By Joseph Cronin

Beverley Southgate (b. 1936) is a history theorist and was one of the pioneers of postmodernism in Britain. His books include: History: What and Why? (1996), Postmodernism in History (2003), What is History For? (2005), and A New Type of History (2015). He is Reader Emeritus in the History of Ideas at the University of Hertfordshire.

Joseph Cronin is Lecturer in Modern German History at Queen Mary University of London. He spoke to Southgate about his life and work in Bloomsbury, London, in September 2022. The transcript was edited by Southgate for style and clarity.

***

JC: You have written quite a number of things about postmodernism, and you are known primarily as the historian who helped to explain the concept to a public audience. So your work is accessible in a field that is not exactly known for its accessibility! With that said, I wonder if you could provide a definition of postmodernism for somebody who isn’t already familiar with it?

BS: It’s certainly a good idea to try and clarify what we’re talking about when we use the term “postmodernism,” and unsurprisingly it’s an extremely slippery concept. Indeed, as I have suggested elsewhere, it might be the archetypal chameleon concept of the later twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. To some it has seemed no more than a passing philosophical fad—an intellectual blip—that had its brief flowering as a fin-de-siècle eccentricity and has already withered and died (itself passed into “history”). For others, though, it represents a theorization of our actual situation—an attempt to describe the cultural situation we find ourselves currently in; and as such, it obviously endures. These two attitudes to postmodernism clearly represent two very different—indeed, contrasting—philosophical outlooks, so it’s hardly surprising that they have periodically come into conflict, with resultant bickering and even outright hostility. These disagreements have become a matter, not only of intellectual debate, but also of highly charged emotional involvement.

This is why it is so important at the outset to try and clarify, so far as is possible, what “postmodernism” actually entails, not least for History. One point of entry might be Jean-François Lyotard, who characterized postmodernism as “an incredulity towards metanarratives.” By that he implied a repudiation of those usually progressive stories that had for so long provided a foundation-stone for histories—in a framework made meaningful by the supposed unfolding revelation of God’s will, or of the progress of rationality, or the development of science and technology. That sort of purposeful movement through time was what was required of History, and it was provided in the form of over-arching narratives assumed to represent what had actually happened in the past and would continue its course into the future.

The denial of such progressive narratives, then, is central to postmodernism’s claims, and Lyotard’s position on that is consistent with Hayden White’s insistence that historical narratives can anyway never be found in the past; they do not simply lie there ready-made and just awaiting resuscitation by historians. On the contrary, it is historians themselves who impose those stories on a past that is otherwise altogether chaotic, lacking shape or direction or meaning. The individual researcher in the archive will recognize that moment when everything—all the muddle of those notes—falls into place and a coherent whole appears at last. I myself experienced such a moment when I suddenly realized that the writings of my research subject—in various fields including theology, natural philosophy, ethics, and politics—could all be seen to express his over-riding attitude towards skepticism; his intellectual life could be interpreted after all as having some coherence. Well, as Hayden White asserts, my revelation and others like it is not of something inherent in the data, already there, but is, rather, a pattern imposed by me and other historians on our otherwise chaotic jumble of disparate material.

In which case, any resulting narrative appears as necessarily “subjective”; it must come from one limited and partial perspective. Historians can no longer claim to be impersonally encountering a meaningful past and reporting on that as if perceiving it “from nowhere.” Instead, they have to take personal responsibility for what is their own construction; their individual choice of narrative will be made on the basis of aesthetics or ethics or simply (for whatever reason) personal preference.

One outcome of the denial of over-arching grand narratives has been a proliferation of mini-narratives, inspired by numerous and varied special-interest groups. These might include women and such racial minorities as have previously, whether deliberately or unthinkingly, been excluded from histories; many are now attempting to reclaim their own places in a past that is now to be more generously shared. In this context, postmodernism can be seen as an umbrella term that embraces a number of smaller movements such as feminism and post-colonialism. All such minority groups form a part of a program of radical decentering that lies at the heart of postmodernism.

JC: Why do you think the debate surrounding postmodernism caused such a furor in the 1990s?

BS: One problem that arises from the “decentering” I’ve just described is that the whole concept of historical truth is brought into question. If the one privileged “absolutist” standpoint of yore is disallowed, and replaced by a multiplicity of viewpoints, we are left with an almost infinite number of contenders for our attention—and how are we to choose between them? Which is the most historically “truthful”? Where they seem to be equally true in their own terms, there are evidently no criteria for choosing between them; so we’re stuck with that problematic word “relativism.” And that has been a major complaint about postmodernism, for relativism obviously poses a serious threat to the absolutist claims of traditional historians—that they aspire, in short, to “the truth” about the past.

So it’s hardly surprising that “postmodernism” became a highly contentious issue when it was at the forefront of theory (philosophy of historiography) in the 1990s. There was then a clear division between “proper” historians, as they were sometimes called, and theoreticians or historians interested in theory. There were definitely two groups, who could sometimes be less than mutually respectful—so yes, disagreements could occasionally degenerate into something of a “furor.” I think a major problem was that postmodernism in its extreme form undermined the very foundations of conventional history. I mean, where would history be without its claim to reach (or at least aspire to) “the truth about the past”? As we’ve just seen, postmodernism removed that claimed relationship with the past as effectively meaningless, so that some, including especially Keith Jenkins, were claiming that “History” had had its day; its time had passed. In which case, the challenge faced by historians could be seen to be not only theoretical but existential.

Postmodernism’s denial of any absolute center from which to view the world or write histories thus re-emphasized a problem that, like so many others, takes us right back to ancient Greece, where relativism is explicitly related to history. The so-called “Father of History” Herodotus travelled widely and noted how different nations required different accounts of the same historical event, and he himself declines to choose definitively between different versions of the past, but presents them all to his readers and leaves them to select their preference. That becomes especially relevant in cases of what we would term “cultural relativism,” in terms of which different peoples can be seen to adopt and embrace different habits and different values. Herodotus recorded the story of the Persian king Darius, who appalled some Greeks by suggesting that they might eat the bodies of their dead fathers, and then horrified some Indians, whose custom it was to eat their ancestors, with talk of the Greek method of disposal, namely, cremation. He notes that, if people were asked which values were best, they would invariably choose their own, “so convinced are they that their own usages far surpass those of all others.” It’s hardy surprising, then, that in the case of national histories there should be wide discrepancies, and Herodotus refers early in his work to a specific example, when an event recorded “according to the Persian story … differs widely from the Phoenician.” No doubt each national narrative could be supported by relevant evidence, but each side might find the questioning of their own version (as assumed to be historically “true”) deeply unsettling. So when cultural relativism became prominent again, it was another reason for historians’ distress.

JC: You remark in one of your books that historians are perceived as “dangerous” by national governments—and not just the authoritarian ones—because historians are able to challenge the narratives about nations’ pasts that governments and civil societies propagate. It struck me that this was an especially pertinent comment. Why do you think that these simplistic and faulty national narratives are so resilient, and even popular?

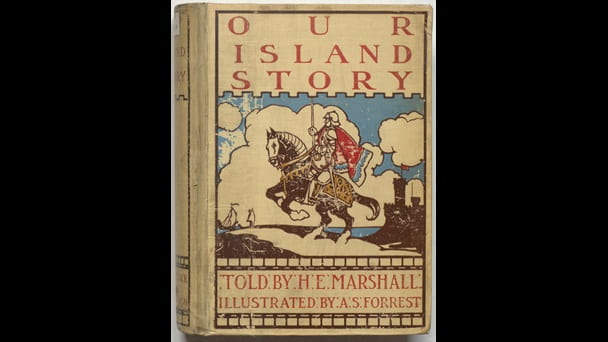

BS: For a start, I hope that by now it has become clear that the idea of a “faulty” national narrative is itself a bit simplistic. How could we ever ascertain whether something as complex as a supposed “national narrative” was “true,” or corresponded with a supposedly “true” series of events? National stories are surely archetypal examples of those “metanarratives” to which Lyotard took exception—narratives that purport to tell a national story (“our island story,” as the British have it), but which are told with very specific political purposes—so are, as we might claim, essentially propaganda. There are numerous cases of nation-states adopting revised histories (or excising past histories) in order to underpin and validate new roles and new directions. To give but one British example, the textbook entitled Our Island Story, first published in 1905, was retrieved and reintroduced by politicians a few years ago in the hope of providing a simple and progressive national narrative that would revivify the country’s ailing patriotism.

Such stirring narratives certainly appeal to some, and are often supported and consolidated by government spokespeople and politically motivated news media. So postmodernists who explicitly reject any such national story, and invalidate its premises, are bound to be unwelcome—perceived as actually “dangerous.” For they are indeed a threat, not only to the required historical narratives, but also to the patriotic commitment supposedly being underpinned. It is perhaps a sad commentary on twenty-first century citizens—of democracies even—that they are often still taken in by demagogic nationalist fervor.

JC: That political observation leads me to another question: one of the main criticisms of postmodernists in the present day is that, through their skepticism about historical “truth,” they paved the way for the so-called “age of post-truth” epitomized by the likes of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, in which facts are contingent, and “alternative” ones can always be found to support the narrative one wishes to propound. How do you respond to this?

BS: Well, in the first place I don’t think that any “philosophy” can be blamed for the intellectual positions of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, not least because I don’t believe that either of them has a clearly articulated intellectual position in their own minds (except perhaps, in both cases, a naive narcissism). But it’s nonetheless surely right that we live in an age of “post-truth” when non-evidence-based narratives are paralleled by blatant politically motivated propaganda. But, as indicated earlier, I think that the spirit of the age produces postmodernism rather than the other way round. And the contingency of “facts” and their appropriation by vested interests has a very long history.

In its extreme form, the skeptical relativism associated with postmodernism can be thought to culminate in denials of the validity of well-attested historical accounts—even to the extent of denying events of which witnesses have personal experience; and the most notorious example of that in our own time has of course been Holocaust denial. It’s very important to sort this matter out, so let’s be clear: no postmodernist that I have ever come across has denied that past events, including those that have come to embrace what has subsequently become known as “the Holocaust,” have actually occurred. I have heard empirical historians complain that postmodernism denies that such traumatic events ever happened—which is obviously an affront to anyone who has personal experience of them, and even to those who are aware of the wealth of evidence that derives from them. But what a postmodernist might well claim is that there is, there can be, no single representation of “the Holocaust.” There can be no one single “truth” about it, no one single all-embracing narrative that could ever comprehend it. There are, after all, innumerable standpoints from which accounts might be given; the very notion of a single “definitive” representation is a nonsense. The concept of one historical “truth” here is simply meaningless. But that does not by any means invalidate the numerous accounts of what went on, whether based on personal testimony or documents or empirical evidence—in other words, the basis of any historical research. And, postmodernism apart, it’s precisely a training in historical procedures that should enable a proper critique of any claims to “facticity” made for whatever reason. (Deborah Lipstadt exemplifies this in the David Irving trial of 2000.)

JC: What drew you to a postmodernist approach to history?

BS: I have more recently tried to answer that question for myself, and have concluded that my own intellectual trajectory seems to conveniently run in parallel with the development of some antecedents of postmodernism. So I hope my attempt to answer your question here may serve to further clarify my views on what constitutes postmodernism. There are, I think, two particular philosophies involved: skepticism and existentialism. Both of these I encountered in my youth, and both certainly influenced my own thought. I’ll take each in turn.

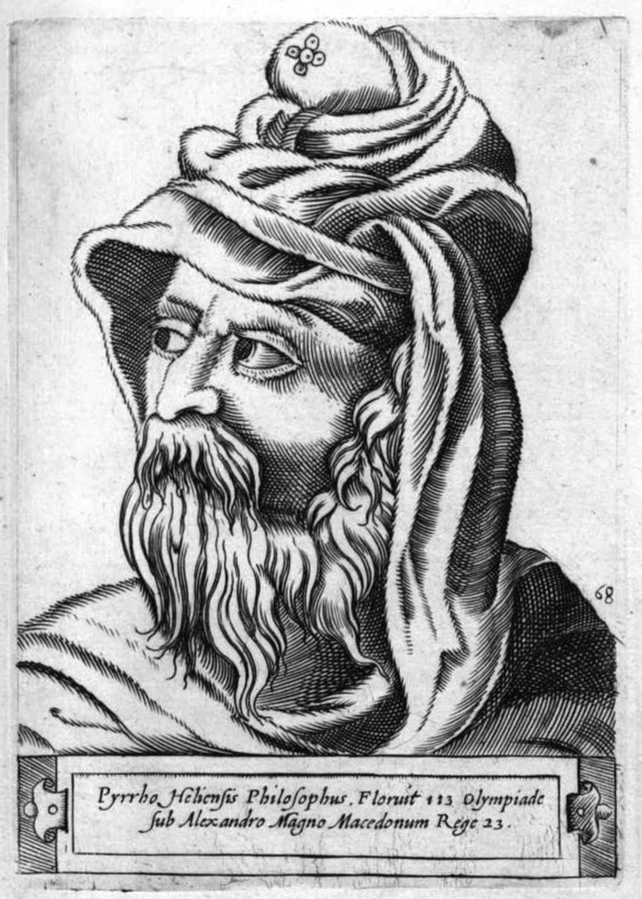

Skepticism, first, dates back to classical antiquity, which formed one foundation of my own education. So for me, the pre-Socratic philosophers already revealed something of interest about the history of thought as it was subsequently to develop: namely, the presentation of theories about the world, which seemed to run in tandem with doubts about whether such theories could ever be valid. In other words, one group of philosophers applied itself to finding out about the external world, while the other turned inwards and examined the validity of whatever was being claimed, problematizing, as we would say, all assumed routes to knowledge, whether empirical or rational. So, whereas scientists (to use the term anachronistically) presented grand theories about the natural world (the nature of matter, the constitution of the heavens), other philosophers questioned whether any such knowledge was ever attainable, in view not least of humans’ very limited capacities. So Thales and his successors in the sixth century BC may tell us that the natural world could be explained by reference to water or whatever, but doubts were articulated by successors in due course. Socrates has long been famed for his acknowledgement that all he knew was that he knew nothing, and some time after Aristotle and others had more or less sorted out the natural world, the doubters appeared. Skeptical philosophers worked out a set of arguments that were synthesized by one Pyrrho of Elis; and then much later Pyrrho’s skeptical philosophy was recorded by Sextus Empiricus, in a written account now translated as Outlines of Pyrrhonism. It was the recovery of that document in the Renaissance that brought the philosophy of skepticism back into the mainstream of European thought, and that revival of skepticism developed in tandem with the development of natural philosophy (or “science” as it became known).

Turning secondly to existentialism, this in my younger days was considered hardly respectable and was the subject of much obloquy—rather like postmodernism later. For in particular it was perceived as potentially disruptive of conventional morality, and so particularly pernicious in the eyes of those who maintained belief in a God who was responsible for individual humans’ creation and subsequent lives. For them, it was heretical to suggest that men and women were responsible for their own lives, which rested on their own choice of what they wanted to be or believed that they should be. Sartre and others had proclaimed that we come into the world without any pre-determined essence, so that it is up to us to decide what to be and what to do (which determines what we are). This sounds like a recipe for a free-for-all, but is not as irresponsible as it might initially sound. That’s because in making our personal choice of what to be, we are choosing not only for ourselves but also for humanity more generally; we are effectively choosing the very nature of humanity, so that in fact the burden is huge.

On a smaller individual scale, we choose how to behave in very different ways, adjusting ourselves in response to different people and events; we are all conscious of doing that, and maybe of adopting different roles. “Each man,” as Shakespeare observes, “in his time plays many parts”; and while the poet might there have been referring to an individual’s chronological development through life from infancy to old age, it is no less the case that we can potentially adopt a variety of roles at any moment. We all recognize that we react to different people and different situations in different ways, provoked to reveal different aspects of our personality in the various circumstances we confront. Sartre observed the way that his restaurant waiter played the role of a waiter, making all the movements and flourishes that were expected of him in his professional capacity. So the fluidity of personal identity is another complicating factor for historians attempting to make some sense of past peoples and events. It’s hard enough for individuals to make sense of their own lives, let alone other people’s. Sartre’s hero Roquentin in his novel Nausea realizes that he can’t just accept his life as “an inconsequential buzzing,” growing “in a haphazard way and in all directions”; he needs, rather, to construct a meaningful narrative, with the moments of his life “follow[ing] one another in an orderly fashion.” Like most of us, he needs to conclude with the sort of narrative described by Virginia Woolf as coming “down beautifully with all their feet on the ground.” Biographies are made to make sense—made to have the appearance of a meaningful trajectory—but that’s possible only in retrospect. So once again, the narrative is not found in the material; it is imposed upon it, and it will retrospectively be made to look aesthetically pleasing or morally edifying, with a sense of purpose. The old suppositions of fixity are once again challenged by existentialism and thence by postmodernism. The stability of personal identity is another victim of postmodernist decentering, and that has serious implications for historical understanding.

So, for me, skepticism plus existentialism, reinforced by an encounter with Keith Jenkins’ classic postmodern text Re-thinking History, published in 1991.

JC: I’ve been thinking about writing a history of postmodernism and history. I suppose that implies that it was a historical moment that has now ended, and I imagine that some postmodernist historians would find that notion irritating, since it implies that their approach is just as subjective, and just as historically contingent, as any other.

BS: Yes, I guess that postmodernism and postmodernists were of their time, and some of us by now might look a bit dated. But while the label may now be scorned and repudiated, much of postmodern theorizing, I would suggest, is now just taken for granted—assimilated into conventional academic practice. Self-reflexivity, for example, is usually taken for a virtue; and there is a greater acceptance of relativism, with serious consideration of different perspectives and alternative views. Respectable historians such as David Cannadine even feel able to make a self-conscious choice of an ethical position, as in his appeal for historiography in the interest of a “shared humanity.” And, after all, a skeptical approach can be seen to leave room for continuing research and alternative hypotheses; so that the use of the description “definitive” seems happily to be in decline. So in sum, not just a passing fashion, but an ongoing attempt to theorize our cultural position.

JC: A final question: could you recommend some of your favorite works of postmodernist history for the uninitiated reader?

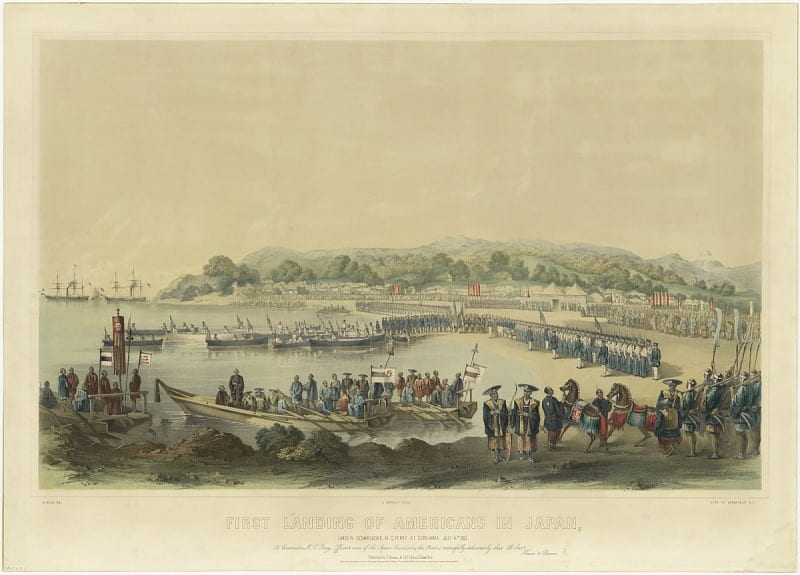

BS: I’m afraid I’ve been out of touch with academia for so long now that I can’t recommend any recent publications. But I can make a suggestion that impressed me in the past. Some time ago I identified some qualities that I’d hope to see exemplified and fostered in a postmodern-style history: in particular, self-reflexivity, linguistic awareness, and tolerance of ambiguity. I found all three of those in a book by the American historian Robert Rosenstone, namely, Mirror in the Shrine: American Encounters with Meiji Japan. Although published what seems now way back in 1988, I missed it for some years since it had seemed irrelevant to my then main interests. So don’t be put off by the title!

Rosenstone has long been interested in historiography, having been the American editor of the journal Rethinking History, and having also written notably on the subject of film and history—where he advocates the medium of film as enabling the presentation of a typically postmodern form of collage, where more or less simultaneous historical events can be presented in other than linear form. His Mirror in the Shrine consists of three historical biographies of Americans who went to Japan in the second half of the nineteenth century. He himself lived in Japan for some time, so is well placed to discuss the American encounter with that country. His book reads almost like a novel, but history it is, complete with such disciplinary paraphernalia as quotations from archival sources. But it’s also history with an explicit moral purpose: to capture the meaning that the lives he is narrating “still has for us.” So he is aiming in short to contribute to the ongoing pursuit of self-understanding.

Self-reflexivity, then, lies at the very core of his book, with history “conscious of itself as an artefact … ambiguous and open-ended.” So, far from trying, in the generally approved manner, to distance himself from his subject, the author here deliberately intrudes in a way that encourages the reader to be aware of the problems encountered and any devices that need to be adopted. Our attention, then, is immediately drawn to the problem of “how and where to begin”; for we have already seen how life stories (as narratives) do not present themselves as coherent and ready-made wholes; the author is responsible for imposing order on to an essentially chaotic jumble of data. It’s only in retrospect that we can make sense of what at the time is experienced as “a shapeless series of disconnected episodes with no movement towards any climax.” So the question of finding a starting-point is already problematic. And biographers can soon face another problem, as they risk turning their chaotic data into something perhaps overly systematic and coherent. They need, rather, to admit where there are gaps and inconsistencies and incompatibilities, for these just reveal the messiness of real lives.

That may alert us in turn to possible problems with so-called primary sources, for authors of news reports, diaries, and journals, for example, may sound like authentic sources, but may themselves have fashioned their material in such a way as to make it easily readable and comprehensible. So that seemingly reliable documents may themselves be anything but. Furthermore, additional care needs to be taken when writers travel to other lands, especially when they travel to somewhere as different from their homeland as was nineteenth-century Japan, where they are confronted by a totally alien culture. On initially making contact with Japan, Rosenstone’s Americans viewed it as inferior—pagan, heathen, and morally degenerate—but as their eyes were gradually opened to the values of Japanese life, they began to compare it favorably with what they had left behind, and so began to invalidate Herodotus’s assumptions about cultural relativism as they came to conclude that “their [i.e. the Japanese] way of doing some things is really the best way.”

In these ways, as he remains open to self-examination, ambiguity, incompleteness, and inconsistency, Robert Rosenstone seems to me to illustrate many of the qualities required of historians, and exemplifies a way of practising history in postmodernity.

Joseph Cronin is Lecturer in Modern German History at Queen Mary University of London. He researches Jewish life in Germany after the Holocaust and Jewish refuge from Nazi persecution in South Asia. He is also interested in the histories of antisemitism, European socialism and, most broadly, the ways in which political decisions, policies and ideologies affect the lives of ordinary people.

Edited by Tom Furse

Featured Image: First Landing of Americans in Japan National Portrait Gallery. Smithsonian.