by Oliver Weber

In order to stabilize the tumbling financial markets and maintain the liquidity of companies and states, central banks around the world responded to the Covid-19 pandemic by increasing the money supply. The public discussion about these fiscal and monetary decisions, from their sufficiency to their potential for triggering future inflation, are dominated by economists. The advice of political philosophers, meanwhile, especially those from centuries ago, is not particularly sought after.

Yet this was not always the case. From antiquity until well into the 19th century, European and North American political philosophy revolved around questions of state financing, debt, property, and money. In other words, the relationship between economics and politics was at the heart of the theoretical debate. As such, it was also central for Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who wrote the entry “Économie politique” for Diderot’s and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, corresponded with the Physiocrats, and had none other than Adam Smith attentively review parts of his discourse on inequality.

Today, Rousseau is best known for his advocacy of strong republican ideals, and his focus on the common will and personal presence of the people in contrast to the principle of representation that characterizes the modern, liberal organization of state and government. It is this Rousseau whom Jürgen Habermas famously criticized in Between Facts and Norms for overburdening citizens with demands for virtue and the common good. But when re-reading Rousseau’s works in the context of his time, it is striking that, much more so than political principles, economic considerations abound and place Rousseau at a great distance from our contemporary conditions.

In Rousseau’s mind, the Enlightenment thinkers, with whom he otherwise sided to considerable extent on political questions, articulated paradoxical economic and political demands. Montesquieu, for example, considered it his political task to revive ancient ideas of a free state, so that the freedom of citizens would no longer be threatened by royal and feudal despotism. But unlike their ancient predecessors, Enlightenment intellectuals no longer sought to organize this republicanization on the basis of the self-sufficient oikoi of an agrarian economy, but instead with the help of the modern opportunities of trade and manufacture. As Istvan Hont has noted, Rousseau turned against this idea of a commercial republicanism in the most resolute form.

In his Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau described how a society that accepted a liberalized economic sphere would also inevitably find itself in despotic political waters. Natural man’, who historically was in a harmonious balance with outer and inner nature in Rousseau’s formulation, became dangerously unbalanced when beginning to practice the division of labour, agriculture, and metallurgy. In this way, Rousseau made use of the dominant colonial discourses of his time, not to overturn them, but to reverse them: Instead of tracking progress from “savage” to “civilised” man, Rousseau told a story of human degeneration. According to him, an economy based on the division of labour meant nothing other than individuals no longer being able to provide for their own subsistence from their own resources and, as a consequence, becoming dependent on one another. “From the moment that one man needed the help of another […] equality disappeared, property arose, labour became necessary” (OC III, p. 171). And this mutual dependence was never symmetric: instead, talents, skill, diligence, and physical abilities inevitably caused differences in property and conduct, such that social inequality arose. Having become dependent on his fellow men, a once ‘natural’ man could thus only relate to himself by way of relating to others, which deepened the state of interdependence.

Over time, Rousseau reasoned, the poor thus became dependent on being paid by the rich or on robbing them, and the rich became dependent on the poor remaining dependent. Conflicts would then arise within society. In his reading, this socialized state perpetually threatened to bring about the Hobbesian war of all against all (45), which was only half-heartedly prevented by the introduction of formal equality before the law, even if only in order to make economic inequality permanent. But such a state is destined to slide down the same slippery slope as society already did: lawbreakers made magistrates necessary, which in turn necessitated elections, elections required political parties, these provoked civil wars, from which followed perpetual dictatorship and, finally, despotism. In essence, Rousseau’s message to his Enlightenment contemporaries was that no republic could be built on the basis of asymmetrical economic interdependence — and to him, trade, division of labor and money regimes were just that.

In so arguing, Rousseau wrote explicitly against the major political-economic theories of his time: against the physiocrats, against mercantilist ideas, but above all against Montesquieu’s idea that trade and commerce brought about a liberalization and pacification of the political sphere—an idea that would inspire James Denham-Steuart, John Millar, David Hume and, later on, Adam Smith. Montesquieu reasoned that modern commerce and manufactures made citizens independent of their rulers. If these rulers transgressed the limits of civic consent, one could easily withdraw one’s possessions, mobile capital or even money from the grasp of the crown. This threat to the control exercised by monarchy and feudal nobility automatically limited governmental power. Adam Smith thought along similar lines and expanded this argument: If cleverly managed, he wrote, even the rulers’ exorbitant claims to luxury and consumption could be used to create work and prosperity and, at the same time, bring about the rule of law. According to him, the complexity of flourishing trade in the cities and the growth of mutual interdependence overwhelmed the power that despots could muster to govern. With this, Montesquieu (like Smith later) turned against absolute monarchy from the outside, i.e. politically, in order to discipline it from the inside, i.e. economically.

Rousseau, however, turned these arguments against their proponents. His discussion of political economy in the Second Discourse was precisely aimed at showing that what Montesquieu and Smith considered the disciplinary threat that citizens posed to their monarchs would turn into a disciplinary order that benefits the rich at the expense of the republic. For Rousseau, economic inequality, asymmetric economic interdependencies, and private interests prevented the formation of a common will. Therefore, it was perfectly consistent to him that, just as there should be no partisanship in the political world, the republic must presuppose the material self-sufficiency of its citizens. Thus, he ordered in the Contrat social that no citizen of his ideal republic should be “so wealthy as to be able to buy another, and none so poor as to be forced to sell himself” (OC III, p. 391). Notably, this seemingly economic argument was premised on a political observation: the rich and the poor were equally dangerous to the common good, “from the one come the abettors of tyranny, from the other the tyrants; the trade in public liberty is always between them; the one buys and the other sells it” (OC III, p. 392).

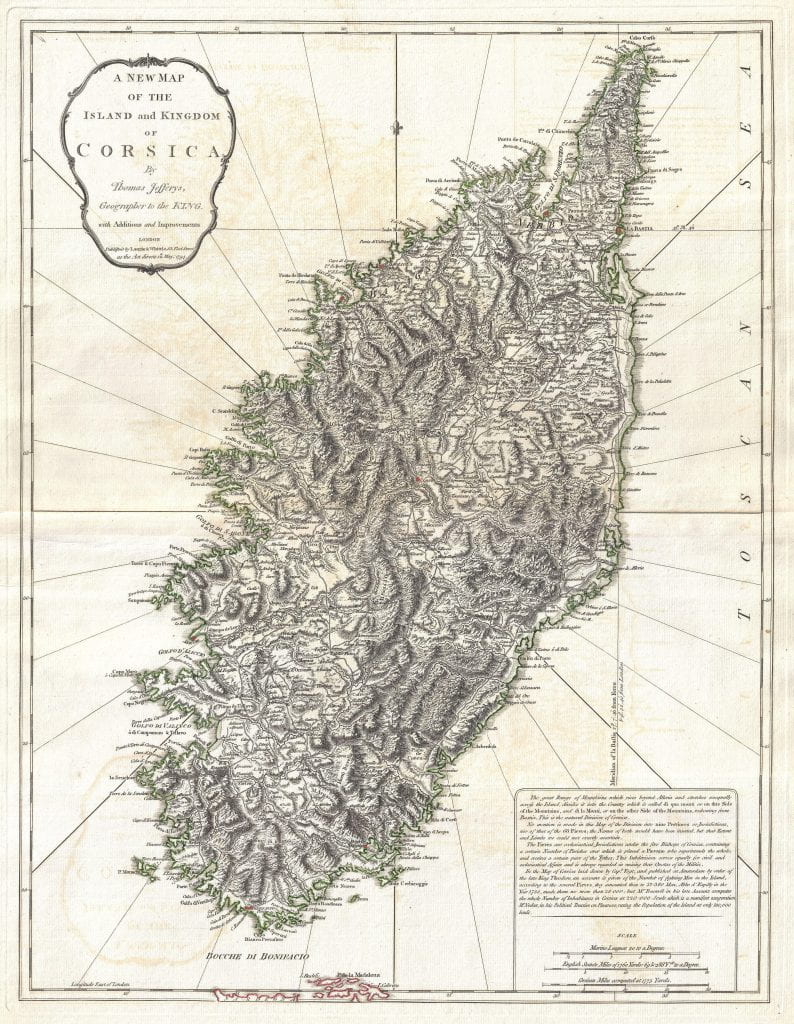

However, anyone who thinks that Rousseau considered himself utopian is mistaken. Already in the Contrat social, he praised Corsica as one of the few exceptions that, under the historical conditions of his time, would still be capable of forming a republic along the lines he set forth — not least because, in the eyes of Rousseau, Corsicans appeared uncivilized. After the latter had made some gains in the fight for Corsican independence, Matteo Buttafuoco approached Rousseau in 1764 with the request to draft a constitution for Corsica. Rousseau enthusiastically agreed. Interestingly, his proposed constitution, which survived through his estate, is largely devoted to the economic rather than the political situation in Corsica. Rousseau recommended, for example, that a prerequisite for citizenship should be the possession of sufficient land to provide for oneself and one’s family, and so that the asymmetrical dependence described in the Second Discourse would not occur. Rousseau believed that there was enough territory available in Corsica to allow every inhabitant to own farmland.

But Rousseau knew, of course, how far modern conditions had advanced in comparison to antiquity. Large empires in the island’s geographical neighborhood, monetary and fiscal systems, trade, and manufactures were obstacles to the peaceful republicanization of the Corsicans. Rousseau’s response to these unfavorable conditions was as radical as it was consequential: limited foreign trade to prevent a dependence on neighboring territories, hardly any internal trade in order to conserve the independence of citizens from one another, and a requirement that manufacturers and craftsmen had to settle far away from the trading places to make their businesses costly and burdensome. Expressed in modern economic vocabulary: Rousseau tried to internalize the politically external costs of the economy—for the good of the republic.

It was the financial and monetary system that worried Rousseau the most. The virtualization of goods in the form of money provided the conditions for a limitless accumulation of wealth and thus disconnection from the polity. Money — although supplied and guaranteed for by the state — could become a vehicle for particular interests and, in the last consequence, for anti-republican developments. Therefore, according to Rousseau, money was to be kept to a minimum in Corsica and to be replaced as far as possible by a local barter economy that was to be administered by the state: “In a truly free state, citizens do everything on their own and nothing with money” (OC III, p. 439). Taxes should also be possible in kind and supplemented by the state itself, i.e. state property that yields revenue for the payment of the magistrates. Only in the extreme, and only if direct exchange is impossible, Rousseau considered the use of a currency to serve as a unit of account (he suggests pistols as a basis). The fiscal administration of Corsica therefore had, in Rousseau’s plan, the enormously important task of keeping an eye on how the relationship between the circulation of abstract money and the concrete barter developed, in order to be able to counteract possible aberrations, such as those described in the Second Discourse. The Rousseauan citizens of Corsica were to be protected from their own self-interest by the constitution, which instituted and regulated the legal and monetary systems through which citizens could interact in such a way that the independence of the republic would be preserved, both internally and externally.

Rousseau’s considerations for Corsica sound very distant today. Since the 19th century, the economic developments that Rousseau could still observe in their early stages – the development of markets, the emergence of the division of labor, the flourishing of trade and industry, the introduction of taxes and monetary regimes – have fully taken hold and determine our present. But perhaps Rousseau’s warning about the paradoxes of a politically and economically free society can help us better understand today’s problems. The difficulty of present-day democracies, as was already evident in the financial crisis and has now again has come to the fore during the pandemic, is that they are in many ways dependent on developments in their economic foundation: citizens are dependent on their jobs, on international markets, on capital inflows and outflows; the state is dependent on tax revenues, on the confidence of financial markets, and on the status of its social security systems. Rousseau’s vision of an economically self-sufficient citizenry and republic is more than elusive — but the problems it was meant to counteract can be felt everywhere.

Perhaps a virtue can be made of necessity? Rousseau’s strong aversion to the money form was fed by the fact that monetary wealth is based on the possession of collectively guaranteed symbols. This makes the owners of large sums of money predominantly independent from the polity’s requirements of virtue and subsistence: they can simply escape the requirements by moving their possessions elsewhere. This was Rousseau’s criticism of the advocates of doux commerce like Montesquieu. But are the rich not simultaneously dependent on the politics of the community? The value of their wealth is based entirely on the state’s guarantee that they will one day be able to convert their symbols into goods and labor, because without common trust in the value of money that the state embodies and guarantees, monetary wealth vanishes. With the release of money, which the state usually delegates to its central bank, the republic has dangerously disconnected its citizenry from itself — in this Rousseau is completely right. But by reserving the sovereignty to determine the quantity, the interest rate, i.e. ultimately the value of money, the state can attempt to return the circulating monetary wealth to republican purposes. That the money supply is not an apolitical quantity is very clearly demonstrated by the actions of central banks during the present pandemic. Perhaps this is where a modern political theory, economically up-to-date, would have to start in order to examine and help preserve the economic conditions of democratic self-government.

Oliver Weber is a Master’s student of democratic studies at the University of Regensburg, Germany. He is mainly interested in the political theory of republican orders and their economic conditions of maintenance. He tweets @OliverBWeber.

Featured Image: Jean-Jacques Rousseau commemorative medal (bronze Galvano). Courtesy of Tulane University Digital Library, B. Bernard Weinstein Medal Collection.