by Martina Garategaray

During the seventies and the eighties of the past century, Social Democracy, born and brewed in Europe, went beyond frontiers and settled in Latin America. As Bernd Rother and Fernando Pedrosa have argued, there was a mutual interest in these connections. On one hand, in the context of the Cold War and the bipolar world, Europe showed interest in what was happening in Latin America and the Caribbean with their struggle for democracy and human rights. Besides, the United States foreign policy towards Cuba and Vietnam, the support to the putsch against Allende in Chile, and the reactions to the events in Portugal in 1974 and 1975 convinced European social democrats that they had to become active in Latin America. On the other hand, Latin Americans rediscovered Social Democracy—in many cases due to the exile experience of intellectuals and politicians in Europe as a result of military dictatorships or because tightening ties with this tradition became an attractive option to break the United States hegemony in the region. In this context, two international actors became very active: the Friedrich Ebert Foundation (FES) and the Socialist International (SI) under Willy Brandt. Both institutions worked side by side in Latin America in elastic cooperation looking forward to break Eurocentrism.

After the end of World War II, the German Parliament passed a law of international cooperation that established that every political party with parliamentary representation would have a foundation to promote democracy worldwide which would be financed by the German state according to the size of the party’s bench. As many authors have pointed out, the law gave birth to the so-called German Political Foundations, making them an element of the German political system, with the particularity that although they are independent organizations, they are linked to the political philosophy of the great parties of that country.

The Friedrich Ebert Foundation—the largest and oldest of the German political foundations, linked to the Social Democratic Party (SPD) that was in the government coalition between 1969 and 1983, was launched in Latin America in the 1960s with the aim of building, deepening and promoting democratic systems in clear harmony with the ideals of Social Democracy. The first local offices opened in 1964 in Chile, 1965 in Costa Rica and 1969 in México, and soon spread throughout the region. In 1967, the central FES, located in Bonn, founded the Research Institute for Social Sciences, better known as the ILDIS, in Santiago de Chile. ILDIS was the first major project of the FES. In charge of the observation and analysis of the socio-political development in Chile and Latin America, it informed the Foundation on the needs of the region. After the military coup of Pinochet, they had to move their offices to Quito, Ecuador, where they are still working.

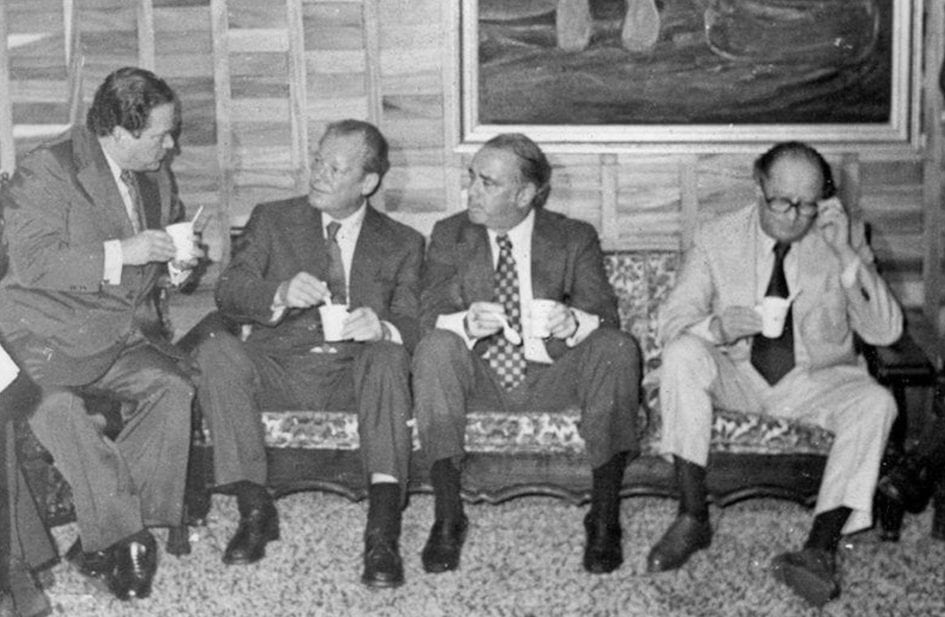

The second mayor project of the FES in the region was the establishment of an adult higher education institute, the Centre for Democratic Studies for Latin America (CEDAL), in Costa Rica. Luis Alberto Monge, leader of the National Liberation Party (PRD) of Costa Rica, a party traditionally linked to social democratic ideology, presented at the central FES a concrete plan for cooperation. Monge wanted to prevent Costa Rica from falling into the militarization of neighbouring countries and faced with the danger of communism, asked the FES for help. After several meetings between Monge and Günter Grunwald, director of the FES, the FES-CEDAL agreement was signed in 1968. CEDAL was born as the local executing agency of the education programs to be sponsored by the Ebert Foundation and until the 1990s, it provided political training courses, lectures, and seminars to a large number of future reformist political leaders.

In 1972, a third project was born, Nueva Sociedad (NUSO), a Latin American journal of social sciences which was initially published in San José, Costa Rica, moved to Caracas in 1976, and it has been published in Buenos Aires since 2005. The journal takes its name from Neue Gesellschaft, a publication of the SPD since the beginning of the twentieth century and was initially considered the Spanish version of Socialist Affairs, the Socialist International´s magazine. Ahead of all progressive ideas, and focused on the development of political, economic, and social democracy in the region, this magazine is an important bastion in the dissemination of social democratic ideas in Latin America.

Nonetheless, the interest of Social Democracy in Latin America was not new. In 1951, the Latin American Secretariat of the IS was established in Montevideo, Uruguay, under the coordination of Humberto Maiztegui. Even so, since mid-seventies its presence increased in the region under the leading figure of Willy Brandt, former German chancellor, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1971, president of the SI from 1976–1992 and an active FES member.

Held in Venezuela, under the Presidency of Carlos Andrés Pérez of Democratic Action (AD), the “[m]eeting of political leaders of Europe and America for International Democratic Solidarity”, better known as the “Conference of Caracas”, seemed as the official offensive of the International in Latin America and a novel starting point of the social democratic golden years. It was followed, not without tensions, with the creation in 1979 of the Socialist International Committee for Latin America and the Caribbean (SICLAC) under the Presidency of José Francisco Peña Gómez of the Dominican Revolutionary Party (PRD) of Dominican Republic.

Many political parties started to show interest in the International or became full members and many offices of the FES opened in the region in the context of military dictatorships, authoritarian rulers, and revolutionary uprisings. Conferences, seminars and dialogues, promoted by the Ebert Foundation, were important in connecting social democratic forces of Europe and Latina America on one side and, on the other, Latin American progressive tendencies among themselves.

In all of these spaces, the possibility of an autochthonous Social Democracy was discussed as a response to imperialism (always identified with the northern neighbour: the United States), to economic dependency showing the struggle of the Third World for a New Economic International Order, and to dictatorships and oppression. Latin American politicians and intellectuals found interest in the social democratic principles of liberty, justice, and solidarity, and in articulating them in the local context with other ideas such as equality, development, nation, and popular sectors, they were introduced into the regional debate.

Since 1976 until 1982, not only the ties between Europe and Latin America strengthened—many times badly addressed as exporting the German Model, finding new markets, or using Europeans money and influence—but also certain ideas and concepts circulated vigorously creating a community of thought between Europe and Latin America. Moreover, if concepts such as concertation, consensus or pluralism, that were not part of the Latin American political lexicon, started to be used, something similar happened with violence and revolution, almost condemned in the social democratic tradition or nationalism and populism, with a controversial history in Germany that associated them with the Nazi experience.

The local context (with its dictatorships, military interventions, popular uprising and revolutions as the Sandinista one) was receptive to social democratic ideas and socialist leaders were sensitive to what was happening in the region. Willy Brandt was especially empathic with the situation in Nicaragua during the late seventies and early eighties justifying revolutionary violence and was one of the promoters of ideological flexibility.

International actors, such as the FES and the IS, intervened in the construction of a language of democracy by supporting democratic and popular leaders and helping to undermine dictatorial regimes, and this can be apprehended in the circulation and exchange of ideas. Therefore, I argue, since mid-seventies until mid-eighties, the circulation of social democratic ideas in Latin America was intense and consisted of a double movement of reception and re-signification; if Social Democracy had become trans-national since the seventies, it was re-signified in Latin American latitudes through this period. If the Malvinas struggle was a delicate episode in the relation—while Latin Americans supported the Argentinian claim of sovereignty, Europeans refused to back a dictatorial invasion—it represented a stop but not the end of the relation.

The circulation of Social Democratic topics in Latin America defined a new argumentative plot, and in this new plot many concepts were transformed and re-conceptualized in Latin America as well as in Germany. On the German side, in thinking the particularities of Latin America, as I pointed out, the appreciations of nationalism, populism, violence and revolution changed as dogmatism let its way to pragmatism and political flexibility. On the Latin American side, leftist traditions that were critical of democracy and human rights started a re-valorization of them.

In overcoming eurocentrism, Social Democracy trans-nationalized, with its particularities. Nevertheless, by 1992, after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany, the interest decreased. Germans were more worried about internal politics rather than external ones; Willy Brandt, who passed away that very year, was no longer around to promote alliances; and the bright future imagined in the Caracas Conference of 1976 faded away. On the Latin American side, the interest in Social Democracy also decreased with the rise of neoliberal ideas, the emergence of serious economic crisis (some of them during governments that had embraced Social Democracy) and right-wing governments. National and international conditions had changed, and the new context demanded new ideas. Social democracy´s golden years came to an end, but we can argue that many of the conceptual debates of those years still persist in contemporary democratic disputes.

Martina Garategaray holds a PhD in Social Sciences from the University of Buenos Aires, a Master’s degree in History from the Torcuato Di Tella University and a BA in Political Science from the University of Buenos Aires (UBA). Since 2009 she is a member of the Centre for Intellectual History at the University of Quilmes (UNQ) where she is the Director of the research line: “Political languages in Latin America in the second half of the 20th century.” And since 2020 she has been an Adjunct Researcher at CONICET. Martina obtained grants and has been a visiting researcher at Stanford University (2013), at the Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut (IAI) (2014, 2021-2022), and at the Lateinamerika-Institut (LAI) of the Freie Universität Berlin (2021-2022). Since 2003 she has been a university lecturer in undergraduate and postgraduate courses at the UBA and the UNQ. She has participated in numerous national and international conferences and her publications include the books Unidos, la revista peronista de los ochenta (2018) and co-authored with Ariana Reano La transición democrática como contexto intelectual. Debates políticos en la Argentina de los años ochenta (2021) among other articles and book chapters.

Edited by Pablo Martínez Gramuglia

Featured image: Left to right: Luis Alberto Monge, Willy Brandt, Daniel Oduber, Bruno Kreisky. Courtesy of Centro de Estudios Democráticos de América Latina, Creative Commons, www.cedal.org.