By Cynthia Houng

Charlotta Forss is a Postdoctoral Researcher at Stockholm University’s Historiska Institutionen. Forss’s article, “Mapping Atlantis: Olof Rudbeck and the Use of Maps in Early Modern Scholarship,” published in the April 2023 issue of the Journal of the History of Ideas, explores the role of maps in Rudbeck’s practices of knowledge making and scholarship.

Contributing editor Cynthia Houng interviewed Forss about how Rudbeck came to possess the expertise necessary to make and use maps, her current research on the history of saunas in Sweden, and her forthcoming book, Mapping the Idea of North.

Cynthia Houng: Let’s start with an easy question. Tell us about the beginnings of this project—how did you become interested in writing on Olof Rudbeck and his use of maps?

Charlotta Forss: I stumbled upon Rudbeck’s copy of Taflor, his compendium of maps and prints, at the Royal Library in Stockholm as I was working on another project. Rudbeck has made extensive emendations and commentary all over the maps, chronological tables, city plans, and prints of antiquities in Taflor. Ever since leafing through his book, which is enigmatic in its own right even without Rudbeck’s additions, I have been puzzling over early modern note taking on maps, looking for an opportunity to delve deeper into the ways Rudbeck’s work with maps shaped his research.

CH: Did Rudbeck continue working on medicine and anatomy after he began work on the Atlantica project in the 1670s? Do you see any traces of influence or cross pollination between Rudbeck’s interest in medicine and anatomy and his interest in history and geography?

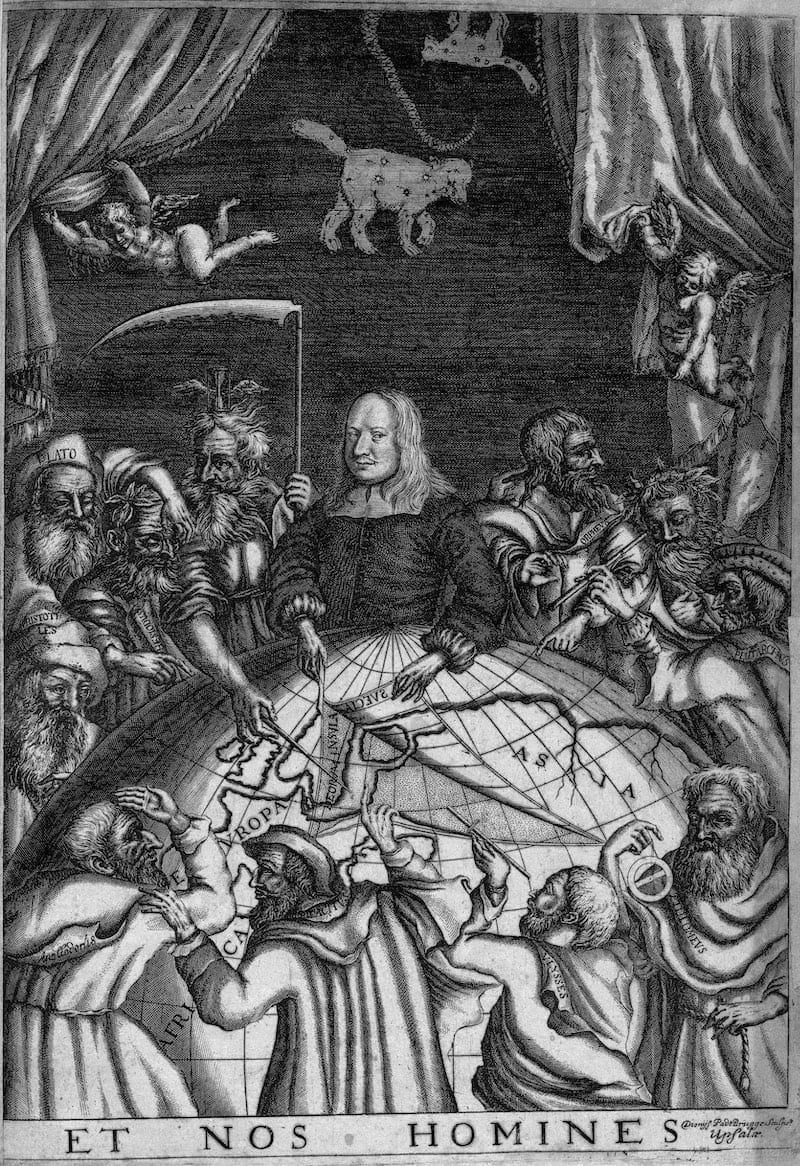

CF: Rudbeck’s background in medicine can be seen through his language use and the way in which he conceptualized world geography as akin to anatomy. A striking example of this is the famous frontispiece of the Atlantica (reproduced in my article) where Rudbeck has depicted himself performing a sort of vivisection on the earth, peeling back the surface of the northern hemisphere to examine the historical geography that would prove to him that Sweden was the sunken continent Atlantis.

Though Rudbeck did not continue to pursue active medical research once the Atlantica began to take up more and more of his time, he did continue to hold a chair as professor of medicine at Uppsala University until 1691 (when he ceded the post to his son, Olof Rudbeck the Younger). He also had several side projects that related to medicine. For example, he began planting the first botanical garden in Sweden in 1655. Throughout his career, he taught students “in the garden” about the properties, medical and otherwise, of his large collection of plants.

CH: It is fascinating to see how Rudbeck’s interest in geography and in spatial ways of thinking influenced other aspects of his work. Botanical gardens are such an interesting way to spatialize botany and unfold botanical knowledge in space. Tangentially: North American readers interested in botany will recognize the Rudbeck name. Many familiar North American wildflowers–such as coneflowers and black-eyed Susans–belong to the genus Rudbeckia. Linnaeus chose this name to honor the Rudbecks for their contributions to botany.

CF: I agree, the botanical project is absolutely fascinating in its own right. This is also one among many instances where Rudbeck and his ideas figure in the background of later scientific developments. Linneaus was a student of Olof Rudbeck the Younger in Uppsala, who himself continued to develop the ideas first proposed in the Atlantica. It is a tantalizing example of scholarly generations.

CH: Your paper is largely concerned with how scholars used maps to construct knowledge, but I’d like to detour and ask, how did Rudbeck come to possess his expertise regarding maps and mapmaking? How did Rudbeck learn to draw? How did he acquire the skills to make maps? How did he develop his skills as a draftsman and cartographer?

CF: This is a question I have been thinking about quite a lot. There is plenty that we do not know about Rudbeck’s early life and education, but it is still possible to draw some conclusions both about Rudbeck’s experiences, and more generally about “geography” education in seventeenth-century Sweden, before the formulation of modern scientific disciplines. The latter is also a topic I addressed in my doctoral thesis, “The Old, the New and the Unknown: The Continents and the Making of Geographical Knowledge in Seventeenth-Century Sweden.”

To begin with, it is likely that Rudbeck got some of his interest for inventive geographical presentation already at home. His father Johannes Rudbeckius was a professor of mathematics in Uppsala and later bishop in Västerås, in central Sweden, where he also founded the first gymnasium in the country. Johannes Rudbeckius made two world maps and several chorographic maps, all of which are oriented with south at the top of the map. This was a time period when geographic conventions, that we often take for granted, were not yet fully established; yet, Rudbeckius (or perhaps his publisher) still felt the need to comment on the design of one of the world maps that “One should not be surprised that this map is placed [in a way] that differs from common practice, since it is structured so as to show the situation of the world and specific places from the vantage point of us, the people in the North.” I would like to think that it was formative for Rudbeck to have a father who was both knowledgeable in mapmaking, keen to emphasize a northern worldview, and open to the idea that geographical presentations could vary in creative ways.

On a more general level, students were taught the basic elements of world geography in school as well as at university. This teaching happened both through lectures, and through instruction around maps and globes. Some of this education was tied to history and politics, where students were supposed to use geographical and chronological knowledge as “the two eyes of history,” helping them elucidate what had happened and where. Related to this, much of the education on geographical knowledge was tied to religious instruction. For example, knowing the ancient place names of modern localities could aid students in understanding events in the Bible. Finally, geography was also taught as part of mathematics. This included both descriptive geography and instruction about how to read and make maps. Outside of the university, and from the 1620s onwards, education in practical surveying techniques was organized through the newly instated Land Survey Office. The early modern Swedish state invested a good deal of manpower and resources into the mapping of the realm.

Rudbeck was a student at Uppsala University, and he also spent time in Leiden as part of his educational training and research. His biographer Gunnar Eriksson has noted that the time in Leiden was particularly important for Rudbeck’s later work on technical instruments (see The Atlantic Vision: Olaus Rudbeck and Baroque Science (Canton, MA: Science History Publications, 1994). Perhaps Rudbeck also received instruction in mapmaking in Leiden? Regardless, he was considered to be a proficient mapmaker back home, receiving commissions from friends and acquaintances to make various maps.

CH: In your article, you discuss Rudbeck’s processes of annotating and commenting on both maps made by others and maps that he made himself. You also note that Rudbeck would sometimes redraw maps made by others, like “the Dutch map of the Argonauts’ travels” that he included in his Taflor (Uppsala, 1679). What do we know about Rudbeck’s personal library? Did he annotate all of the maps in his personal library, or only select maps? Did he annotate his books, as well? Did Rudbeck also keep commonplace books? Do similar notes show up in both places?

CF: Unfortunately, Rudbeck’s library is not preserved in its entirety. However, his distinctive handwriting appears in the margins of numerous books at Uppsala University Library. It seems that these were library copies that Rudbeck borrowed and “amended.” He also made an extensive commonplace book that is preserved at the Uppsala University Library, in addition to the folder of his maps and the copy of Taflor kept at the Royal Library in Stockholm.

This has allowed me to study Rudbeck’s note-taking techniques in some detail, and to compare how he used different kinds of media in his work. His central ideas do appear across the material, but the notations on his maps relate in particular to topics such as travel, land usage, and placenames. In my article, I argue that the format of the map tied this information to Sweden’s geography in important ways, that the alphabetically and topically organized commonplace book did not.

CH: Were Rudbeck’s practices of annotating and “revising” maps (by drawing new features or changing the location of features already extant on the map) commonly used by other early modern scholars interested in historical research?

CF: There is evidence that other early modern scholars annotated maps, and maps were definitely used in creative ways to present credible arguments, both in Sweden and elsewhere. In fact, it is clear that Rudbeck expected his audience to be familiar with this kind of scholarly practice, since he used maps (his own and those made by others) to build his argument throughout the Atlantica. Still, there is also a lot we do not yet know about the use of maps (in contrast to the production of maps) in early modern scholarship!

CH: Are other contemporary historians (or geographers, etc.) studying the use of maps by early modern scholars?

CF: There is a growing interest in the use of maps in scholarship, as exemplified in Phillip Koyoumjian’s article “Ownership and Use of Maps in England, 1660–1760.” Questions relating to map use more generally in society also crop up in numerous articles in volume 4 of The History of Cartography (Cartography in the European Enlightenment), edited by Matthew Edney and Mary Pedley.

CH: You write about the intimate connection between ideologies of statehood and empire and Rudbeck’s scholarship and writing, noting that Rudbeck’s “research agenda for the Atlantica” was “closely associated with the interests of the Swedish Empire.” How did Rudbeck first gain favor with Charles XI and other members of elite Swedish society? Did Rudbeck have any qualms regarding the conjunction between his Atlantica project and the Swedish imperial project of expansion and colonization? Was Rudbeck himself a proponent of the Swedish imperial project?

CF: Rudbeck got the attention of the royal family already in his twenties when he exhibited his discoveries of the lymphatic system to Queen Kristina. Later on, he found a powerful patron and promoter in the nobleman, statesman, and chancellor of Uppsala University, Magnus Gabriel De La Gardie, who seems to have been instrumental in securing funding and favor for the Atlantica.

If one thing is certain, it is that Rudbeck did not have a humble personality prone to self-criticism. That is to say, I do not think he had any qualms about aligning his research with imperial ambition. However, he was well aware that his research was controversial. In addition, his style of writing is at times rather humorous. I have been pondering whether Rudbeck believed everything he argued for. This is a difficult question to answer without getting entangled in anachronistic reasoning though. I think historians of scholarship do best in taking what historical subjects said they believed at face value, not trying to second guess or attribute ideas to them that they did not, or even could not, have had. Still, I am not the first to wonder at Rudbeck’s style of expression. It is perhaps best exemplified in the words inscribed on his tombstone: “Imortalem Atlantica, mortalem hic cippus testatur,” which loosely translates to “The Atlantica testifies to his immortality, this stone to his mortality.” That is not the monument of a humble person.

CH: In a recent interview, you reveal that your current research deals with the topic of the sauna in early modern Scandinavia. Can you tell us more about this work? What sparked your interest in the sauna?

CF: Thank you for asking about this, early modern bathing is a topic that fascinates me. I have an ongoing research project on health and morality in the early modern Swedish sauna, or bathhouse, funded by the Swedish Research Council. For this project, I combine perspectives from the history of medicine, the history of the body, and social history to examine the sauna as a place of health and a place of socializing in early modern Swedish society. Evidence from medical advice books, travel accounts, journals, and court protocols show that people visited the sauna when they felt unwell, but also that this created moral tension around undress and secrecy.

CH: I am so ignorant about the history of the sauna, I just have to ask you some basic questions: How was the sauna invented? When did saunas become popular in Sweden?

CF: The practice of taking sweat baths has a very long tradition in northern Europe, with slightly different trajectories in the Nordic countries, Russia, Northern Germany, and Ireland. The oldest archaeological remains are several thousands of years old (or so archeologists tell me). Saunas were popular in Sweden (including Finland) in the medieval period, and they continued to remain popular throughout the eighteenth century. Public sweat baths in France and Germany, in contrast, seems to have closed earlier due to a combination of concerns surrounding both health and morality.

The use of newly digitized court records has been instrumental for my research. The fact that I can search large amounts of texts to find crimes committed in the sauna (and there are plenty) has been absolutely fascinating. For those interested to learn more, keep an eye out for my chapter in the forthcoming volume: Mari Eyice and Charlotta Forss eds., Health and Society in Early Modern Sweden (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, forthcoming 2023).

CH: Are you working on any other projects that you would like to share with our readers?

CF: Apart from my forthcoming volume on health in early modern Sweden, I have handed in another manuscript to the publisher only this last month. It is a monograph, entitled Mapping the Idea of North (Oxford: Bodleian Library Publishing, forthcoming 2024) in which maps take center stage, and where Rudbeck makes a cameo, too. In the book, I explore how the idea of north has been portrayed in different historical and cultural contexts from antiquity to the early twentieth century, highlighting themes such as the importance of indigenous knowledge, exotification, and the difficulty of portraying ice on maps. There is also a chapter on the significance of polar bears, whales, and codfish on maps of the north, and I spend plenty of time on the early modern scholars who believed that the North Pole consisted of a whirlpool surrounded by rivers. Incidentally, this last was an idea that Rudbeck, in a rare role as the voice of reason, firmly rejected as based solely on fictitious conjecture.

CH: The North Pole as a whirlpool!! Can you tell us a little bit more about this? Like, how did this concept come into being?

CF: The idea that there was a whirlpool at the North Pole was central to a fourteenth-century travel narrative entitled Inventio Fortunata that several influential early modern map and globe makers consulted, among the Gerhard Mercator, John Dee, and Martin Behaim. The anonymous traveler behind the narrative claimed to have witnessed a massive whirlpool that drew water into the earth, surrounded by four landmasses with rivers between them. In the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher’s rendition, this led to the conclusion that the water would be expelled again from the earth’s interior at the South Pole. Episodes like these made Mapping the Idea of North a fun book to write, and it gave me plenty of food for thought for reasoning about early modern imaginaries of the environment!

CH: Finally, what are you reading now? Give us three things—books, movies, music, etc.—that excite you right now.

CF: I have just finished reading a lovely novel by the Norwegian author Lars Mytting, called The Bell in the Lake. It is set in north Norway during the last decades of the nineteenth century and details the fate of a medieval Norwegian wooden stave church—an unusual move to say the least—as a means to tell a tale of the coming of modernity, love, friendship, and the relationship of an isolated community to the natural (and perhaps supernatural) world. It made me want to take a trip to rural Norway, though perhaps not during the winter.

It is always risky recommending things you have not finished yet, but I would still like to put in a plug for Babylon Berlin, a TV series set in Weimar Germany. An intriguing story line, good acting, great fashion, and fun interior design, paired with that eerie sense of foreboding that historical hindsight can give, makes this well worth a watch.

One last recent reading that has stayed with me is Nancy Campbell’s The Library of Ice: Readings from a Cold Climate (London: Scribner, 2018). It is a companion piece to Campbell’s collection of poems entitled Disko Bay (London: Enitharmon Press, 2016), and it details her travels through the Arctic in a low key, reflective way. There are plenty of travel books about the northernmost reaches of our globe, but this one manages both to evoke a sense of wonder, and to question the basis for that wonder.

CH: These are fantastic suggestions. I am excited to work my way through all of your recommendations. I think it will be refreshing—and delightful—to read about the Arctic North while living through a hot and humid New York summer.

Thank you, Charlotta, for your time today.

Cynthia Houng is a writer and editor based in New York City, and a doctoral candidate at Princeton University. Her dissertation project, tentatively titled The Art of Judgment and the Judgment of Art, investigates the development of rubrics of aesthetic and economic judgment and valuation in Renaissance and Early Modern Europe. When she is not struggling to decipher mercantesca script, she writes about contemporary art and other aesthetic things. Follow her on Instagram: @cynthiahoung

Featured image: Olof Rudbeck surrounded by ancient authorities, dissecting geography to find a hidden history beneath. Olof Rudbeck, Et Nos Homines in Olof Rudbeck, Taflor (Uppsala, 1679).