by guest contributor Elizabeth Everton

In a 2009 interview, Twitter’s founder, Jack Dorsey, drew upon the dictionary definition of “tweet” – “a short burst of inconsequential information” – to characterize his creation. Ten years after Twitter’s inception, few would persist in dismissing it as inconsequential; from the Arab Spring to Occupy and Black Lives Matter, the degree to which political and social movements thrive on social media is clear. Yet politics has always existed on the margins – dominant discourses have always been baited by smaller counter-discourses, composed not only of grand speeches but maddening collections of inconsequential information.

One legacy of the Dreyfus Affair is a welter of words, from Emile Zola’s justly famous “J’Accuse” to the hundreds of works of non-fiction and fiction inspired by the case. The Affair also produced innumerable bursts of inconsequence, in the form of signatures on petitions and manifestos; letters, such as the 2000+ sent to Alfred and Lucie Dreyfus; postcards and songs, stickers and cigarette rolling papers; and names published in newspapers, intended to expose (lists of Jewish officers in the French military) or extol (lists of members of newly founded leagues). And perhaps the most infamous, the Henry Subscription, the “Golden Book” of anti-Dreyfusism, the list of names and messages published between December 1898 and January 1899 in the anti-Jewish newspaper La Libre Parole.

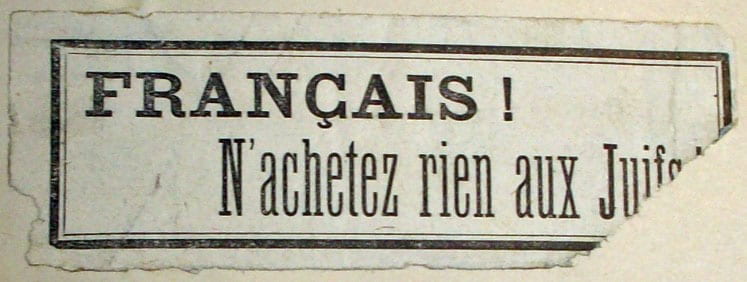

Sticker, “Français! N’achetez rien aux Juifs!” (Archives Nationales de France, 1898/1899)

The origins of the Henry Subscription lie in the byzantine efforts of the French Intelligence Bureau to block the reopening of the Dreyfus case, specifically the retroactive proof of Dreyfus’s guilt forged by Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Henry in 1896. Produced to the right people at the right time – that is, military and civilian officials casting about for reasons not to look further – this document seemed to settle the case until “J’Accuse” cracked it open in January 1898. Reexamined under electric light, the forgery was discovered and its creator questioned and arrested. The next day, Henry committed suicide.

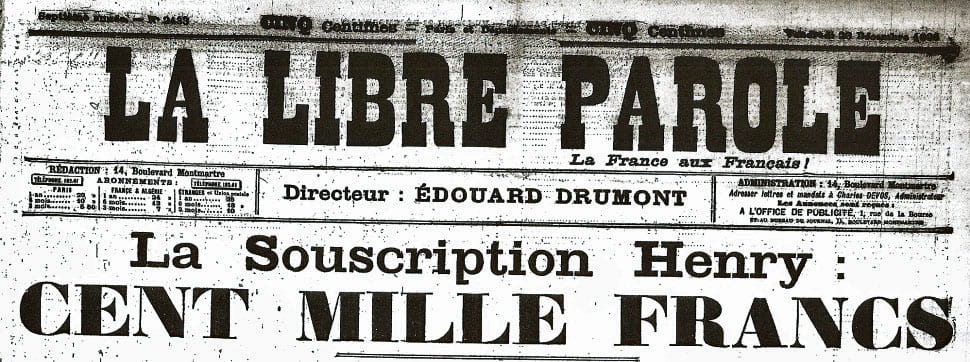

For Dreyfus’s supporters, this was proof not only of Henry’s guilt but Dreyfus’s innocence. Historian Joseph Reinach, one of the foremost Dreyfusards, published a series of articles arguing that Henry had colluded in the treason for which Dreyfus was convicted. Henry’s widow Berthe protested, bringing a suit for defamation. La Libre Parole, an adversary of the Jewish Reinach, called upon the “good folk” of France to send money to pay the widow’s legal bills. The subscription drive started on December 14, 1898; by the time it wrapped up on January 15, 1899, over 130,000 francs had been raised from about 20,000 donations. During the drive, La Libre Parole published subscriber names and messages, thousands upon thousands of them, a window into the identity and attitudes of the donors and, by extension, the anti-Dreyfusard movement.

Masthead advertising Henry Subscription (La Libre Parole, 23 December 1898)

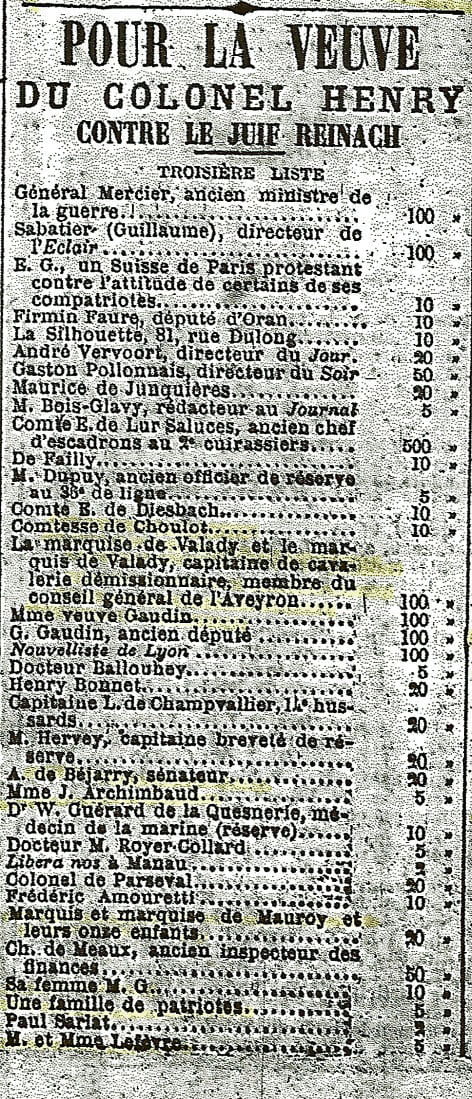

Dreyfusards and anti-Dreyfusards alike immediately identified the Henry Subscription as a watershed. In 1899, Dreyfusard Pierre Quillard published a compilation of subscription entries organized by profession, social status, and attitudes expressed in messages. For Quillard, the Henry Subscription represented an outpouring of anti-Semitism, inflected with militarism and clericalism; his goals in compiling and publishing the entries were to name and shame subscribers and reveal the latent hatred at the subscription’s core. Historians studying the Henry Subscription tend to use this compilation – the original submissions being long gone and the published lists published unwieldy – but in so doing, they unconsciously reproduce Quillard’s Dreyfusard perspective. There is no question that many subscribers and messages were anti-Semitic; it was, after all, published in an anti-Semitic newspaper with the tagline “for the widow Henry against the Jew Reinach.” But the Quillard compilation decontextualizes the lists and imposes a new ordering system defined by a Dreyfusard interpretive framework exterior to the subscription itself. For Quillard, the individual messages, excepting those that particularly reflect this whole, are unimportant –so many bursts of inconsequential information. This epistemological framework, in the end, obscures the perspective of the milieu that created the lists: the anti-Dreyfusards.

Excerpt from the third list of the Henry Subscription (La Libre Parole, 16 December 1898)

Let us look again at these messages. The Henry Subscription as monument fades away, to be superseded by an image of the subscription as a work in progress, a collective project undertaken though the collaboration of thousands of subscribers, guided by the active intervention of the editors of La Libre Parole. The first aspect of the subscription to be recovered is their temporal dimension. The Henry Subscription lists existed not only to put anti-Dreyfusard attitudes on display but also to inspire further subscriptions, to be published on subsequent days. This encouragement came not only from La Libre Parole but from the subscribers themselves, such as a December 15, 1898, message scolding of the Minister of War for not having subscribed. These sorts of appeals did not go unheard or unremarked; the name of General Mercier, the former Minister of War who engineered Dreyfus’s arrest and conviction, appeared at the head of the December 16 list.

What we see with the Henry Subscription, then, is a complex form of multidirectional communicative exchange. It functioned as a public site where subscribers could communicate with the newspaper, with each other, with non-subscribing readers, and with those involved in the anti-Dreyfusard movement more broadly. These communications ranged from the generic – the first message printed was an uncontroversial “for the love of France and its army” – to the surprisingly personal, including expressions of anger, sorrow, and shame. Subscribers published these messages with the expectation that they would be read, and so they were.

Meaning can and should be found not only in the content of the lists but in their construction. I suggest that the Henry Subscription can be read as a project akin to the Enlightenment Republic of Letters as expounded upon by Dena Goodman: a system of reciprocal exchanges working towards a common Enlightenment project, out of which emerges an oppositional public sphere. Drawing a connection between the Henry Subscription and the Enlightenment Republic of Letters seems absurd, given the disdain many anti-Dreyfusards felt for the legacy and values of the Enlightenment. But similarities exist nonetheless, in its collective, collaborative nature and creation of an oppositional counter-state. Few observers in 2016 can be surprised that counter-discourses and the technologies that amplify them need not be progressive. La Libre Parole described the lists as a “patriotic hodgepodge” in which people of all ages, genders, professions, and walks of life could rub shoulders. The only commonality was their membership in the true nation, a sort of anti-Dreyfusard silent majority given voice by the subscription. But the lists pose a conundrum. For the anti-Dreyfusards, the nation was rooted in ethno-nationalist concepts of identity that excluded religious minorities and those identified as “foreign,” in sharp contrast to the assimilationist republic. We find in the lists, however, contributions from foreign nationals, from Protestants, and even from Jews. In sending money and publishing their message, subscribers of all backgrounds could stake their claim in the nation. To admire Madame Henry or the army, to denigrate Reinach and the Dreyfusards – these actions placed one within the “patriotic hodgepodge.” Membership in the true nation, writ small in the lists of the Henry Subscription, can therefore be seen as not only a function of ethnicity but also of action. Further examination of this document may reveal even more cracks in the seemingly solid veneer of the anti-Dreyfusard nation, not to mention the power of new technologies to shape or even create public spheres.

Lest the interviewer be fooled by his description of tweets as inconsequential, Jack Dorsey expanded upon his statement, explaining “bird chirps sound meaningless to us, but meaning is applied by other birds. The same is true of Twitter: a lot of messages can be seen as completely useless and meaningless, but it’s entirely dependent on the recipient.” What was true of Twitter in 2009 was true of the Henry subscription 110 years earlier and is true of other dribs and drabs of text that accumulate around political events. Like the messages of the Henry Subscription, these texts may be partial, adulterated, or untrustworthy in various ways; in listening to them, we are as much at the mercy of their creators as we are with any other work. Yet they can and should still be heard. The language of birds may be obscure, but it is not incomprehensible; with patience, these words too can be understood.

Elizabeth Everton is an independent scholar living in Charlotte, NC. She has a PhD in history from UCLA. She is currently working on a manuscript titled National Heroines: Women and the Radical Right during the Dreyfus Affair.

3 Pingbacks