By David Kretz

On the face of it, art historian Andrei Pop, in his latest book, A Forest of Symbols: Art, Science and Truth in the Long Nineteenth Century (Zone Books, 2019), sets out to achieve something rather concrete—a reevaluation of the French symbolist movement in art—and yet the reader soon becomes aware that much more is at stake, as Pop weaves together art history with an account of early analytic philosophy to raise questions about the very nature of truth and human ways of meaning-making in artistic and scientific practice, which are further explored in this interview with David Kretz.

***

David Kretz (DK): A Forest of Symbols: Art, Science, and Truth in the Long Nineteenth Century begins by characterizing a type of mid-19th-century reductionism about the self and the mental that finds expression, for example, in Ernst Mach’s psychologistic philosophy and impressionist painting, which, roughly speaking, presents the viewer with sensations of color pigments rather than with objects. You then establish a surprising parallel between two counter-reactions to this Zeitgeist: symbolist art and early analytic philosophy, especially Frege and the Wittgenstein of the Tractatus. Can you sketch the parallel in their responses for us?

Andrei Pop (AP): The predominance of positivism and various forms of mechanistic philosophy and science, including physiological psychology, was no ideological conspiracy but a result of real progress: the invention of analytic chemistry, the refinement of celestial mechanics, and the rapid strides in comparative anatomy, microbiology, and the rest, crowned as we still think by Darwinian evolutionary theory. To say nothing of practical gains from pasteurization to electricity. This materialist front faltered a little when confronting the mind and subjectivity, but here too advances were legion: from the study of the eye and physiologic color to the psychology of counting and their manifold applications, from calculators to color printing, early motion pictures, and, yes, realist and impressionist painting. These art practices, of course, were not always understood as reductive, but insofar as they were—as they answered to the decree of “paint only what you see”—they fit the positivist lockstep.

Only they also produced weirdness: what an impressionist ‘saw’, made up as it was of blocky saturated brushstrokes, differed markedly from what anyone else saw, live or through a camera. So the act of translating vision to canvas produced an effect different in kind. At the same time, positivism was of little help in the foundations of arithmetic, or physics, where explaining natural law mechanistically and psychologically (a tendency called “psychologism” on the model of scientism—taking psychology beyond its field of application) led to theories of numbers as consensual hallucinations, or meaningless counters in a game. This self-undermining nature of positivism—its search for verification leading always to unstable mental states that could deceive the verifier—naturally led to revolt among ambitious scientists from Boltzmann to Cantor. The revolts tended to assert the reality of things unseen and strictly unseeable: whether infinite sets (Bolzano) or irrational numbers (Weierstrass) or both of these (Dedekind, Cantor, Frege). This is a reformed Platonism, because it doesn’t point us to the perfect Bed in the sky, but to what is necessary for there to be anything at all—the laws of arithmetic describe any possible universe. They certainly underlie the mathematical natural science on which positivism relied while undermining it.

It is perhaps surprising then that the scientific revolt against equating truth with the perceptible or verifiable, which issued in mathematical logic and philosophy of language that you call “early analytic philosophy”, also made room for domains inaccessible to it, what it called the subjective realm, which stretched from color perception and proprioception to poetic nuance to aesthetic judgment. If we identify the later tradition with the elimination of subjectivity and a nearly algorithmic commitment to the application of logic to philosophical problems, we may, ironically, regard Frege and the young Russell and Wittgenstein as backward Romantics, because they sought to delimit objective sense and laws from realms of radical subjectivity that separate each mind from each other: the very notion of private language, which the older Wittgenstein violently rejected. The philosophical point of this book is to show that the objective requires the subjective as a foil if it is to play the scientific role late nineteenth-century philosophers assigned to it, not to mention to become accessible through our perceptual apparatus in new kinds of mathematical and logical symbolism. As for the symbolist artists, they frankly acknowledged that the mind contributes as much as the hand in reproducing reality, so that continuous color and contour, which impressionism and the opticians had rejected as found nowhere in nature, reappear as signs of our subjective activity as perceivers as much as our logical activity organizing percepts into objects. The category of the image serves as a useful beacon, joining theoretical speculation to plastic art: it is structured sense itself, distinct from and mediating between the concrete things embodying it and whatever else, concrete or abstract, they stand for or refer to. But once one has noticed the affinity between the artistic and philosophical project, there is no reason to leave out photographers, realist painters, or romantic poets like Poe, when one finds them engaged in a project of exploring the interface between the logically objective, or public world, and the private, subjective worlds which Heraclitus already said we each possess.

DK: You agree with historians of science like Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison that there is an artistic aspect to scientific practices of observation and documentation, for example, but want to also claim the inverse: that artworks are, in a sense, truth-apt and logical. Truth in art, moreover, on your view lies not so much in its power to disclose a world (Heidegger, Gadamer). Rather your concept of truth in art seems to follow along representationalist lines: Frege and the early Wittgenstein. Could you tell us more about your understanding of truth—in art, in science? Are they the same? Is truth in art the same as meaningfulness?

AP: The opposition between disclosive and representationalist accounts of truth requires some scrutiny. I take it by the latter you have in mind the view that sentences or images build up models of reality, which we compare with their referent and judge to be true in case the representation corresponds to reality. Frege in fact denied that such a view is generally applicable to pictures—as he pointed out, we would only call a picture of Cologne Cathedral “true” in this sense if we appended the sentence “the cathedral looks like this”, so that what we are really judging true is the sentence. But then he went further and pointed out that the correspondence theory doesn’t explain truth in language either! For if you ask just what makes this sentence correspond to reality, and I provide an answer, you can still ask whether the answer is true, which on the correspondence theory would lead to asking for another object of correspondence (not of the sentence, but of the sentence asserting the truth of the sentence), and thus a vicious regress. So correspondence will not explain truth in general: but it certainly plays a role in much everyday language and imagery, from ID cards to IOUs.

So it won’t do to dismiss representation altogether and insist on elevated uses of “world-disclosing” language and images: it matters whether I owe you or you owe me a sum of money, just as it should matter to the disclosing of a peasant world whether, say, a pair of boots painted by Van Gogh belonged (are painted as belonging) to a peasant woman or not. What matters still has to do with the language or the image: these are logically articulated, which needn’t mean reducible to language. What it does mean is: properly interpreted, it is responsive to true or false propositions about it. This is how a picture differs from the object which is its bearer, as it differs from a stone or a leaf, which are neither meaningful nor potentially true or false, though we can say meaningful, true or false things about them. As for the worry that pictures allow for multiple plausible interpretations, that doesn’t differentiate them from language qualitatively, only quantitatively. A picture might seem awfully ambiguous about, say, the intentions of the person it portrays, but it is merely compatible with several different ones. In turn, a sentence describing a face, as Lessing noticed, is endlessly more ambiguous than even a crude visual image of that face. Logically articulated, then, in every domain, means something like this: the object would mean different things if it were structured otherwise.

Likewise, context matters: language abounds in indexical expressions whose full significance (as opposed to linguistic meaning) depends on who is speaking and listening, and the sense of images may depend on assumptions about who is looking, what goes on beyond the frame of the picture, and so on. This is why I like to say that a historian may not be a Platonist, but a Platonist must be a historian: you never reach mind-independent meaning from a historical artifact unless you account for specific human conventions and acts. As for truth, that is once again a further step: it is not objects as such, but the thoughts they provoke, which are true or false. The only guaranteed truths are the tautologies held in such suspicion by Wittgenstein—which are perfectly respectable logical truths, true solely due to their structure (the same goes for contradictions, which are necessarily false). As for other thoughts, their truth and falsity depends not so much on correspondence to fact (which, inconveniently, tends to ape the representational content of the thought), but on what they really mean. Again artifact and world, structure and context interlock, while remaining very much distinct.

And that is why images, and not just texts or scientific sentences, may be logically articulate: it’s because they are interesting, eventful. The Nelson Goodman line, according to which pictures are just analog color gradients with no structure, is as implausible as Heidegger’s speculations on peasant shoes, which he claims are accessible only in looking at a Van Gogh painting, but which in fact can only be had by reading Heidegger. In order for this kind of art theory to reestablish contact with ordinary acts of looking, and with communication between lookers, and their other intellectual activities (including science), logical structure has to be recognized wherever it is found. It is naturally rather unevenly distributed among meaningful artifacts (perspectival pictures may be dreadful at tense, but they are far better than sentences at describing spaces, and both are terrible at clarifying inferences). We also have to recognize and respect the incommunicable aspect of each subject’s experience, which we can sense rather than verify and which I suspect is what drives the world-disclosing philosophers to their premature attempts at disclosure.

DK: Is there anything that would make an artwork logically inarticulate? Would you rule out the possibility of interesting, eventful nonsense?

AP: I rule out “nonsense” understood as “no sense”, a degree zero of sense: the nonsense poems of Lear, Carroll, dada, medieval monks, etc. are in fact full of tidbits of sense, arranged less than sentence-wise (or even word-wise at times). So the “may be” above applies to the degree of coherence a particular artwork aspires to. A monochrome may well occupy a monistic logical space akin to David Chalmers’ fantastic “consciousness of a thermostat”. If so it is quite dull, perhaps inarticulate by our usual standards, but never unintelligible or senseless in a pure way. Poésie concrète, doodles, automatic writing are telic activities too, with a minimal sense that is requisite to being an interesting representation. Of course, a fossil or a blank wall may be interesting, but not as representation: only as a natural object about which questions may be asked.

DK: How does your understanding of these larger metaphysical and epistemological issues inflect your own methodology as a historian? What do you think art historians should learn from philosophy—and philosophers from (art) historians?

AP: I more than once heard a celebrated philosopher say that his only method is to never say anything that is obviously false. One could do worse! The use of external “theory” in art history once had a dogmatic cast—the writer “knows” that Marxism or Lacanian psychoanalysis or structural linguistics is right, and rearranges art, or rather the extant writings on it, in accordance with this certainty. The old (“classical”) Germanophone art historians by contrast had some philosophical training (generally neo-Kantian), which they did not flaunt, instead inventing terms like Kunstwollen (‘art-willing’), Pathosformel (‘pathos formula’) or symbolische Form (this one due to a philosopher, Ernst Cassirer) to do their philosophizing, still in a broad generalizing vein, but generally asserting a continuity or change over time in how concrete objects embodied these more abstract patterns or schemata. I hope I have learned some lessons from both traditions: to think on our feet when the form of artifacts is meaningful and to look outside them when artifacts reach into the world. Still, art historians must learn not just philosophical theories, but some habits of mind philosophers take for granted (notably analytic philosophers, whom too few of us read, but above all the great philosophical minds, wherever those occur): not to adopt any position because they think it’s right or will elicit admiration without understanding it, but to think for themselves, accepting only what on their best efforts they regard as the truth. This, of course, need not involve certainty, but includes possibilities and hypotheses and the most plausible conclusions.

Can philosophers in turn learn anything from art historians? Well, besides learning what not to do (in the bad case), most art history, and certainly art history at its best, abounds in careful and explicit observation of meaningful artifacts, from all known human cultures and epochs: I think it does so in a way that if properly taken up could challenge the philosophy of mind, of language (which really should be a branch of a larger philosophy of meaning), and of logic and science. Art history isn’t just interesting to aestheticians. Questions ranging from the compositionality of semantics to the nature of things can be elucidated, if not definitively answered, by closer attention to art and artifacts. Not that this will involve taking anything art historians say at face value, but most of what philosophers think about the limits of thought, discursive language and the expressible, would benefit from an acquaintance with a wider range of meaning-making tools. Knowing symbolic logic helps, but so do comics or sculpture or opera! I am just as bad, I have no clue what to make of key signatures and chord changes in music, which can be instruments of thought, as much as any syllogism or perspectival projection. The key to wisdom, I’d agree with Socrates, is knowing that we don’t know. That is something art historians and philosophers have in common with each other—and with everyone else.

Andrei Pop is a professor in the Committee on Social Thought and the Department of Art History at the University of Chicago. Previously, he has taught eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art history and aesthetics at the Universities of Basel and Vienna.

David Kretz is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Germanic Studies and the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. His current project contrasts poets and translators as complementary paradigms of historical agency in times of crisis.

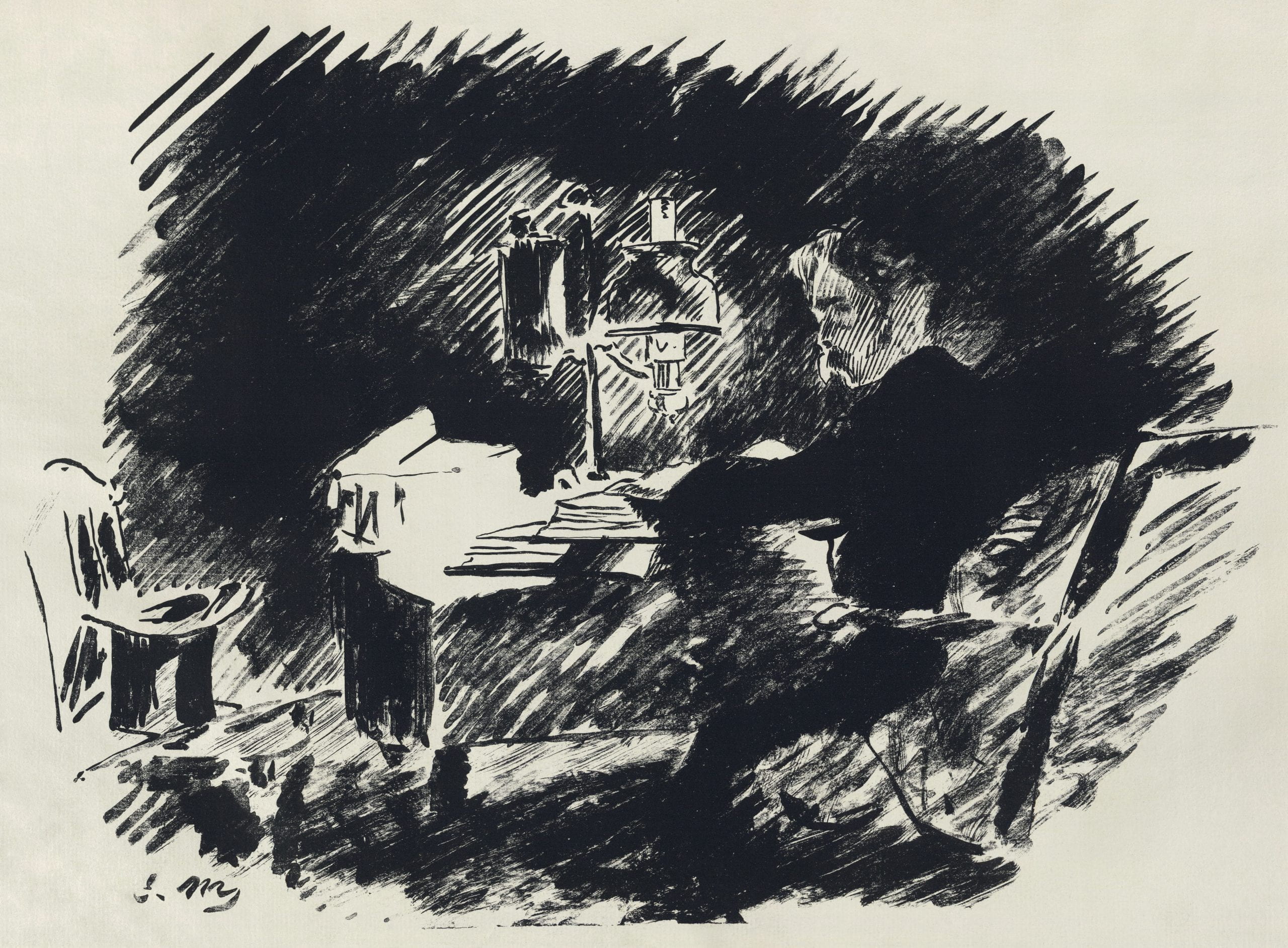

Featured Image: Édouard Manet, Illustration for Stéphane Mallarmé’s translation of “The Raven” by Edgar Allen Poe, 1875.