Over its more than 80 years in print, the Journal of the History of Ideas has accumulated a pretty large archive. Oftentimes, that archive is representative of the history of intellectual history—its trends, priorities, methods. Sometimes, it involves scholarship that, by virtue of appearing once-in-a-while, cannot quite get either the visibility or the relevant context in which to be seen.

With the Virtual Issues initiative on the JHIBlog, we propose to recall earlier articles from the JHI that fit with a particular subject or theme, and to place them in a new and current context. We do not pretend that the JHI could ever be comprehensive on these themes, and we are well aware of the limits of the journal’s success in addressing particular subjects. But as with every archive, all sorts of surprises await. With Virtual Issues, we bring out work that has some connection to current concerns, and to recall ways in which authors engaged a particular theme, including ways that may now be out of fashion but that are suggestive of past trends. Each Virtual Issue—the first being Nonhumans in Intellectual History, to appear in several installments—features an introduction that resituates these articles. Anyone interested in curating such an issue together with us should contact the lead JHIBlog editors with a proposal and a list of relevant articles.

— Stefanos Geroulanos, on behalf of the Executive Editors

The second installment of our Virtual Issue feature on Nonhuman Intellectual History provides a selection of articles from the Journal of History of Ideas which have focussed broadly on one central question: how have texts discussed the ‘treatment of animals’? Or to make the anthropocentrism clear, how have humans historically conceptualized animals, their behavioral patterns and their cognitive capacities, and treated them based on that? All the articles in the list below, curated by the executive editor of the JHI, Stefanos Geroulanos, and introduced here by the JHI blog’s primary editor Shuvatri Dasgupta, are inspiring in their own ways. Whilst some focus on Darwin, Aristotle, and similar canonical thinkers to understand ways in which animals were conceptualized, others focus on histories of objects, and also consider encyclopedias as sources for nonhuman knowledge and history. Through these virtual issues on the JHI blog, we hope to provide some methodological indications of what nonhuman intellectual history may look like, and what its stakes would be.

- Passmore, John. “The Treatment of Animals.” Journal of the History of Ideas 36, no. 2 (1975): 195-218. doi:10.2307/2708924.

- Plochmann, George Kimball. “Nature and the Living Thing in Aristotle’s Biology.” Journal of the History of Ideas 14, no. 2 (1953): 167-90. doi:10.2307/2707469.

- Copenhaver, Brian P. “A Tale of Two Fishes: Magical Objects in Natural History from Antiquity Through the Scientific Revolution.” Journal of the History of Ideas 52, no. 3 (1991): 373-98. doi:10.2307/2710043.

- Harrison, Peter. “The Virtues of Animals in Seventeenth-Century Thought.” Journal of the History of Ideas 59, no. 3 (1998): 463-84. doi:10.2307/3653897.

- Rigotti, Francesca. “Biology and Society in the Age of Enlightenment.” Journal of the History of Ideas 47, no. 2 (1986): 215-33. doi:10.2307/2709811.

- Wolloch, Nathaniel. “Christiaan Huygens’s Attitude toward Animals.” Journal of the History of Ideas 61, no. 3 (2000): 415-32. doi:10.2307/3653921.

- Guerrini, Anita. “The Ethics of Animal Experimentation in Seventeenth-Century England.” Journal of the History of Ideas 50, no. 3 (1989): 391-407. doi:10.2307/2709568.

- Margócsy, Dániel. “Refer to Folio and Number”: Encyclopedias, the Exchange of Curiosities, and Practices of Identification before Linnaeus.” Journal of the History of Ideas 71, no. 1 (2010): 63-89. doi:10.1353/jhi.0.0069.

- Preece, Rod. “Darwinism, Christianity, and the Great Vivisection Debate.” Journal of the History of Ideas 64, no. 3 (2003): 399-419. doi:10.2307/3654233.

- Evans, Mary Alice. “Mimicry and the Darwinian Heritage.” Journal of the History of Ideas 26, no. 2 (1965): 211-20. doi:10.2307/2708228.

- Grene, Marjorie. “Aristotle and Modern Biology.” Journal of the History of Ideas 33, no. 3 (1972): 395-424. doi:10.2307/2709043.

- McCalla, Arthur. “Palingenesie Philosophique to Palingenesie Sociale: From a Scientific Ideology to a Historical Ideology.” Journal of the History of Ideas 55, no. 3 (1994): 421-39. doi:10.2307/2709848.

As I mentioned before, it is better to acknowledge at the outset, the anthropocentrism that the question of ‘treatment of animals’ itself is laden with. It is related to the scarcity of intellectual histories which can potentially engage with the ways in which animals have treated each other. In order to address this, it is imperative to move beyond the text as the sole source for intellectual history writing, and open the doors for interdisciplinary methods inspired by biology, anthropology, and feminist theory. This is not to reject the textuality altogether, but rather to suggest that reading texts such as Aristotle on the behavior of bees, alongside works of biologists like Thomas D. Seeley provides a crucial indication of the ways in which we can address this question. In this regard, pioneering work of Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlika titled ‘Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights’ provides some methodological indications on how the discipline of political thought might consider animals as actors within their own sovereign and self-sustaining communities. Through that the authors place animals at the heart of political theory and construct the nonhuman subject as a rights bearing political actor. Anthropologists and biologists have observed animal behavior towards one another which have enriched us with crucial insights on animal labor theory, socio-political organization, nonhuman kinship and care, and mutual interdependence.

The other methodological stake which calls for discussion within the context of these groundbreaking articles from the JHI archive is the question of Eurocentrism, and how that shapes the field of nonhuman intellectual history. Buddhist and Jain political theologies in South and Southeast Asia were sustained on a foundation of animal ethics and morality. In recent times scholars have devised creative methodologies for thinking about the nonhuman in non Eurocentric ways. Sugata Roy’s innovative work ‘Climate Change and the Art of Devotion’ shows how manuscripts and their illustrations can be thought of as sources for an art history of climate change, animal treatment and habitat. Sumana Roy’s fantastic work ‘How I Became a Tree’ engages with approaches towards trees and animals in literary texts and thinkers from within and beyond South Asia.

There is much to be done in terms of thinking about animals as meaning-makers. It would require posing questions which elude easy answers such as: where and how can we locate animal agency within anthropocentric archives, which have their own set of violent hierarchies (of class, race, gender, caste, and ethnicity)? It would require methodological innovations such as considering observational studies, and oral histories, alongside canonical and non-canonical textual sources. At times, it would need moving beyond textual sources, and taking into account visual archives. Moreover, it would need intellectual historians to rethink the species divide. The methodology for thinking about nonhuman intellectual history focusing on animals would need to be based on an ethics of care-giving as a means to move beyond anthropocentrism. Within that framework, caring for the nonhuman would place them as agents of their own narrative. Caring would also enable historians to move beyond their authorial subjectivities as chroniclers of these animal intellectual histories, and account for the implicit epistemic hierarchies embedded within archives. Thus, it would allow their subjects to articulate their stories, and this caring methodology would therefore manifest as letting the nonhuman speak in ways that it has always desired!

Shuvatri Dasgupta received a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree in History from Presidency University, Kolkata, India. She was also an exchange student and Charpak Fellow at Sciences Po Paris (Reims campus), studying for a certificate programme in European Affairs and B1 French. She is the editor of the Journal of History of Ideas blog, and a doctoral candidate in the Faculty of History, University of Cambridge, funded by the Cambridge Trust and Rajiv Gandhi Foundation Fellowship. Her doctoral dissertation is tentatively titled “A History of Conjugality: On Patriarchy, Caste, and Capital, in the British Empire c.1872-1947”. Her general research interests include global history, gender history, intellectual history and political thought, histories of empire, histories of capitalism, Marxist and Marxist-Feminist theory, and critical theory. For the academic year of 2021-22 she is the convenor of the research network ‘Grammars of Marriage and Desire’ (GoMAD) supported by CRASSH, Cambridge, and the Histories of Race Graduate Workshop, at the Faculty of History, University of Cambridge.

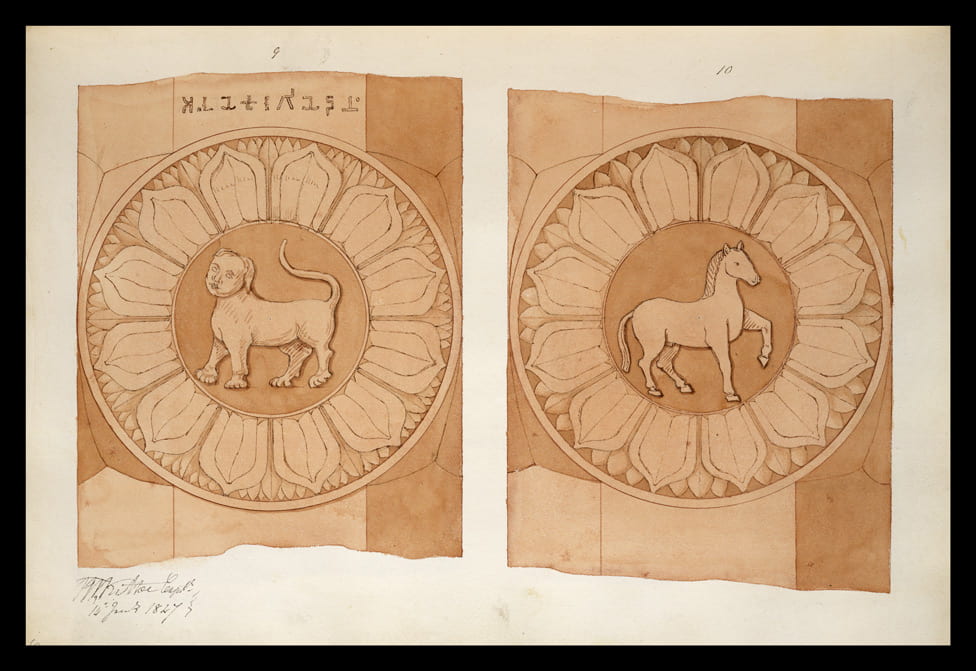

Featured Image: Wash drawing of a sculptured post from the railing of the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodhgaya, by Markham Kittoe, 19th Century. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.