By Luz Ainaí Morales-Pino

Zarela: novela feminista (Zarela: A Feminist Novel) by Leonor Espinoza de Menéndez (Arequipa, Peru 1876-?), narrates the tragedies of a group of women who, regardless of their best efforts, are vulnerable due to their poor education, the lack of access to a remunerated job and the imperative of marriage as their only resource for survival. Confronting the naturalist discourse dominant in the period, as Gabriela Nouzeilles has noted, the fact that Zarela, the main character, belongs to a line of socially condemned women, none of whom manage to survive, does not determine her destiny. In fact, relating to a positivist ground that considers education as key to progress, once she was abducted by the wealthy—and anti-normative woman– Luisa de Espanet, Zarela manages to change her destiny and that of those around her, thanks to her privileged access to education that led to a paid job. Therefore, the text showcases that blood inheritance, race, or place of origin are not determining forces for the individual, which turns even more relevant when it comes to female subjects traditionally considered as inclined to socio-sexual degeneration. The novel suggests that female subjects are not condemned by their own nature, but by the very dysfunctionalities of a social order that relegates them to the margins. Moreover, in dialogue with what Doris Sommer has conceptualized as the “foundational fictions” of Latin American Literature, the novel presents a happy ending with Zarela’s celebrated marriage to Rafael, a young man who embodies an exemplary masculinity supporting Zarela’s endeavors and considering her an equal.

Understanding marriage as the key to a happy ending marks the ambivalent reading of feminism in the novel, as pointed by Tauzin Castellanos, as well as the silence of the critics. As it usually happens to literature written by women during the 19th and early 20th century, its unclassifiable nature leads to minoritization or erasure. The silence towards the novel strengthens with its murkiness in terms of its date of publication and biographical information about the author (not even a precise date of death). Such absences give an account of women writers’ difficult access to history and historicizations, while they make visible tacit but effective forms of erasure. Never re-edited before, Editorial Aletheya re-launched Zarela in 2020. Among the few critical studies about it, I underscore the works of Isabelle Tauzin Castellanos, Lady Rojas Benavente, and Martha Leticia Salas Pino’s introduction to the newest edition, who refers to the existence of copies only in the Biblioteca Nacional de Arequipa, the Instituto Riva Agüero, and the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú’s digital repository. Tauzin Castellanos agrees with Rojas Benavente in pointing to 1914-1915 as the feasible dates of publication, whereas the PUCP repository indicates the date of 1900 in the file’s metadata. However, this copy of the novel includes a signed dedication by the author, in her own handwriting, with a date of 1910 (based on such annotation, Salas Pino proposes 1910 as the novel’s date of publication). These inconsistencies emphasize the difficulties of anchoring women into the historical discourse, especially when considering this novel written by a woman not based in the capital city of Lima, and with the term “feminist” in its title.

In addition to the problematic metadata, the emphasis on social conflicts during a time when male writers were experimenting with modernism and other aesthetics and ideologies has linked the text to the realist aesthetic. However, realism tends to constitute an overly generic label used to typify proposals that overflow and problematize classifications outlined by the critical tradition. Such classifications respond to what is dominant within certain zones of the cultural field, which leads to a reductionist perspective, especially when it comes to novels written by women. Nevertheless, Zarela is not only a fundamental piece within a genealogy that has still got many missing links, but an eloquent example of how Peruvian women writers of the period used literature as means to problematize the socio-cultural order and the patriarchal aesthetics and ideologies, at the same time as they created what we have conceptualized with Grau-Lleveria as paths for women’s transit towards modernity.

Whereas traditional studies about the literary productions from the turn of the century tend to emphasize the predominance of modernist and decadent aesthetics, as well as the naturalist ideologies, I propose Zarela sheds light upon a silenced aesthetic and ideological line prevalent in women’s writings from the period, which is fundamental to problematizing hegemonic literary histories. Zarela is part of the aesthetics of reform that confront imaginaries that celebrate decadence, degeneration, and the counter normative. Therefore, whereas male writers used literature as a means of escaping their realities (modernist or decadent aesthetics), or as a way of pointing out the total lack of possibilities for our nations (naturalism), women writers such as Leonor Espinoza de Menéndez focused instead on shaping a set of reforms with specific sociosexual agendas.

Despite the title and the novel’s emphasis on women, the reforms proposed in Espinoza de Menéndez’ text illuminate the subtleties of feminist ideology during the turn of the century (as it was conceived by white, lettered women), as well on its subjects, objects, and programs. The women it displays are middle-and-upper class females whose privileged social status impeded them from working and making a living unless married to a wealthy man (usually in troubled and loveless unions condemned to diverse forms of violence). This calls out for an intersectional approach that considers the multiple layers that condition and affect the individual’s existence, opportunities, exclusions, and vulnerabilities, all of which surpass sexual identity. The term “woman” at the time comprised complexities, heterogeneities, and silences. As Lee Skinner explains,

The intersectionality of racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, sexual, and gendered identities means that speaking about “women” entails careful differentiations around race, class, and region […] Many lower-class women in nineteenth century Latin America may have seen their interests as aligned with lower-class men, not with elite women, and many, although not all, white women did not always understand their experiences as similar to those of women of color.

A scene in which Luisa de Espanet, Zarela’s foster mother-to-be, along with her sister and her maid, Rosalía, take advantage of the two poor women who were looking after the baby, Zarela sheds light on the impossible solidarity among women within a perilous system that can only lead to perversion. Luisa de Espanet and her sister run away with Zarela condemning her real mother, Soledad, to a string of misfortunes. Her husband will reject her after their daughter’s disappearance, dying of sadness years later. Moreover, Skinner’s statements turn even more complex if we consider how Rosalía does not express any kind of solidarity towards those women, who were her equals; instead, she is always loyal to her betters. Societal linkages are corrupted and fractured, especially among women, given their vulnerable situation. Therefore, even though the novel presents a reform that aims to improve their situation, racialized and female subjects belonging to lower classes are not Espinoza’s object of concern.

Another relevant tension comes up with the text’s ambivalent feminism, especially if considered from contemporary standards. As stated by Tauzin Castellanos, Zarela’s happy marriage and the need of constantly negotiating with a patriarchal system of consent could seem to neutralize the text’s revolutionary potential. Nevertheless, such ending sheds light on the author’s dialogue with what Eliana Rivero conceptualizes as a feminine feminism: a type of advocacy for women that is willing to adapt itself to the conventions of the patriarchal system, especially when it comes to the roles it outlines for female individuals. Moreover, Zarela’s need to convince the most strong-minded defenders of the patriarchal system, the entomologist Peñaloza and the astronomer Alcázar, discloses the author’s very understanding of feminism as a political praxis that needs conciliation and, foremost, networks of consent to overcome the realm of ethereal ideas. Peñaloza and Alcázar were scientists that used their knowledge to avail their contempt towards Zarela’s feminist agenda in episodes that would qualify nowadays as mansplaining:

Zarelita [little Zarela], my dear daughter—said Mr. Peñaloza in a fatherly tone—how is it possible that you, clever and rational, contribute or, more specifically, create this feminist confusion? How can you oppose the natural laws? Don’t you consider convenient, fair and natural, what is predetermined by such laws and those of the reason, i.e., that woman continues to be the tender hemiptera that accompanies man or the mischievous orthopteron that entertains him and makes life pleasant?

Zarela’s dialogue with male figures that embody a hegemonic knowledge and condescending tone sheds lights on the importance of community and communication for Espinoza Menéndez’ aesthetic and ideological project. Therefore, what would appear conservative from our perspective was, in fact, a strategy of power acquisition fundamental for crafting paths for a feminist agenda whose subtleties do not necessary diminish its potential, as we can see in Zarela’s response:

“Rest assured. The modern woman will continue to be the loving and obedient man’s companion, though more spiritual and suitable for performing the solemn roles of the mother, the educator, and the useful member of society.

Our main aspiration is to be considered equals to men, in the real understanding of equality.”

Zarela’s explanations comply with the need of alleviating men’s anxieties and fears about the emerging paradigm of “the new woman” in European and North American settings, which was considered a threat for male writers and the social establishment of the period. Reinforcing the ethics-aesthetics of reform posed by the novel and its transformative agenda, Zarela’s character manages to turn her main antagonists into advocates of her cause.

The sense of community is also present in the reference to Zarela’s entrance into the university. Rather than embodying an exceptional desire, the narrator comments that Zarela joins the medical school accompanied by a girlfriend whose name and identity, however, we never learn. Entering the university accompanied emphasizes a particular ethical positioning that confronts the traditional masculine modus operandi. Espinoza de Menéndez stresses the need of acting within a network, rather than carrying out the typical egotistic and narcissist endeavors relatable to male figures. Moreover, rather than presenting the network as homogeneous, the novel highlights De Espanet’s participation in it, even when she originally opposed her daughter’s initiative. De Espanet uses her social power and influence to grant the two girls a place in a traditionally masculine setting:

The girls’ presence at the medical school was a novelty. It was so unusual to find skirts there! Some classmates treated them with evident irony. Others were enthusiastic about the possibility of flirting with them. However, the girls’ righteous attitude soon bewildered the ill-intentioned ones. Their non-arrogant severity granted them the respect and consideration they, in fact, deserved. Professors distinguished them with paternal affection, and treated them deferentially, especially when it came to contents that could affect their decency. They knew how to receive the lessons with seclusion and healthy interest. Therefore, they would not be detrimental to their decorum and innocence. They were protected by the ambience of purity that surrounded their noble souls.

Avoiding the possibility of threats, the text continues to link the feminine to a traditional apparel (skirts) and behavior: the girls remain humble and submissive to patriarchal rule, whereas ethically ascending thanks to education. This showcases an eloquent dialogue with other Latin American women writers from the 19th century that used literature as a means for proposing improved projects of modernity that they envisioned as adequate for our context. Such project pose clear confrontations to the traditional 19th century letrados and intellectuals, whose ideas of modernity were grounded in the mere imitationof the European model, leading them later on to disappointment and despair (as we can read in the evasive and dystopic tones of modernist and naturalist fiction of the time). On the contrary, Espinoza de Menendez articulates a feasible project of modernity for the region: one that is even more relevant once we consider the participation of female subjects within the socio-national order with roles that go beyond motherhood and the labor of care—although without discarding them. Additionally, this reformed and Latin Americanist project of modernity dialogues with Martha Nussbaum’s approach to feminism and human development from the notion of capacities, especially what she conceptualizes as the capacity of affiliation. Adding layers of complexity to the narrative about rights, the notion of capacities analyzes the political and social setting in which such rights can actually be exerted. In that sense, the capacity of affiliation to other women becomes key for female subjects’ transit towards modernity. This leads to the articulation of a different imaginary of progress marked by the emphasis on community, rather than individuals, as Zarela complex sociosexual scenarios exemplify.

Luz Ainaí Morales-Pino obtained her Ph.D. in Romance Studies at the University of Miami (2017). She is an Assistant Professor of Spanish American Literature at the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, where she teaches graduate and undergraduate courses on Latin American Literature and Culture. Her research focuses on literary and cultural productions from the 19th and early 20th century Latin America, with emphasis on feminisms, gender studies, visual culture studies, and history of ideas. A selection of previous works is available here.

Edited by Pablo Martínez Gramuglia

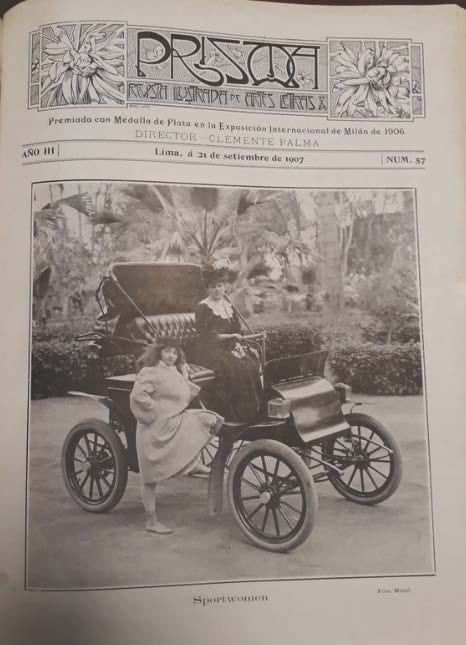

Featured Image: First page of Prisma (Lima, 1907), depicting modern women in a defiant attitude (photo by Marcel Velázquez Castro).