by Daniel Judt

In the winter of 1891, a young John Dewey published an article in a student newspaper at the University of Michigan, where he had just begun to teach. The article, a response to what Dewey felt was a regrettable trend toward obscurantism in philosophers’ writings about truth, was titled “The Scholastic and the Speculator.” Dewey proposed a division between two ways of knowing what is true. The first way was to find a real quality of the world—a fact, or equally a moral principle—and pluck it from its context to lend it an air of universality. This was the “Scholastic’s” method. It involved “taking a thing out of relations and keeping it out” (151). “Not to put too fine a point on it,” Dewey continued, but “the Scholastic was an embezzler.” He “sav[ed] and stor[ed]” without ever giving back. Yet “this abstraction, this saving cannot be all there is to the matter,” Dewey insisted. “These must have some end, some use. What is it?” (152).

The answer came with the second way of getting at truth. “Intelligence must throw its fund out again into the stress of life,” wrote Dewey. “It must venture its savings against the pressure of facts” (152). This was the method of the Speculator, whose procedures Dewey elaborated with an extended economic metaphor:

Every judgment a man passes on life is perforce, his ‘I bet,’ his speculation. So much of his saved capital of truth he invests in the judgment: ‘The state of things is thus and so.’ The current of fact sweeps in this judgment and returns it to him with interest. His guess, his venture has won: the logicians call it verification. Or the stream of fact carries away his investment and he never sees it again. His speculation was against the set of the market and he has lost. (154)

Dewey’s economy of truth was financial. Truths were never fixed. They were contingent social creations that gained (or lost) their value over time and through their reception in the ever-changing “stream of fact.” This fluctuation of value and the uncertainty it generated were inevitable—and, what is more intriguing, they were necessary for the generation and discovery of future truths. The speculator did not know if his beliefs would make it out there in the world. Without that risk, the entire process of speculation would make no sense. Uncertainty was a happy precondition of those investments, those wagers, which brought new truths into being.

And yet if Dewey’s metaphor nodded to the productive capacities of finance, it also struck a note of caution. Healthy speculation had its limits. “There is a speculation which exists just for the sake of the speculation,” Dewey cautioned (154). The key was to remain an investor who stakes his individual funds for a social end. This, Dewey concluded, was the proper kind of truth-seeker: one who “both saves and spends, yet neither embezzles nor gambles” (154). To a striking degree, Dewey’s vision presages the model form of investment that John Maynard Keynes would lay out many decades later in his General Theory. For capitalism to work, Keynes argued, capitalists must not speculate wildly and must not hoard their money under the bed—two forms of equally destructive liquidity fetish. Instead, they must use their liquidity toward long-term, productive investments. As with capital for Keynes, so with truth for Dewey.

*

The idea that pragmatism has a strong connection to capitalism has been around almost as long as pragmatism itself. (Dewey wasn’t alone in using economic metaphors; William James famously wrote that truth functions like a “credit economy.”) But the terms of this connection remain vague. Critics have decried what Lewis Mumford, in 1926, called pragmatism’s “acquiescence” to capitalist society. Defenders of pragmatism have dismissed the question entirely, focusing instead on pragmatism’s construction of what the philosopher Hillary Putnam called an “epistemological justification of democracy.” A rare exception to this tiresome dichotomy is the work of James Livingston, which urges us to take pragmatism’s dalliances with economic language not as “an apology for modern capitalism,” but rather an effort “to explain how truth works in our time.”

Livingston is right. What is striking about the above passage is not that it proves Dewey’s affinity for capitalism. It invites us to think about pragmatism’s theory of truth as a reflection of the process of capital. The latter is an historical phenomenon, transitioning through distinct phases over the past century and a half. What would it mean to map pragmatism’s theory of truth onto those shifting logics of capital across the Twentieth Century? What follows is a highly speculative story, in Deweyan fashion, to get us talking about that question.

Dewey’s “speculator” theory becomes sensible when set against the backdrop of debates over money and value that seized Americans’ political consciousness in the period between the Civil War and the early Progressive Era. The “money question”—whether America should maintain a fluctuating fiat currency or return to a “hard money” economy pegged to rare metals—pointed to a world in which, as one hard-money pamphlet from the 1870s fearfully warned, “value is not fixed.” The explosion of futures contracts in the 1880s, dealing in what skeptics warily regarded as “fictitious commodities,” reinforced this sensation of unmoored values. A few years later, the Great Merger Movement saw firms recapitalize using a new system of valuation based on expected future returns (and not current productive capital). These upheavals accompanied the rise of American finance capital to hitherto unseen influence at home and abroad.

They also signaled a fundamental shift in political economy. Capital came of age, in the historian Jonathan Levy’s words, as “the process through which a legal asset is invested with pecuniary value in light of its capacity to yield a future pecuniary profit.” Thinking of capital in this way shifts the burden of value-generation away from the accumulation of past labor and toward what sociologist Jens Beckert has called “imagined futures,” which implies an epistemological worldview that emphasizes uncertainty, futurity, and speculation. “That is perhaps capitalism’s greatest transformation,” Levy concludes: “to order present economic action toward an uncertain future, as opposed to the mere replication of the economic past.”

When Dewey wrote of speculation and investment as the key to a process of truth-seeking, he adopted this newly prevalent economic logic. We might even say that pragmatism’s “greatest transformation,” especially in Dewey’s formulations, mirrored capitalism’s. (Other influences were also at play, of course: Darwinism and civic humanism, to name just two.) It ordered present conclusions about truth, value, and action “toward an uncertain future,” as opposed to the mere summation of what we understood to be true, valuable, or a proper course of action based on past experience.

How, then, could values and truths become fixed and stable? Who got to speculate? These questions ran through American politics in the Progressive Era. Whether the call was for an “industrial democracy” or an “investor’s democracy,” the tension remained the same: how could the propulsive, future-oriented, destabilizing process of capital be stabilized and democratized? Perhaps this is where pragmatism’s engagement with capitalism intersects its argument for democracy. Dewey’s middle and later writings moved away from economic metaphors. But he continued to work through the same questions about how to settle truth without foundations. For instance, in Individualism Old and New (1930):

No scientific inquirer can keep what he finds to himself or turn it to merely private account without losing his scientific standing. Everything discovered belongs to the community of workers. Every new idea and theory has to be submitted to this community for confirmation and test. There is an expanding community of cooperative effort and of truth. (154)

This is quintessential Dewey—the emphasis on scientific inquiry as a model for truth-seeking, the vague hint of producerism in the claim of worker-ownership, and the expansion of this model of “cooperative effort” to a democratic theory of knowledge production and social order. But it also appears to be a re-articulation of the ideal speculator, always investing his capital (his truths) out into the community so that they might aid social growth. (In the same chapter, Dewey went on to argue that those who “turn their backs upon” the “existing economic order” are just as responsible for its depravities as those who “employ [it] for selfish pecuniary gain” (158)—another echo of his argument about the wanton speculator and the hoarding scholastic serving the same negative social role.) Perhaps Deweyan pragmatism’s shift to a focus on the democratic nature of truth-seeking can be read as an effort to answer the political question posed by its own theory of truth—who sets value, and on what grounds?—which was, by extension, the question posed by the prevailing logics of capital.

Historians tend to argue that pragmatism was “eclipsed” from the mid-1940s through the mid-1970s. Hobbled by attacks from critics in the 1920s, the narrative goes, pragmatism collapsed under the combined weight of prolonged economic crisis, world war, and anti-communism, all of which seemed to demand a re-grounding of morals and politics in metaphysical values. Yet recent scholarship on pragmatism at midcentury has troubled this narrative. Pragmatism was not “eclipsed” so much as it became ubiquitous, entering the intellectual bloodstream in a wide range of fields, from analytic philosophy to the human sciences to government administration. It is not coincidental that many of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famed advisors and policymakers, from Rexford Tugwell to Alvin Hansen to Robert Wagner—the architects of what we know as the “New Deal Order”—were either educated by or worked alongside committed pragmatists in the Progressive Era.

Could we supplement this emerging narrative of classical pragmatism’s quiet blossoming at midcentury with one that continues the story I have been sketching—pragmatism as a philosophical response to the logics of capital? Historians such as Jonathan Levy, Amy Offner, and Brent Cebul (all from quite different angles) have begun to write about the New Deal Order as a thirty-year American effort to cajole capital into long-term, illiquid investments in national industry: that is, to make it fixed and settled rather than fluctuating and speculative. Could the midcentury ubiquity of pragmatism—a ubiquity that almost made it seem superfluous—also have roots in the temporary success of this new form of regulated capitalism, which sought to realize harnessing the process of capital without halting it? If this is right, then Dewey’s ideal speculator was perhaps a metaphor before its time, less suited for the unstable speculative frenzies of the early century than for the Keynesian “Age of Control” that followed.

But that midcentury moment did not last. Nixon took the U.S. off the gold standard for good in 1973. State controls on capital were dismantled and then replaced by risk-hedging financial products. The country lurched into a socioeconomic moment that we still have trouble labeling: neoliberalism, “post-industrialist,” the “asset economy”? But even if the name is not settled, recent scholarship has helped to clarify that post-postwar capitalism was (or still is) marked by a surge in speculative, short-term investments and a decline in illiquid, long-term ones. This “high degree of liquidity preference” certainly bears some resemblance to the political economy of the Gilded Age and early Progressive Era. A key difference, though, is that this time around there would be no coming industrial wave that could anchor speculation to the material world, but instead a service economy to buttress financial growth—unless, of course, Joe Biden’s “New Industrial Policy” and a dose of military Keynesianism somehow upends this. An economy of things gave way, to a degree heretofore unseen, to an economy of (speculative) thoughts.

Might there be a connection between this third and final logic of capital in the twentieth century and the rise of neo-pragmatism? The latter, especially as articulated by the philosopher Richard Rorty, rewrote classical pragmatism for the age of the “linguistic turn.” Its theory of truth puts little, if any stock, in “experience.” The relevant interaction was people talking to each other, experimenting with new “vocabularies” and “redescriptions”—not reaching out into the physical world, since material objects had no set meaning, no value, beyond what we gave to them. In the terms that Dewey laid out in his article, neo-pragmatists were an unhealthy kind of speculator. In their embrace of speculation without verification, they advanced a theory of truth that mirrors our moment’s hot-money, liquidity-fetishizing, fast-and-loose economy. The Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson famously described postmodernism as “the cultural logic of late capitalism.” Could neo-pragmatism be its philosophical accompaniment?

*

If this story held up under scrutiny, it would imply that the twentieth-century history of American capitalism and the history of American pragmatism are of a kind. Both can be mapped onto the process that Dewey laid out in his “Scholastic and Speculator” article: the effort to strike a balance between uncertainty and stability, speculation and investment. That such a balance was struck at midcentury (though never with the accompanying democratic control that Dewey envisioned) is significant for our understanding of pragmatism and capitalism. But that the balance proved fleeting is equally telling. When Dewey proposed a theory of truth as financial speculation, he was beginning to poke at what the pragmatist philosopher Colin Koopman has recently called “the most crucial philosophical problematic of our times: namely, the task … articulating normativity without foundations.” This problematic, premised as it is on the inevitability of uncertainty and the need for stability, is a tension posed by capital that pragmatism has tried, and I fear failed, to resolve.

Daniel Judt is a PhD student in modern US history at Yale University. His research focuses on the relationship between labor struggles and leftist political thought in twentieth-century America.

Edited by Thomas Furse

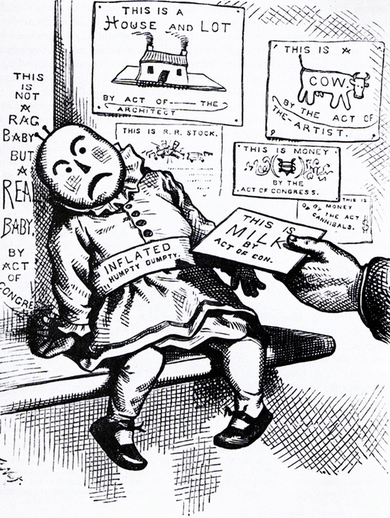

Featured image: Thomas Nast, “Milk Tickets for Babies,” in David Ames Wells, Robinson Crusoe’s Money (1876).