By guest contributor Jacob Romanow

When people call a book “melodramatic,” they usually mean it as an insult. Melodrama is histrionic, implausible, and (therefore) artistically subpar—a reviewer might use the term to suggest that serious readers look elsewhere. Victorian novels, on the other hand, have come to be seen as an irreproachably “high” form of art, part of a “great tradition” of realistic fiction beloved by stodgy traditionalists: books that people praise but don’t read. But in fact, the nineteenth-century British novel and the stage melodrama that provided the century’s most popular form of entertainment were inextricably intertwined. The historical reality is that the two forms have been linked from the beginning: in fact, many of the greatest Victorian novels are prose melodramas themselves. But from the Victorian period on down, critics, readers, and novelists have waged a campaign of distinctions and distractions aimed at disguising and denying the melodramatic presence in novelistic forms. The same process that canonized what were once massively popular novels as sanctified examples of high art scoured those novels of their melodramatic contexts, leaving our understanding of their lineage and formation incomplete. It’s commonly claimed that the Victorian novel was the last time “popular” and “high” art were unified in a single body of work. But the case of the Victorian novel reveals the limitations of constructed, motivated narratives of cultural development. Victorian fiction was massively popular, absolutely—popularity rested in significant part on the presence of “low” melodrama around and within those classic works.

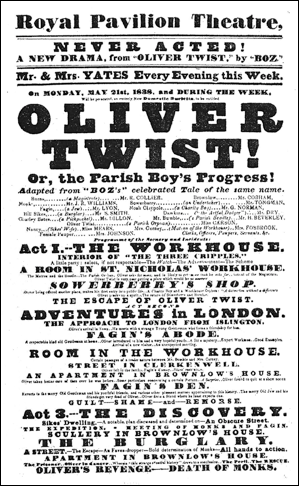

A poster of the dramatization of Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist

Even today, thinking about Victorian fiction as a melodramatic tradition cuts against many accepted narratives of genre and periodization; although most scholars will readily concede that melodrama significantly influences the novelistic tradition (sometimes to the latter’s detriment), it is typically treated as an external tradition whose features are being borrowed (or else as an alien encroaching upon the rightful preserve of a naturalistic “real”). Melodrama first arose in France around the French Revolution and quickly spread throughout Europe; A Tale of Mystery, an uncredited translation from French considered the first English melodrama, appeared in 1802 (by Thomas Holcroft, himself a novelist). By the accession of Victoria in 1837, it had long been the dominant form on the English stage. Yet major critics have uncovered melodramatic method to be fundamental to the work of almost every major nineteenth-century novelist, from George Eliot to Henry James to Elizabeth Gaskell to (especially) Charles Dickens, often treating these discoveries as particular to the author in question. Moreover, the practical relationship between the novel and melodrama in Victorian Britain helped define both genres. Novelists like Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Thomas Hardy, and Mary Elizabeth Braddon, among others, were themselves playwrights of stage melodramas. But the most common connection, like film adaptations today, was the widespread “melodramatization” of popular novels for the stage. Blockbuster melodramatic productions were adapted from not only popular crime novels of the Newgate and sensation schools like Jack Sheppard, The Woman in White, Lady Audley’s Secret, and East Lynne, but also from canonical works including David Copperfield, Jane Eyre, Rob Roy, The Heart of Midlothian, Mary Barton, A Christmas Carol, Frankenstein, Vanity Fair, and countless others, often in multiple productions for each. In addition to so many major novels being adapted into melodramas, many major melodramas were themselves adaptations of more or less prominent novels, for example Planché’s The Vampire (1820), Moncrieff’s The Lear of Private Life (1820), and Webster’s Paul Clifford (1832). As in any process of adaptation, the stage and print versions of each of these narratives differ in significant ways. But the interplay between the two forms was both widespread and fully baked into the generic expectations of the novel; the profusion of adaptation, with or without an author’s consent, makes clear that melodramatic elements in the novel were not merely incidental borrowings. In fact, melodramatic adaptation played a key role in the success of some of the period’s most celebrated novels. Dickens’s Oliver Twist, for instance, was dramatized even before its serialized publication was complete! And the significant rate of illiteracy among melodrama’s audiences meant that for novelists like Dickens or Walter Scott, the melodramatic stage could often serve as the only point of contact with a large swath of the public. As critic Emily Allen aptly writes: “melodrama was not only the backbone of Victorian theatre by midcentury, but also of the novel.”

This question of audience helps explain why melodrama has been separated out of our understanding of the novelistic tradition. Melodrama proper was always “low” culture, associated with its economically lower-class and often illiterate audiences in a society that tended to associate the theatre with lax morality. Nationalistic sneers at the French origins of melodrama played a role as well, as did the Victorian sense that true art should be permanent and eternal, in contrast to the spectacular but transient visual effects of the melodramatic stage. And like so many “low” forms throughout history, melodrama’s transformation of “higher” forms was actively denied even while it took place. Victorian critics, particularly those of a conservative bent, would often actively deny melodramatic tendencies in novelists whom they chose to praise. In the London Quarterly Review’s 1864 eulogy “Thackeray and Modern Fiction,” for example, the anonymous reviewer writes that “If we compare the works of Thackeray or Dickens with those which at present win the favour of novel-readers, we cannot fail to be struck by the very marked degeneracy.” The latter, the reviewer argues, tend towards the sensational and immoral, and should be approached with a “sentiment of horror”; the former, on the other hand, are marked by their “good morals and correct taste.” This is revisionary literary history, and one of its revisions (I think we can even say the point of its revisions) is to eradicate melodrama from the historical narrative of great Victorian novels. The reviewer praises Thackeray’s “efforts to counteract the morbid tendencies of such books as Bulwer’s Eugene Aram and Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard,” ignoring Thackeray’s classification of Oliver Twist alongside those prominent Newgate melodramas. The melodramatic quality of Thackeray’s own fiction (not to mention the highly questionable “morality” of novels like Vanity Fair and Barry Lyndon), let alone the proactively melodramatic Dickens, is downplayed or denied outright. And although the review offers qualified praise of Henry Fielding as a literary ancestor of Thackeray, it ignores their melodramatic relative Walter Scott. The review, then, is not just a document of midcentury mainstream anti-theatricality, but also a document that provides real insight into how critics worked to solidify an antitheatrical novelistic canon.

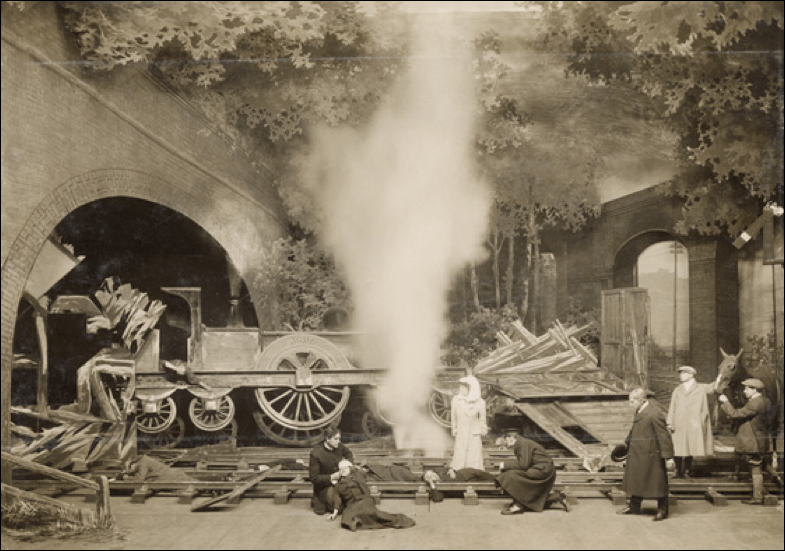

Photographic print of Act 3, Scene 6 from The Whip, Drury Lane Theatre, 1909

Gabrielle Enthoven Collection, Museum number: S.211-2016

© Victoria and Albert Museum

Yet even after these very Victorian reasons have fallen aside, the wall of separation between novels and melodrama has been maintained. Why? In closing, I’ll speculate about a few possible reasons. One is that Victorian critics’ division became a self-fulfilling prophecy in the history of the novel, bifurcating the form into melodramatic “low” and self-consciously anti-melodramatic “high” genres. Another is that applying historical revisionism to the novel in this way only mirrored and reinforced a consistent fact of melodrama’s theatrical criticism, which too has consistently used “melodrama” derogatorily, persistently differentiating the melodramas of which it approved from “the old melodrama”—a dynamic that took root even before any melodrama was legitimately “old.” A third factor is surely the rise of so-called dramatic realism, and the ensuing denialism of melodrama’s role in the theatrical tradition. And a final reason, I think, is that we may still wish to relegate melodrama to the stage (or the television serial) because we are not really comfortable with the roles that it plays in our own world: in our culture, in our politics, and even in our visions for our own lives. When we recognize the presence of melodrama in the “great tradition” of novels, we will better be able to understand those texts. And letting ourselves find melodrama there may also help us find it in the many other parts of plain sight where it’s hiding.

Jacob Romanow is a Ph.D. student in English at Rutgers University. His research focuses on the novel and narratology in Victorian literature, with a particular interest in questions of influence, genre, and privacy.

Leave a Reply