By guest contributor Joshua Fogel

Several years ago, I was invited to give a paper at a workshop organized by graduate students at University of California, Berkeley. The topic was friendship in East Asia—with no specified time period or country or discipline. I have worked in the field of the cultural relations between Chinese and Japanese for several decades now, and I have long been intrigued by the friendship between the two men given in my title—the former China’s best-known writer of the twentieth century and the latter the Japanese owner of a bookstore in Shanghai, who lived in China for thirty years. I knew something of their ties, but this invitation gave me an opportunity to plunge into it head-first. The workshop did not produce a volume of proceedings, but I continued with my paper and came up with a short book published earlier this year (2019) by the Association for Asian Studies in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Lu Xun was one of the best-educated men of his era, a thoroughgoing iconoclast in many realms and, at the same time, a man deeply attached to many of his own cultural traditions. He managed to alienate almost all of the political types who came into contact with him—Communist or Nationalist—because he simply couldn’t abide empty slogans and did not suffer fools, and he was a virtual magnet for young writers and artists, and of course journalists. He was an open Japanophile (culturally, not politically) at a time when that was anything but politically correct, and mercilessly critical of countless aspects of Chinese behavior. The Communists have adopted him (posthumously, of course), although in the 1930s they attacked him pitilessly; since his death (when he no longer had the capacity to affect his image), he has become an icon in China and the center of a publishing cottage industry, with journals, and schools, and parks, and museums named after him. In fact, for the longest time, he was for Western Sinology the only twentieth-century Chinese writer worthy of more than one book. I never dreamed that I might add to that section of the library.

Meanwhile, across the Yellow Sea, Uchiyama dropped out of school at age twelve, held a number of menial dead-end jobs, and then found God, converted to Christianity, and became a traveling salesman in the Lower Yangzi region on the Chinese Mainland. Somehow, he acquired sufficient Chinese to do this and then with his wife opened a bookstore in Shanghai in the late 1910s. The store grew and grew until it held the largest collection of Japanese books in the city. This was a time when thousands of Chinese who had earlier studied in Japan and returned home were now trying to keep abreast of the world, and doing so via Japanese publications and translations was the means of choice. They flocked to Uchiyama’s bookstore and made it a success.

Lu Xun showed up several days after moving to Shanghai in 1927, and the two men—despite their entirely different backgrounds—hit it off immediately and became the closest of friends. As the political world of Shanghai was closing in on Lu Xun—there were several attempts on his life—Uchiyama repeatedly found safe houses for him and his family to relocate to, including the second story of his own store. He also handled all of Lu Xun’s mail and royalties through the bookstore—which also meant that Lu Xun’s address would not be public knowledge. When Lu Xun tried to popularize Chinese woodcuts, a project which became extremely important to him, on several occasions Uchiyama found space in the city for exhibitions and even imported his brother from Tokyo to teach the craft to Chinese students. Woodcuts were an ancient Chinese art (or craft), but the technique had largely been forgotten in the country.

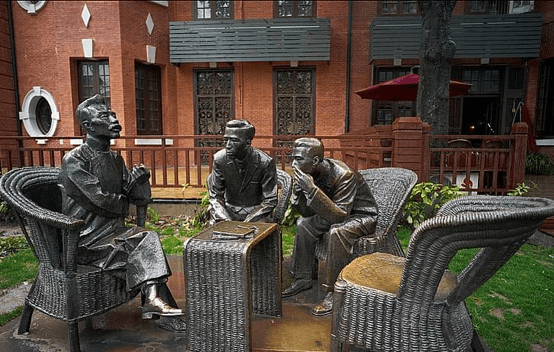

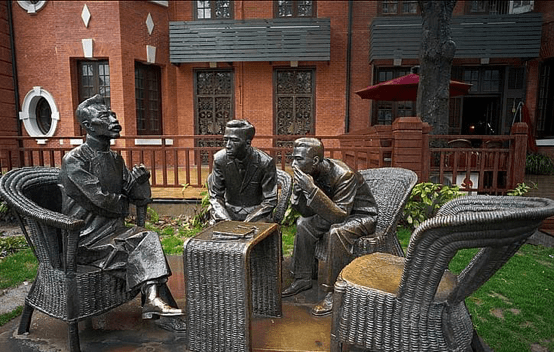

Under normal circumstances, Lu Xun would appear every day at the Uchiyama Bookstore and spend hours “holding court” with younger writers and journalists, smoking non-stop—in fact, there was a special rattan chair that Uchiyama placed in the bookstore which everyone knew was reserved for Lu Xun. Tea and sweets were always in served by the Uchiyamas, especially in wintertime.

His daily presence rendered the bookstore a kind of latter-day salon, and his followers constituted a who’s who of Chinese culture.

My book follows the friendship between these two men, how they helped each other, and what each may have gained from the other’s friendship. Friendship is a difficult concept about which to generalize—being culturally, temporally, and personally bound in so many ways. Nonetheless, Uchiyama provided Lu Xun with a safe space in his bookstore where he could meet and converse with dozens and dozens of Chinese and Japanese poets, novelists, screenwriters, publishers, artists of all stripes, and many others, a space relatively free of fractious political world outside. And, he could smoke (in the bookstore!) to his heart’s content. It was Lu Xun’s happiest place, other than his home, to spend time over the last decade of his life. Uchiyama, of course, looked up to Lu Xun, as did almost everyone in the cultural world of Shanghai. He also arranged an assortment of meetings between Lu Xun and Japanese publishing houses—and even with visiting dignitaries, such as George Bernard Shaw.

Lu Xun’s chain-smoking caught up with him in 1936, while Uchiyama lived another twenty-plus years before suddenly succumbing to a heart attack while on a visit to China. He is buried in the international cemetery in Beijing. Writing this book over the past few years has thrown into relief just how hard it can be for people with totally different backgrounds, nationalities, religions, and politics to remain friends. If anything, it was probably harder in Shanghai in the late 1920s and 1930s, as total war was soon to engulf the region; one year after Lu Xun’s death, the Japanese military launched an attack on Shanghai. That same year, on the anniversary of his death, Mao Zedong (then hiding in the caves of far-off Yan’an) wrote a eulogy for the man he dubbed a “sage” (shengren). I’m sure Lu Xun is still turning in his grave.

Joshua Fogel holds a Canada Research Chair in history at York University, and is the author of numerous books, most recently A Friend in Deed: Lu Xun, Uchiyama Kanzō, and the Intellectual World of Shanghai on the Eve of War (Ann Arbor: Association for Asian Studies, 2019).

Leave a Reply