Pranav Jain

Jack Tannous, The Making of the Medieval Middle East: Religion, Society, and Simple Believers (Princeton, 2018)

This extraordinarily erudite book asks big questions and offers even bigger answers. Its aim is nothing less than to explain the “nature and significance of non elite Christianity and the mechanics and pace of Christianization/Islamization.” (xiv) Regarding the former, Tannous’s main contention is that the late antique/early medieval Middle East was home to many “simple believers.” As he explains:

“The great majority of Christians in the Middle East, I will suggest in Part I of this book, belonged to what church leaders referred to as ‘the simple.’ They were overwhelmingly agrarian, mostly illiterate, and likely had little understanding of the theological complexities that split apart the Christian community in the region. ‘Simple’ here does not connote ‘simple-minded,’ as it might in some varieties of English, nor should it be understood as a category restricted to the laity: there were monks, priests, and even bishops who were simple believers. The men who wrote the texts we study lived their lives among these simple believers: they fed them and ate with them, they prayed with them and for them, they taught and healed them, and they had the responsibility of pastoral care for them. A key to understanding the world that the Arabs found is the recognition that it was overwhelmingly one of simple, ordinary Christians; and that it was a world fracturing into rival groups on the basis of disagreements that most of those Christians could not fully understand.” (3)

With relation to the origins of Islam, he suggests that putting ‘simple belivers’ at the centre of analysis leads us to ask very different questions: “…what does putting the simple at the center of our story do for our understanding of the world the Arab conquests created? For the moment, we can make a slight (and as we will see, provisional) change to the question we have been asking. The question now becomes: What happened when a politically dominant religious rival to Christianity appeared in the Middle East, one whose strongest theological criticisms of Christianity centered on doctrines—the Trinity and the Incarnation—that simple believers could not understand fully or properly?” (221)

As a non-specialist, I am not qualified to judge the merits of Tannous’s arguments within their historiographical context. However, the range of the book’s evidence and arguments makes it worth reading for any historian of religion, regardless of what period/religion they work on. I personally found it very interesting to see how historiographically different debates about late antique Christianity/early Islam are from my own field of study (early modern Europe), even though, in a broad sense, both fields are trying to ask similar questions about the nature of religious belief and the relationship between complex doctrines and everyday practices. My only qualm is the single mindedness with which Tannous pursues his arguments. Though he certainly gets his points across, I was left with some doubts about how fair his characterization of the work of his fellow scholars was. Regardless, a very rewarding read!

Nuala Caomhanach

Machines are like techno-shadows to humans. Like a visiting guest that overstays their welcome, we enjoy them for a wee bit, get bored of them, wish they would get lost, then freak out when we do lose them, then become nostalgic when they are gone. Machines seem to cohabit, to parasitize but are symbionts to our lives, we created them but fear they may destroy us. Machines are our companions here to stay. Uber uses machine learning for estimated time of arrivals for rides, UberEats for delivery time, planes have autopilot (as far back as 1914!) of which up to seven minutes are human powered. All aspects of our lives are infiltrated by machines and artificial intelligence. After attending In our Image: Artificial Intelligence and the Humanities hosted by the National Humanities Centre I started to read more about the social and political implications of machines and artificial intelligence in our lives. **Of course the algorithms behind the online books I choose to read highlighted other similar books–thanks machine learning technology. Let’s not ask did I have free will here at all. That’s for the next reading recommendations!**

Meredith Broussard’s Artificial Unintelligence: How Computers Misunderstand the World (2018) along with her New York Times piece “When Algorithms Give Real Students Imaginary Grades” is a good place to start as Broussard has a knack of grounding the sociological analysis in an accessible technical account of the major computational processes involved in machine learning. This book is non-technical reader friendly. The book maps out the socially-constructed nature of technologies that are inevitably embedded with the cultural and political values of their designers, developers and programmers. Ever think about how most “robots” are female, Amelia, Siri, Alexa etc. especially those who are designed to serve us humans? Broussard’s engrossing book demonstrates how machine learning–which is a model of making predictions based off pattern recognition within reams of data –simply perpetuate structural social inequalities, such as racial discrimination. By sharing her own experience as a data journalist and programmer she explains how these biases need to be consciously designed out of the system. At the heart of her argument is the issue of the failure of self-governance within the tech community that has led to an urgent need for ethical and legal education of developers. Her work adds to the critique of not only the tech “bro” culture but also how this techno-chauvinism permeates the coding of artificial intelligence.

Two books explore the myth of technological neutrality—the notion that technology and tech creators are neutral actors free of impolict ethical and moral dimensions and values: Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (2019) and Safiya Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (2018). As noted in my introduction, as technology becomes increasingly ubiquitous we hear of more and more troubling tech incidents, such as facial recognition softare claiming to know if you are gay, or Google photo labelling Black people as gorillas. Many scholars are questioning the exalted status of technology in society. Benjamin explores the ways in which modern technology creates, supports, and amplifies racism and white supremacy. She provides stacks of evidence for her argument–from robot labour and predictive policing systems to AI-judged beauty contests–hence broadening the tech term “coding” away from its narrow meaning within computer science to the way in which races, ethnicity, and names are themselves code and are coded with important information. Her central argument is that we are living in the ‘New Jim Code’ era where technologies replicate existing inequities and hide behind the modern vision that machines are more objective than humans. Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression (2018) focuses on the use of the internet and search engines, especially Google search, by applying an intersectional analysis of racial, ethinic and gender. In this fascinating book, Noble unmasks the Wizard of Oz– the human(s) behind algorithmic-driven software, artificial intelligence technologies, and computer-generated automation. She demonstrates how search engines structure knowledge, reflect racialized cultural, social, and economic values, and ultimately legitimize dominant group ideologies that oppress marginalized racial identities. All our interactions with information are heavily curated and mediated and propagate cultural stereotypes, particularly Black culture. She highlights the real issue in society is that we take for granted that information is reliable and credible because it’s just there for everyone to access.

Taken together these books highlight, as a matter of human rights, that individuals and groups lack control over how personal information is indexed, studied, stored and who has access to it. They all suggest that the importance of human-centric design and human-machine collaboration is required to counterbalance the inherent biases within coding and the male-dominated tech world. Each author offers a provocation or solution to this issue of corporate control over public access to information. For Broussard, there may be better and more obvious low-tech solutions–for example, greater investment in public edition, or transportation. Noble and Benjamin envision an ethical algorithmic future and offer practical solutions, for example, challenging the privatization of the internet , they advocate for government regulation to break up large tech monopolies that threaten democracy in the information sector and call on public policy to foster noncommercial search engines and information portals.

If this is an area of interest, look out for Wendy Chun, “Red Pill Toxicity, or Liberation Envy” Discriminating Data (The MIT Press, forthcoming) and have a read of Mar Hicks, Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing (next on my list).

Shuvatri Dasgupta

Françoise Vergès, A Decolonial Feminism (Pluto Press, April 2021)

In this powerful text, the author brings out the intersections of anti-patriarchal and anti-imperialist politics through the category of ‘disposability’. Vergès illustrates how capitalism functions by oppressing women of colour more than white women. Although the labor of women of colour is crucial, capitalists keep these forms of labor invisibilized, maintaining its alliance with hierarchies of race, ethnicity, and nation. As a result, their labor becomes as disposable as the waste they clean. Using this as a point of departure, the author identifies the exploitative agenda behind the universalising rhetoric of ‘civilisational feminism’, and calls for us to evolve a decolonised pedagogy for gender history, and women’s political thought, as a means to decolonise feminism. Moreover, she makes a compelling case for what she terms as ‘multidimensional’ feminism, which goes a step forward from existing discourses on intersectional feminism. This interview and this article both provide short overviews of her larger arguments.

In the interview she responds to the question: what does it mean to decolonise feminism?

“…(to decolonise feminism)…is to reclaim the forgotten and [hidden] history of racialised women’s fights. Women of colour are fighting not only for equal rights but also against exploitation, injustice, and oppression. Women in the Global South have always been in the front lines of feminist fights, yet their voices are never heard unless they’re instrumentalised. You have to uphold their voices, to read their material, to recenter their narratives.”

After this extremely thought provoking read, I found myself reflecting on the existing works of intellectual history which attempt this task of decolonising women’s political thought. What immediately came to mind was Milinda Banerjee’s monograph titled ‘The Mortal God: Imagining the Sovereign in Colonial India’. This subversive intellectual history of sovereignty provides a framework for decolonising political thought on one hand, by looking at vernacular registers of the idea in South Asia. On the other hand, the author looks at women’s discourses on sovereignty, and queenship, thereby foregrounding women’s voices in his non-Eurocentric conceptual exploration. There are two other works which attempt a similar task. These include the 2015 classic titled ‘Towards an Intellectual History of Black Women’, co-edited by Mia Bay, Farah J. Griffin, Martha S. Jones, and Barbara D. Savage; and secondly, the more recent volume titled ‘Women’s International Thought: A New History’ co-edited by Patricia Owens, and Katharina Reitzler. To say that Vergès’ book is inspiring and thought-provoking is utterly insufficient. It is a call to action. It is an invitation for us to formulate solidarities as we collectively seek to evolve decolonized anti-capitalist pedagogies of feminism and gender politics. On that note, next on my reading list is Sylvia Tamale’s Decolonization and Afro-Feminism, which recentres the concept of ubuntu as social justice, instead of the Eurocentric discourse on human rights, as the epistemic tool for uncovering the history of African women’s thought and activism. These works all bring to the fore voices and ideas of those women whom civilizational feminism had marginalised, and whose radicalism neoliberal capitalism had disciplined in its attempt to canonise women’s thought.

Jonathon Catlin

Since living in Berlin for the better part of the past two years, I have followed ongoing debates about Holocaust memory and antisemitism in Germany. The latest round of debates can be said to have begun May 17, 2019, when the German parliament voted to endorse a resolution calling on cities and states to withhold public funding from institutions, organizations, and individuals affiliated with the movement for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) toward Israel. In December, 2020, a letter jointly authored by the Weltoffenheit (world openness) GG 5.3 Initiative, which comprises the heads of many of Germany’s major cultural and academic institutions, denounced the resolution as “detrimental to the democratic public sphere” and warned of its negative impact on the free exchange of ideas. That same month, the Bundestag’s scientific service department ruled that the resolution was not legally binding, as it would violate the constitutionally protected right to freedom of expression. Nevertheless, the resolution left its mark and has been widely implemented. Some have claimed the resolution has led to “an expansive culture of fear and inquisition” in Germany, while one of Germany’s leading scholars of Holocaust memory, Aleida Assmann, proclaimed, “a spectre is haunting Europe: the accusation of antisemitism.” One month after the BDS resolution was passed, Peter Schäfer, a non-Jewish scholar, was forced to step down as director of Berlin’s Jewish Museum after the museum retweeted an article about a petition critical of the resolution signed by 240 Jewish studies scholars. About a year later, in April, 2020, the Cameroonian-born postcolonial philosopher Achille Mbembe, who had been invited to give the keynote lecture at the Ruhrtrienale culture festival, was charged with harboring antisemitic views, supporting BDS, and “relativising the Holocaust.” Germany’s federal commissioner for Jewish life and combating antisemitism, Felix Klein, called for Mbembe to be disinvited, but the festival was canceled due to the Covid-19 pandemic; in turn, hundreds of defenders of Mbembe from both African and Jewish/Israeli backgrounds signed petitions calling for the resignation of Klein and a restructuring or abolition of the new post he holds. The ensuing “Mbembe affair” in the summer of 2020 involved many of Germany’s leading intellectuals. It has reactivated older “Anxieties in Holocaust and Genocide Studies” concerning other genocides and colonialism. It is too soon to say how the debate will resolve and how its history will be written, but it has already been indexed in an English-language forum in the Journal of Genocide Research introduced by Dirk Moses and Ulrike Capdepón and featuring responses by leading scholars of history and memory, including Aleida Assmann, Natan Sznaider, Irit Dekel and Esra Özyürek, and Susan Neiman.

The debate has been mired with hostility, accusation, and defensiveness—especially in light of the latest conflict in Israel/Palestine—but it has also produced a number of important reflections, ranging from thoughtful to provocative, that are essential reading for anyone wishing to understand contemporary Holocaust memory and debates about antisemitism in Germany: Michael Rothberg’s “The Specters of Comparison” and “‘People with a Nazi Background’: Race, Memory, and Responsibility,” Rothberg and Jürgen Zimmerer’s “Enttabuisiert den Vergleich!” (Abolish the Taboo on Comparison!), Dirk Moses’s “The German Catechism,” and Fabian Wolff’s reflection on being Jewish in Germany, “Only in Germany.” The clash between these international or marginal thinkers and the mainstream German press has revealed a deep cultural rift and highlighted the historically understandable particularity (and provincialism) of German memory. As Sznaider noted, both sides of the debate have suffered from a tendency to universalize their particular point of view. A few years on from the launch of her book Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil, Susan Neiman, a Jewish-American public intellectual who has worked in Germany for many years as director of the Einstein Forum (to see how much has changed since the 1980s, read her memoir, Slow Fire: Jewish Notes from Berlin), reflected that in light of the latest debates her book may have been too praiseworthy about German society’s capacity of self-criticism and accepting responsibility. Having been called antisemitic for her role in organizing the Weltoffenheit initiative, she doubts whether such German-Jewish luminaries as Hannah Arendt or Albert Einstein would be allowed to speak in Germany today, given their criticisms of Israeli policies. “Caught in the shame of being descendants of the Nazis,” she writes, “some Germans find it easier to curse universalistic Jews as antisemites than to realize how many Jewish positions there are.”

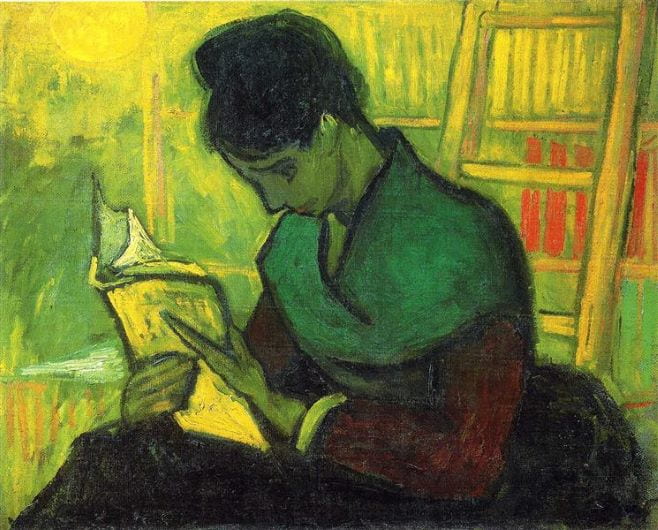

Featured Image: Vincent van Gogh, The Novel Reader. 1888. Courtesy of WikiArt.