By Stephanie Redekop

The mid-twentieth century United States was, American poet Randall Jarrell wrote in 1953, an “age of criticism”: a period in which criticism became the “representative or Archetypal act” of the humanistic intellectual (p. 66). For many of these intellectuals and critics, the essay was the preferred medium of expression. Phillip Lopate recently identified the period from 1945-1970 as “the Golden Age of the American Essay.” In the decades since, essays have also become “the lingua franca of the American academy,” which developed an increasingly tight affiliation with public intellectual work in the United States after World War II. In other words, intellectual historians of the post-1945 period in the United States often have no choice but to contend with essays in our research. But what does it mean to read essays as evidence?

Because essays are a genre of literary nonfiction, we risk missing important aspects of their cultural work if we only read them for their informational or ideological content without attending to matters of genre, form, and style. For this reason, scholars of the essay offer several insights pertinent to reading essays for the purposes of intellectual history or intellectual biography.

What is an essay? A notoriously fraught and “open” form, Graham Good provides us with a useful working definition: essays are typically short nonfictional prose texts that are “provisional and exploratory, rather than systematic and definitive”; they derive authority from the essayist’s “personality” rather than their formal credentials or technical vocabulary; and their concerns are typically “personal and particular.” Though the essay may appear similar to other nonfictional prose genres, like the article, Robert Atwan argues that the designation of essay is most appropriate “when the writer’s reflections on a topic become as compelling as the topic itself,” when the piece’s style and methods demonstrate its subject’s complexity or resonance with broader themes. As a result, the essay is itself a complex form that requires literary interpretation; it is not “a straightforward and transparent form of exposition,” but rather an “an enactment of thought and a projection of personality that use[s] language dramatically” (p. xxxvi).

It is these two qualities that may be of particular interest when reading essays for the purposes of intellectual history: essays derive authority from the personality of the essayist, and they present their ideas through a dramatization of thought.

First, understanding the essay as a literary genre means acknowledging that, even though essays are “grounded in the illusion of their artlessness” and offer an impression of candor or transparency, this impression is itself a literary effect. In fact, most essay theorists emphasize that essays derive their authority from the projected personality of the author. Nicole Wallack identifies the “single most important quality of the essay as a literary form” to be the essayist’s “presence” (p. 15). Writers can create this “presence” by including personal experience as evidence, creating a distinctive voice, and establishing a clear point of view (p. 2-6). In other words, an essayist’s presence does not necessarily arise from the use of the first-person; it is also shaped by the their distinctive style, posture, and perspective.

Reading essays with an attention to the writer’s presence can have important interpretive implications. For instance, we might ask: what is the basis of this essayist’s authority? What kinds of knowledge do they represent themselves to have, and what does it mean for them to know? Reading “A Stranger in the Village” by James Baldwin, for example, Wallack asks us to carefully consider Baldwin’s decision to supply personal experience as evidence and to write from a first-person point of view, rather than take these decisions for granted (p. 66). What is at stake in Baldwin’s decision to present potentially abstract concepts in these personal terms? Though Wallack poses this question as a scholar of writing and rhetoric, it bears historical implications as well. Baldwin’s essays frequently establish a collective first-person point of view (“we”), using what Cheryl Wall has called “strategic American exceptionalism” to interrogate the construction of American identity (p. 120). Likewise, in using the form of the personal essay to bring his identity and experience as a Black American to the fore, Baldwin emphasizes the personal impacts of social systems and demonstrates the twentieth-century alignment between freedom and personal identity (p. 16, 21).

Stephen Schryer examines the ways in which mid-twentieth-century essayists writing for William F. Buckley’s National Review construct a rhetorical posture of “anti-intellectual intellectual[ism].” In so doing, Schryer encourages us to consider what strategies a given essayist uses to identify and position themself as a knowledge authority. His attention to stylistic patterns in the self-positioning of National Review essayists such as Hugh Kenner and Joan Didion — including, notably, their maverick sensibility — allows Schryer to untangle the “contradictory strains of elitism and populism” competing within 1960s conservatism. As these scholars demonstrate, the intellectual work of an essay extends beyond the ideas that it describes, and those ideas themselves are shaped by the self-representation of the essayist.

Second, an essay is a dramatization of thought. Essays tend to communicate their core ideas dramatically, drawing attention to those ideas’ development or genealogy and presenting them as arising out of concrete particulars. An essay does not only transmit ideas as information; rather, it conveys the story of how those ideas have been formed or experienced by the writer (p. x). Unlike articles, essays do not necessarily present those ideas systematically or lead with a straightforward thesis. Therefore, instead of working to extract a thesis, we should contend with the essayist’s decision to present ideas otherwise. Theodor Adorno, for example, argues that essayists’ refusal to privilege abstract concepts above individual particulars actively resists “equating knowledge with organized science”. In the same way, he writes, an essay “shakes off the illusion of a simple and fundamentally logical world, an illusion well suited to the defense of the status quo”.

Essays function as works of intellectual storytelling, which in turn affects the ways in which they represent what information is and what information does. In the book Tough Enough, which examines the “unsentimental” styles and related ethical frameworks presented by a range of women essayists in the mid-twentieth century, Deborah Nelson suggests that “facing the facts” in these essays requires that we not only identify “what is happening,” but also confront what it means “to be changed by that knowledge” (p. 14). As Nelson demonstrates, reading essays requires engaging with both facts and aesthetic experience.

With these essential literary dimensions of essays’ work in mind, intellectual historians also have much to offer the field of essay studies. The field’s emphasis on advancing stylistic or rhetorical analyses of individual essays has sometimes come at the expense of examining those essays’ historicity. Making a case for essays’ literary value has often been expressed in the language of their timelessness: in Cynthia Ozick’s often-cited formulation, essays differ from articles because they transcend the moment of their composition. Today, essays often find their way to readers in the form of sweeping anthologies. But from this vantage, it can be more difficult to identify an essay’s timeliness, the way that it has arisen out of specific moments, contributed to specific discourses, and been addressed to specific audiences. Therefore, as scholars like Wallack and John J. Pauly have argued, essay studies will strongly benefit from deeper institutional and intellectual histories that situate essays within the broader discourses that they have engaged and helped to shape.

The essay genre is explicitly invested in exploring the interrelation between concrete particulars and the broader ideas with which they resonate. As such, essays are often sources well suited to the aims of intellectual history. The scholars of post-1945 American essays whom I have cited above demonstrate how essays’ literary dimensions also reveal important aspects of their ideological content. Nelson models the strengths of this approach particularly well in Tough Enough. Although she acknowledges that the artists and intellectuals whom she studies do not constitute a recognizable intellectual group, she makes a persuasive case for grouping them based upon the commonalities in their essays’ “style and outlook”— namely, their unsentimentality. Likewise, by understanding this un-sentimentality to be an aesthetic and ethical “choice rather than character trait,” Nelson moves beyond isolated readings of individual essayists to instead complicate historical narratives about “our relationship to suffering” after 1945 (p. 1-3). As I have argued, essayists’ formal and stylistic decisions are deeply shaped by underlying ideas about knowledge, authority, and the public sphere. Therefore, intellectual historians should consider what ideas animate and take shape from an essay’s formal and stylistic elements, in addition to the historical and intellectual discourses with which the essayist is directly engaged.

Stephanie Redekop is a PhD Candidate in the Department of English at the University of Toronto and a Junior Fellow at Massey College. Her research charts a literary history of the role of facts in American public discourse of the 1960s and is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

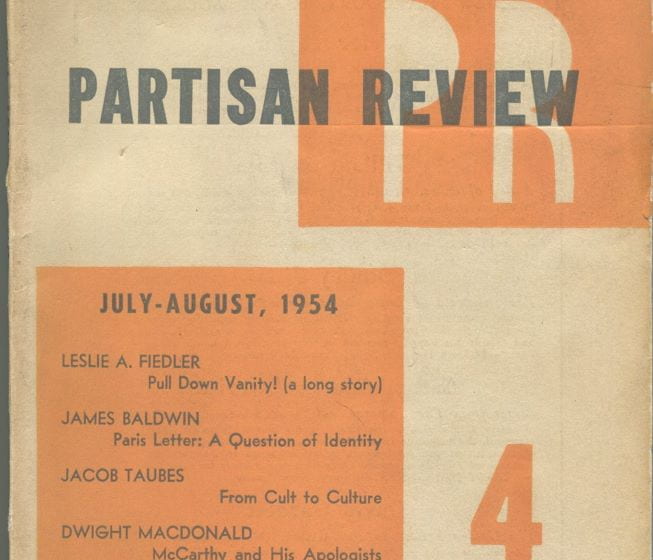

Featured Image: Cover of Partisan Review Vol. 21 No.4 (July-August 1954)