By Jacomien Prins

In current debates on music and emotion a thorny issue arises time and again: how should we deal with negative emotions in music and with negative responses to music? It is relatively easy to interpret tears as an expression of sadness in a person. In fact, we usually believe that only sentient beings can express emotions. Given that works of music are not sentient, emotions cannot be expressed in them. However, many scholars have recently begun to show renewed interest in organicist cosmology, in which objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Similarly, in Western musical culture, it is quite common to believe that music can express emotions such as sadness or happiness. If we accept that music can express a negative emotion such as sadness and that music can communicate this emotion to the listener, another problem emerges. In general, we tend to avoid sad experiences. But at the same time, many people are attracted to sad music, which can induce a negative emotional response in the listener, such as sadness.

How can we explain this? Many explanations have been given, among them explanations in terms of the Aristotelian doctrine of catharsis, according to which it is beneficial for humans to purge their negative emotions by experiencing art. According to this type of theory, the aesthetic context would provide a safe context to experience negative emotions without the problems and dangers with which humans are confronted in the real world. This approach is not new. In the seventeenth century, the polymath and music theorist Marin Mersenne (1588–1648) already presented the doctrine of catharsis as part of an innovative theory about music and emotion (see Fig. 1).

In his Harmonie universelle (1636), as part of an investigation into the connection between music and the passions of the soul, i.e., the emotions, Mersenne examined the paradoxical experience that “songs one calls sad and languid are often more agreeable and sweet than those called gay.” He argued that the question was not useless, for “if it is well explained it will make us know the nature of man or of music.” It was generally believed that cheerful songs were more agreeable than sad ones, because all humans wanted to enjoy themselves and flee from sadness, which ruins their health. Mersenne used the fact that sad songs could lead to joy to prove them wrong by demonstrating that certain emotions induced by sad music could have a positive effect on a human being, leading to a greater acceptance of the human condition and to lasting happiness.

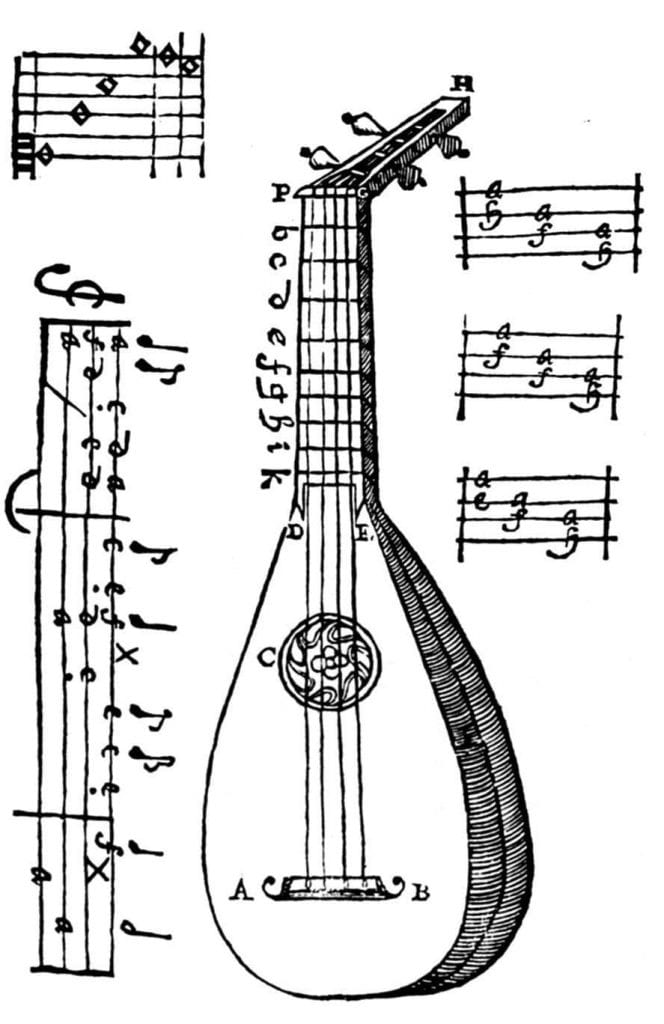

In seventeenth-century France, it was common knowledge that ballet tunes with their swift movements and high sounds were more exhilarating than the tunes played on the lute or the bass viol with their slow movements and low sounds (see Fig. 2). Cheerful music was seen as life-affirming because it had a positive effect on the heartbeat as well as an uplifting effect on someone’s mood. But many musicians and educated listeners in Mersenne’s circle were of the opposite opinion and asserted that they derived more pleasure from sad songs than from merry ones. Mersenne was very fond of sad songs such as Me veux tu voir mourir (Would you like to see me die), which around 1640 became the subject of a competition between the composers Antoine Boësset and Johan Albert Ban (see Music Example 1 and Music Example 2). Mersenne, who played a central role in European intellectual life of the first half of the seventeenth century, organized the musical performances at the French court himself.

One possible explanation for this could be that a human being has much more of the humor melancholy in his blood than the humor bile. This view was based on the Galenic doctrine of the humors and temperaments, according to which a healthy person enjoys a balance of the four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, or choler and black bile). Furthermore, excess of blood produces a sanguine, phlegm a phlegmatic, yellow bile a choleric, and black bile a melancholic temperament. In seventeenth-century theories of music and the affections, music was seen as a powerful instrument to influence the pulse, and with that also the humors and temperaments. Because humans are, in Mersenne’s view, more attached to the earth with which melancholy is associated than to the air or to the heavens, sad music is more similar to their nature than cheerful music. But since all kinds of musicians and listeners, whether bilious or melancholic humans, like sad songs better than merry ones, Mersenne argued that it would be better to look for an explanation in the nature of sad music itself rather than in the temperament of the listener.

Before dealing with the sad nature of music, Mersenne discussed human responses to tragedies. If one looked at the way people were attracted to tragedies, Mersenne wrote, one could see that they were inclined to compassion more than to enjoyment. He continued his explanation of the uplifting effects of sad music with his view on human nature (translation by Ruth Katz and Carl Dahlhaus):

But it must be noted that all men are more subject to sadness than to joy; for if everybody were to reflect upon his past actions or on the thoughts he has when he is alone, he would find ten sad ones for one happy one: for sadness is our lot since the Original Sin is quasinatural to us, whilst we meet joy by accident, as happens in merry company where everyone makes an effort to make his companions happy, which does not often succeed, and who laughs with his mouth has sadness in his heart.

Although cultural conventions prevented human beings from expressing their emotions freely, Mersenne argued that behind this façade, all humans shared the same universal emotions. But while it is relatively easy to understand how humans express or hide their emotions, it is more difficult to attribute emotions to music. As a first step towards a solution, Mersenne suggests that tunes of lamentation represent or imitate the movements of sadness in a human voice. A descending chromatic line played slowly and softly, for example, portrays the great sadness of a sinking heart, while two descending chromatic notes express a tearful sigh (a ‘Seufzer’). Music therapy in the Renaissance was based on the doctrine of Hippocrates, who argued that opposites are cured by their opposites (allopathy), which means that melancholy or depression could be cured by cheerful music. However, Mersenne based his view on the healing power of music on Paracelsus, who believed that likes are cured by their likes (homoeopathy), which implies that sadness could be cured by sad music.

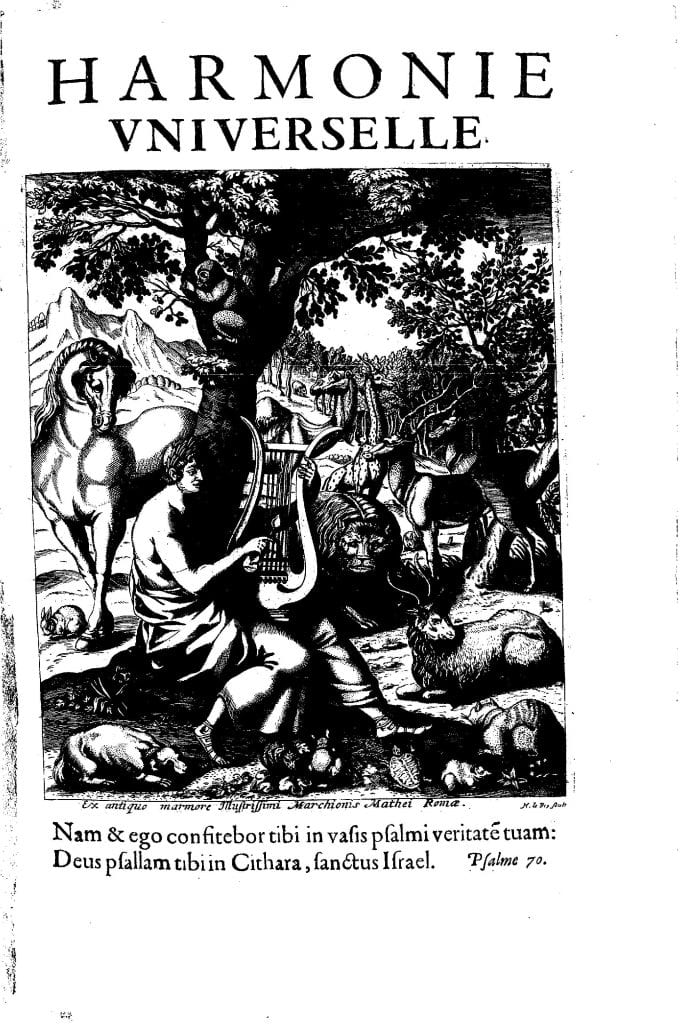

Mersenne argued with Aristotle that both songs with a sad and tragic text and instrumental music in which sad emotions were imitated could move humans to compassion – as if they were participating in the misfortune of the protagonists. This is because humans can imagine falling victim to a similar predicament and experiencing similar emotions. Moreover, Mersenne used the biblical story of David and Saul to demonstrate that sad music could ultimately bring consolation (see Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). In the famous biblical scene, David cured Saul from his depression by playing the harp (1 Samuel 16:23): “And it came to pass, when the evil spirit from God was upon Saul, that David took an harp, and played with his hand: so Saul was refreshed, and was well, and the evil spirit departed from him.”

Relying both on well-known stories and on his own musical experience, Mersenne defined sad music as the most powerful kind, with the greatest effect on the emotions. Because sad music could transcend normal embodied experience, it had an enormous power to influence the soul, which could thereby be directed to the “road leading to wisdom” (translation modified from Ruth Katz and Carl Dahlhaus):

[…] it must be noted that music, in a certain manner, separates the soul from the body and transports it into a state in which it is more suited to contemplation than to action, and consequently, when the song has ended, it [the soul] is quite astonished to find itself deprived of the great contentment which it had derived from the state of abstraction into which the music had transported it. […] And one could say that the deep melancholy, into which the soul falls in the presence of chant of lament, is not a sadness in the proper sense, but rather a road leading to wisdom, to which melancholy is more conducive than joy which approaches folly and which even more impairs the reasoning and functioning of the soul, which is the greatest.

According to Mersenne, no one liked sadness, but most listeners enjoyed an ecstatic musical experience. In his view, listening to sad music was a kind of meditative practice, in which one could make contact with one’s deepest self. Such a musical experience could not only bring a kind of consolation which words could not express but could even lead to true wisdom and compassion. In Mersenne’s quotation, the positive effects of sad music as a deep and lasting delight is contrasted with the superficial, passing pleasures of merry music, which is seen as a kind of distraction from getting to know yourself and your deepest emotions. Listening to sad music can also teach humans important virtues, such as resilience and peace of mind, which played a vital role in Renaissance philosophy. During the Renaissance, the ancient idea of music’s ethical power to affect man’s soul was revived. Ethical powers were assigned to modes and tonalities and the melodies shaped from them, though such specific combinations of musical modes and emotions were rarely offered in ancient accounts of the doctrine of the power of music.

Ultimately, Mersenne was convinced that since all human creatures possessed the same reason and the same emotions, music could function as a universal language that all people could use to communicate and to induce moral improvement in themselves and their fellow human beings. Interestingly, Mersenne argued here against the tradition that the most essential and significant elements of human’s musical experience are in their emotions and not in their reason. The latter view was a cornerstone of the humanist tradition, in which the meaning of the words in a vocal composition were seen as the most valuable aspect of music. In sharp contrast, Mersenne argued that the ineffable meaning of the musical material itself was more important than the meaning of the text. In this regard, he was one of the founders of the doctrine of music as language of the soul, which became one of the pillars of Western musical aesthetics and music therapy.

Where many contemporary scholars have difficulties in explaining why many people enjoy listening to music in which negative emotions such as sadness are presented, which can lead to similar emotional responses in the listener, Mersenne’s views on music and emotion can demonstrate that interpretations of negative emotions are not universal: at different moments in time, they have been reconstructed differently, according to dominant values, norms, and systems of knowledge. Therefore, his thoughts can refine our conceptions of the problem.

To formulate an answer to the problem, Mersenne took the human condition („for sadness is our lot since the Original Sin and is quasi natural to us“, quoted above in the text) as a point of departure and argued that most people would never try to avoid all negative aspects of life, simply because this would be impossible. Accordingly, he classified sad music and emotions of melancholy among the valuable and positive aspects of life. In Mersenne’s view, sadness is a part of being human and should not only be endured but also embraced, for example by listening to sad music. Such a musical experience could not only teach us important values, such as compassion, wisdom, resilience, and peace of mind, but also offer us consolation in difficult times. Mersenne was fascinated by the fact that the human soul is attuned to both the mathematical structure of music and the linguistic structure of language. In contrast to Descartes, who believed that music could only induce superficial sensual pleasure, Mersenne defended the opposite view, that music can express both the structure of the universe and the deepest layers of the human soul.

Mersenne associated the experience of listening to sad music with the emotions of faith, hope and love, considering it an important tool to discover the deeper meaning of life. In line with important philosophical and religious traditions, Mersenne thought that to achieve a fulfilling life, a person should embrace all its positive and negative dimensions. Mersenne’s view should be seen as a valuable alternative to more hedonistic interpretations of music and emotion, which assume that music is primarily meant to increase pleasure and happiness by decreasing pain and sadness in a more straightforward way. Mersenne was right that listening to sad music is an experience that can give insights into associated positive emotions of a lasting peace of mind and delight in a responsive listener.

I would like to thank Philippe Schmid, who asked me to contribute to the JHI Blog, for his constructive feedback on my essay. If not stated otherwise, all translations are my own.

Jacomien Prins is a Research Fellow at Utrecht University, with a particular interest in the history of music and philosophy. She is the author of Echoes of an Invisible World: Marsilio Ficino and Francesco Patrizi on Cosmic Order and Music Theory(Brill, 2014) and co-editor of Sing Aloud Harmonious Spheres: Renaissance Conceptions of Cosmic Harmony(Routledge, 2017) and The Routledge Companion to Music, Mind, and Well-being (Routledge, 2018). Her new monograph, A Well-Tempered Life: Music, Health, and Happiness in Renaissance Learning, in which Marin Mersenne plays a prominent role, is forthcoming.

Edited by Philippe Schmid

Featured Image: Réunion de musiciens. Painting by François Puget (1651–1707); oil on canvas, 1688. Département des Peintures, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Courtesy of Musée du Louvre.