By Zachary Clary

Reminiscing on his time as a schoolteacher at a predominantly Mexican-American school in Cotulla, Texas, President Lyndon Johnson admitted that he “never thought in [his] fondest dreams that [he] might have the chance to help the sons and daughters of [his] students and to help people like them all over this country.” After becoming president, Johnson acknowledged “that now [he did] have that chance, and…[he meant] to use it.” Best summarized by historian Robert Dallek, Johnson’s belief in an activist government firmly established his reputation as a “liberal nationalist, an advocate of Federal programs that had a redefining influence on American life.” An ambitious New Dealer and a stalwart supporter of President Franklin Roosevelt, Johnson conceived of the federal government as a positive force that could reinvigorate the South’s reputation on the national stage, raise the quality of life for impoverished Americans, and protect the rights of historically marginalized American citizens, including African Americans, Native Americans, Latin Americans, and poor whites.

Regardless of his commitment to improving the lives of everyday people, however, Johnson’s administration and legacy are inextricably linked to and rightfully tainted by his decision to escalate American involvement in the Vietnam War. Johnson’s ill-advised choice needlessly prolonged the conflict, destroyed his approval rating, undermined his domestic programs, and, according to some estimates, resulted in upwards of 55,000 American deaths and at least 882,000 Vietnamese deaths. Haunted by the specter of Vietnam, Johnson’s historical reputation continues to suffer. As revealed in a 2017 Gallup Poll, 65% percent of Americans consider Johnson’s presidential performance average or below average. Furthermore, a 2016 poll that asked Americans to select the best Democratic president from a list ranked Lyndon Johnson as last, with only 2% of the vote.

According to biographer Doris Kearns Goodwin, who ghostwrote Johnson’s 1971 memoir, Johnson even recognized the uncomfortable concessions he made to continue the fight in Vietnam: “I knew from the start that…if I left the woman I really loved—the Great Society—in order to get involved with that bitch of a war on the other side of the world, then I would lose everything at home. All my programs. All my hopes to feed the hungry and shelter the homeless.” Why, then, did Johnson trade his social reforms for what proved to be a deeply unpopular and seemingly unwinnable war? How did Johnson’s unwavering commitment to anticommunism and global interventionism comport with his espoused views as a liberal nationalist and social reformer? Put simply, how and why did Johnson consider American military involvement in an ideological war in Southeast Asia a worthwhile cause that would benefit American interests and, more importantly, the lives of the American people?

This article is not concerned with whether America’s increased involvement in Vietnam was inevitable, a bitterly contested and well-developed component of the historical literature. Instead, I start with the assumption that Johnson, a devoted and somewhat militant anticommunist, actively decided to wage the Vietnam War. From there, I analyze how Johnson understood and justified this choice as part of his larger political ideology. At the same time, I accept at face value Dallek’s contention that Johnson, despite his proclivity for political chicanery, was a genuine liberal nationalist interested in solving domestic problems with government solutions. Undoubtedly devoted to the ethos of domestic liberalism established in the 1930s, Johnson weighed his choices and sacrificed many of his beloved social programs to pay for the increasingly costly Vietnam War in American lives and American tax dollars.

Liberal nationalism, according to political scientist and legal scholar Michael Lind, “might be most simply defined as yesterday’s ‘melting pot’ nationalism updated to favor the cultural fusion and genetic amalgamation not just of white immigrant groups but of Americans of all races.” Taking office at the zenith of Democratic power in the twentieth century, Johnson eagerly embraced the longstanding notions of American exceptionalism and primacy on the international stage, both of which gained steam in the aftermath of World War II. At the same time, Johnson’s view of nationalism was expansive enough to include the diverse coalition of racial, ethnic, cultural, and geographic identities found within the United States, thus firmly positioning him in the liberal nationalist camp. Circumventing the nativist connotations typically associated with nationalist ideology, liberal nationalists consider national unity less a product of homogenous social constructs and more the result of a shared political culture. As explained by Vice President Hubert Humphrey, a noted liberal nationalist and trained political scientist, nationhood engenders “the struggle to create national unity out of religious and linguistic and even geographic fragments…and the struggle to create both wealth and justice, to create a society of expanding opportunities and hope.” Proponents of internationalism and multiculturalism, liberal nationalists believed (1) that the diverse identities of American citizens all contributed to a singular, shared national identity and (2) that it was the federal government’s implicit obligation to preserve this national identity and improve the lives of the American people.

When interpreted through the lens of liberal nationalism as outlined above, then, Johnson’s ambitious domestic programs, known collectively as the Great Society, and the groundbreaking civil liberties protections implemented during his administration are clearly reflective of his ideological and personal commitment to both the United States and the American people. Conversely, the Vietnam War, which Johnson waged with substantively more vigor than his War on Poverty, is a bit more difficult to understand in terms of Johnson’s liberal nationalism. In fact, the war’s expenditures forced Johnson to turn his back on the needs of the American people, many of whom remained impoverished, in order to defend South Vietnam from a perceived threat to its ideological and national security: Communist North Vietnam and their Chinese and Soviet allies. Discounting the larger political considerations that some historians argue forced Johnson’s hand, including a powerful pro-war camp in the US Congress and a robust anticommunist mentality in the United States, this decision was Johnson’s alone. Historian George Herring further demonstrates that Johnson, despite having numerous opportunities to reduce American involvement in the region, routinely refused to back down.

Nevertheless, Johnson’s Vietnam policy was not, as some historians have reductively suggested, an intensely insecure man’s desperate attempt to avoid being the first American president to face a substantive military defeat. American involvement in Vietnam was, in Johnson’s view, necessary to protect the democratic processes that made possible the liberal reforms carried out by his activist US government. As Johnson told a crowd at Johns Hopkins University in a 1965 speech outlining the necessity of American involvement in Vietnam, “we fight because we must if we are to live in a world where every country can shape its own destiny. And only in such a world will our freedom be finally secure.” Cognizant of America’s global reputation as a bastion of democracy, Johnson asserted that the precepts of American liberal thought, including individualism and self-determination, could only be preserved if they were allowed to function across the globe. Returning to this theme in 1967, Johnson contended that totalitarian (meaning Communist) aggression in a region as distant as Southeast Asia was still “a threat…to the United States of America and to the peace and security of the entire world of which we in America are a very vital part.” As Johnson saw it, the fall of South Vietnam could set off a chain reaction that would diminish America’s legitimacy on the international stage, embolden a wave of authoritarian and anti-democratic regimes across the globe, and disrupt the very foundations of the existing world order. Although Johnson understood that his decision to Americanize the Vietnam War would inevitably disrupt the efficacy and longevity of his Great Society programs, his liberal nationalist impulses compelled him to confront the crisis in Vietnam, which he considered a threat to both democracy and the American national identity, before returning to the social programs and economic reforms he hoped to implement in the United States.

That is not to say, of course, that Johnson was correct in his understanding of what failure in Vietnam might mean for America’s international reputation or the future of democracy. In fact, the evidence strongly suggests that Johnson’s interpretation of America’s precarious position on the international stage during the 1960s was rather flawed. For example, even though the United States inevitably failed to halt the Northern takeover of Vietnam, the Soviet Union collapsed under its own weight in the 1990s. At the same time, Johnson’s proposed domestic and economic reforms, most of which he put on hold to fight the war in Vietnam with the hope that future administrations would pick up where he left off, have yet to be taken seriously by the federal government. In fact, fifty years after Johnson declared War on Poverty, the number of Americans living below the poverty line has only decreased by 4%, and the vast majority of the nation’s impoverished population still resides in dilapidated cities and underdeveloped rural communities.

President Lyndon Johnson was forced to choose between two uniquely challenging programs: (1) a previously unimaginable domestic agenda that would greatly improve the quality of life for countless Americans or (2) an uncertain international crisis that, according to many of his trusted advisors, had the potential to destroy the apparatus of containment that was keeping Communist encroachment at bay. Reflecting on his options and the potential consequences of each course of action, Johnson decided that victory in Vietnam was the best if not the only way to protect American interests from the perceived threat of international Communism. Displeased with the choices that were presented to him, Johnson prioritized taking actions that would protect American interests in the long-term, even if it meant neglecting policies that would have immediately benefited the American people.

Rightfully critiqued for his decision to Americanize the Vietnam War, Lyndon Johnson was, nonetheless, operating within his overarching political ideology when weighing his options, none of which seemed hopeful. A liberal nationalist, Lyndon Johnson believed that it was his duty to protect the American national identity, which was inextricably linked to the political culture shared by all Americans. As such, the survival of democratic nations abroad was, in Johnson’s mind, vital for continued progress in the United States and, thus, took precedent over the Great Society. Lyndon Johnson never stopped using his position of power to help people in need; however, he believed that future reforms, whether in healthcare, education, race relations, or economic policy, would only be possible if the United States retained both its position of power on the international stage and the prosperity that accompanied it.

Shortly following his retirement from public office, Lyndon Johnson acknowledged that “everything that went wrong in Vietnam that’s being criticized…was [his] decision.” This quip, which Johnson made in passing, may have been one of the only times during Johnson’s career that he was correct when speaking about Vietnam. That said, Johnson’s failures and foibles in foreign policy, which were numerous, were not entirely self-serving or anti-ideological. This is not to say that Johnson’s actions are defensible, or that American involvement in the Vietnam War was justified. My argument is simply that Johnson’s choices regarding Vietnam, including the negative impact they had on his Great Society, complied with his liberal nationalist beliefs. Lyndon Johnson’s choice to Americanize the Vietnam War is rightfully considered one of the worst foreign policy disasters in American history. Despite the seemingly antinationalist implications of an interventionist war that directly hindered domestic progress, however, Johnson did consider the domestic ramifications of his actions before escalating the Vietnam War. Lyndon Johnson may have been wrong about Vietnam, but the thought processes behind his flawed decisions were consistent with his ideological identity.

Zachary Clary is a History PhD student at the University of South Carolina. His research explores the racialized memory of the American Revolution, as expressed in the political discourse of the twentieth century. His interests include twentieth century political ideology and expression, the politics of race in the United States, and historical memory.

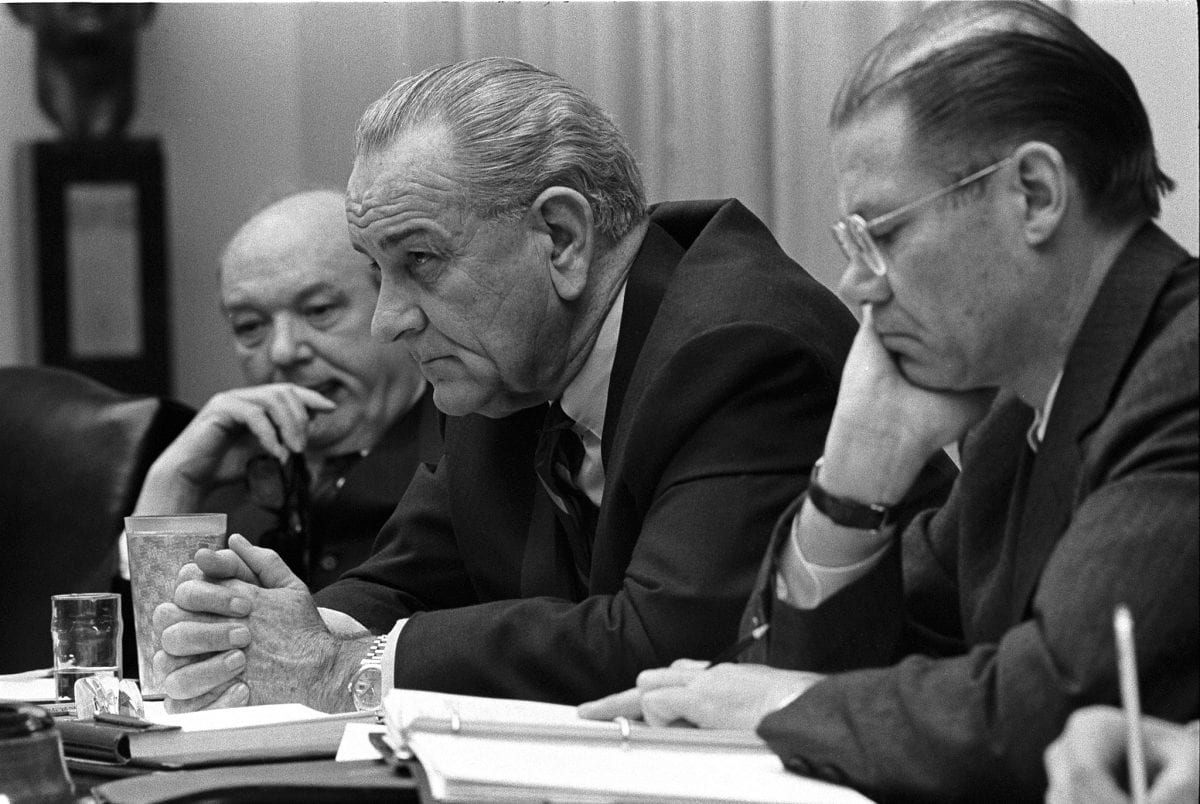

Featured Image: Secretary of State Dean Rusk, President Lyndon B. Johnson, and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara at a meeting in the Cabinet Room of the White House. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.