition in which degli Allegri positioned himself: he clearly modeled his treatise after Albertanus of Brescia’s Liber Consolationis et Consilii from 1246, an extremely influential book during the Italian Renaissance. Degli Allegri’s poem was one of the many vernacular versions of Albertanus’s treatise on the foundations of a good society. The Tractato Nobilissimo represented an adaptation of Albertanus’s text for Venetian readers, referring to the problems of Venetian politics of the time. For instance, degli Allegri did not discuss the main subject of his source—the counsels—or the treatment of vices. Further, Albertanus had not tackled justice, whereas Degli Allegri focused on the fair distribution of offices in society and the problem of disloyal servants of the state: two topics closely related to the administration of justice.

Just as degli Allegri’s associated prudence with the equal allocation of merit, Morosini, in his manuscript De Bene Instituta Re Publica, emphasized the economic and political consequences of a prudent approach to politics, also regarding the relations with mainland Venetian territories. While degli Allegri defined distributive justice in terms of the fair distribution of roles in society, Morosini applied it to the economic sphere, interpreting it as the correct distribution of resources and taxes. Both authors viewed prudence as the guiding principle for achieving a new type of equality regarding the Venetian government and the administration of the Republic.

In De Bene Institute Re Publica, Morosini formulated the model of an ideal republic consisting of three social strata. In his model, the poorest and the richest were excluded from government since Morosini viewed them as prone to factionalism. Hence, it was the middle class who should govern the republic. The main responsibility of the governors was to maintain a flourishing economy, as Morosini considered it the political fulcrum for balancing the needs of the two “extreme” social milieus and guaranteeing the republic’s security. Consequently, the most important role of the state was to administer impartial justice and promote commerce, aiming to prevent potential unrest among both the impoverished and wealthy citizens. The idea that politics is most successful where “mediocre” individuals are in power, clearly informed by Aristotle’s political philosophy, underscores the importance of prudence in the fair and equitable distribution of taxes and resources.

According to Morosini, knowledge of history provides rulers with practical advice for contemporary governance and enables better political decisions in the future. In this respect, Morosini’s description of prudence was in line with the definition provided by Cicero in De inventione and repeated by Albertanus of Brescia in Liber Consolationis et Consilii:

A prudent man will take care of his prudence in three ways: by arranging the present; by foreseeing the future; and by remembering the past, for […] he who does not provide for the future and does not provide for the present proves himself stupid.

The chapters concerning prudence refer both to the discourse on the equal distribution of resources and to the practical knowledge provided by history. Particularly, Morosini advocated for the principle of similarity and analogy between past events and present circumstances. Based on this principle, he developed a theory of the predictability of future historical events, which he saw as distinct from the predictability related to astronomy, where universal laws ensured the constant recurrence of events. For instance, alluding to the League of Cambrai, Morosini wrote that:

It has happened in the past that most empires have been suppressed, not so much by the force of the enemy, but by the support of neighboring countries that joined the enemy, while the insolence and importunity of the rulers perished.

Therefore, Morosini believed that the history of past “empires” demonstrated similarity to the present developments in the relations between the subjects of the Dominion and Venice’s enemies.

From the mid-fifteenth century onwards, prudence appeared in numerous Christian exegetical narratives and escape literature, including popular prayer books, where it was understood as the knowledge of when to flee from danger, with reference to biblical examples. Together with justice, fortitude, and temperance, they formed part of the four cardinal virtues: a system drawing from Catholic moral theology that permeated intellectual debates in Europe throughout the fifteenth century.

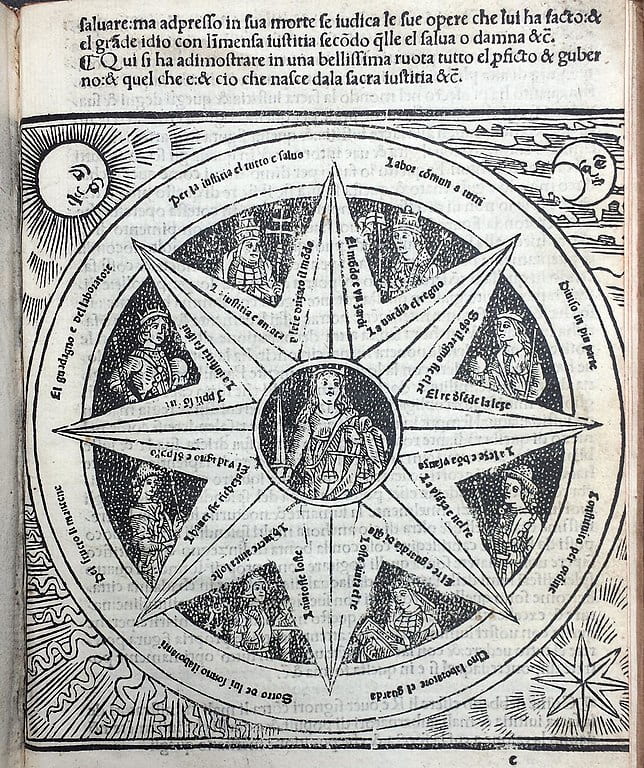

By combining the ideas of prudence with distributive justice, degli Allegri and Morosini contributed not only to the conceptualization of prudence and justice as pivotal virtues in Venetian politics but also to their dissociation from fortitude and temperance. Exemplifying this change, a woodcut in degli Allegri’s treatise depicted a “wheel of justice.” The depiction of the wheel contained—along its circle—sentences about the benefits of establishing equality in various areas of the administration of a state, from taxation to justice itself.

Within this new framework of political thought, Christian prudence was no longer identified as a simple remedy to fortune and potential dangers. Therefore, degli Allegri and Morosini fostered a new political understanding of prudence, which was no longer confined to religious thought: for instance, as it had been in the case of the Libro Devotissimo Chiamato Spechio de Prudentia, a book circulating in Venice in the early years of the sixteenth century.

Degli Allegri and Morosini fit into the humanist vision of prudence as virtue politics, in which prudence was indispensable to the successful governance of a republic. Thus, they greatly contributed to a crucial shift in sixteenth-century Venetian political thought, which aligned with anti-Machiavellian reaction against interpreting “prudence” solely in terms of self-interest and the personal strategy of the ruler.

Martina Calì is a PhD researcher in the Department of History at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy. She holds Master’s degrees in Philosophy and in Early Modern History from the University of Pisa, Italy. She has also carried out research and studies at the University of Heidelberg and the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence. Her doctoral research focuses on the narrative and rhetoric of prudentia in early modern Venice and analyzes treatises, archival documents, and images to identify the virtue of prudentia in Venice, considering the defeat at Agnadello as a turning point in the Venetian vision of this virtue.

Edited by Artur Banaszewski

Featured Image: Allegory of the victory over the League of Cambrai, circa 1590, Sala del Senato, Palazzo Ducale, Venice. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.