by Chris O’Kane

The 100th anniversary of the founding of the Institute for Social Research (ISR) has led to a multitude of celebrations and reflections on Frankfurt School Critical Theory by prominent Critical Theorists at Critical Theory conferences and in Critical Theory Journals in the Anglophone world. In what follows, I focus on William Scheuerman’s and Samuel Moyn’s recently published short commentaries criticizing contemporary Frankfurt School Critical Theory for not focusing on the political economic dimensions of contemporary capitalism.

Scheuerman’s and Moyn’s criticisms are largely right when it comes to what is defined as Frankfurt School Critical Theory in the Anglophone world today (what Scheuerman rightly calls “Habermasian Critical Theory”). Yet, in what follows, I show that Scheuerman’s and Moyn’s comments are not accurate for Anglophone work that should be considered Frankfurt School Critical Theory.

In the space that permits, I first provide an outline of Scheuerman’s and Moyn’s criticisms of contemporary Frankfurt School Critical Theory. I then contextualize the emergence of the predominant understanding of the development of Frankfurt School Critical Theory into Habermasian Critical Theory in the Anglophone world alongside the development and marginalization of two subterranean lines of Frankfurt School Critical Theory, that drew on and developed what they saw as Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno’s relationship to Marxism and political economy.

I then provide an overview of recent work in political economy that has drawn on and expanded these subterranean understandings of the Frankfurt School in the areas that Moyn and Scheuerman indicate contemporary critical theory should take up. I conclude with a plea that these contributions be taken seriously as Frankfurt School Critical Theory, lest it be eclipsed.

I

Scheuerman’s commentary focuses on the historical moment he holds responsible for establishing the longstanding “lacuna” between Frankfurt School critical theory and political economy: the “marginalization” of political economy that was the unintended consequence of Friedrich Pollock’s theory of state capitalism. Appealing “to those already familiar with the history of the Frankfurt School” and Helmut Dubiel’s 1975 introduction to a collection of Pollock essays on stages of capitalism, Scheuerman contends that Pollock’s theory exemplified the “rigorous empirical research” in political economy that was “pivotal” “to the theoretically motivated interdisciplinary research” the ISR carried out at the time. Yet Pollock’s theory—which argued that the political power of state capitalism has overcome liberal capitalism’s economic contradictions—unintentionally provided Horkheimer and Adorno with a “political economy justification” to “sideline” political economy and “marginalize” other political economists (notably Franz Neumann) at the ISR. Because Horkheimer’s and Adorno’s ensuing work was based on Pollock’s theory, political economy “became marginal to postwar Frankfurt theory.” Consequently, this “troublesome legacy” was continued by “Habermasian Critical Theory” and “remains a problem” to this day. Contemporary Frankfurt School critical theorists do not draw on political economy and contemporary Frankfurt School critical theory has minimal impact on “empirically minded social scientists.” According to Scheuerman, the “result is a serious theoretical and political lacuna: without a proper political economy of contemporary capitalism, there can be no critical theory of society.”

Similarly concerned about contemporary Critical Theory’s supposed neglect of central political economic questions, Moyn’s commentary focuses on how the “stewards of critical theory” from the 1968 generation abandoned (neo)-Marxism and socialism for liberal cosmopolitan neo-Kantian constitutionalism. This led contemporary Frankfurt School Critical Theory to ignore critical issues such as neoliberalism, inequality, the war on terror, the unipolar post-cold war international system, democratic socialism’s vision of reform, and the rise of neo-fascism. Consequently, younger generations have turned to economistic and materialist conceptions of Marxism instead of Frankfurt School Critical Theory, thus putting the future of the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory in peril.

II

As Scheuerman and Moyn indicate, in the Anglophone world today, the predominant conception about the development of Frankfurt School Critical Theory into Habermasian Critical Theory resembles the whiggish “great man” approaches to the history of monarchical states. In this lens, Frankfurt School Critical Theory is treated as a scepter passed from the head figure of one generation to the next. The great ruler who modernized the kingdom—Jürgen Habermas—is seen as the pivotal historical figure who established the subsequent march of progress. His courtiers and successors further his progressive vision.

As Scheuerman and Moyn further indicate, the story goes something like this: while the ISR under Horkheimer founded critical theory as an interdisciplinary emancipatory enterprise that linked normative Western Marxist philosophy to real world socio-economic dynamics discerned by political economic research, Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment and their subsequent work moved away from Marx, political economy, and empirical social research for a totalizing, one-dimensional social theory of instrumental reason within state capitalist society that abandoned emancipatory theory for apolitical pessimism. To maneuver Critical Theory out of its purported conceptual and political cul-de-sac, Habermas developed a multidimension social theory and an emancipatory intersubjective notion of democratic practice, which was then deepened by Habermas’s successor Axel Honneth and others. The notion of Critical Theory developed by Habermas, Honneth, and the scholars who deepen their work is what is considered Frankfurt School Critical Theory today.

It is this conception of the Frankfurt School and its move away from (neo)-Marxism, political economy, and socialism to liberal cosmpolitianism neo-Kantian constitutionalism that Moyn and Scheuerman presciently criticize. However, although this Habermasian conception of the development of Frankfurt School Critical Theory is now predominant in the Anglophone world, it was not always so.

As Robert Zwarg’s history of the Critical Theory in America indicates, the reception of Frankfurt School Critical Theory in the Anglophone world occurred in the early 1970s in the context of the crisis of the New Left. What is notable about this period is that the aforementioned interpretations of Horkheimer and Adorno’s late critical theory that became the rationale for the predominant account of the development of Frankfurt School Critical Theory into Habermasian Critical Theory were contested. Traditions of Critical Theory that drew on what they saw as Marcuse’s, Horkheimer’s and Adorno’s approach to Marx’s Critique of Political Economy also developed alongside and against Habermasian Critical Theory. Indeed, it was not until the late 1970s and 1980s, that Habermasian Critical Theory became hegemonic, obscuring these subterranean traditions of “Frankfurt School Critical Theory.” Consequently, modern work in these traditions of critical theory in the areas Scheuerman and Moyn indicate are lacking in Habermasian Critical Theory are not considered to be Frankfurt School Critical Theory.

The aforementioned, monarchical hegemonic narrative about the evolution of Horkheimer and Adorno’s work away from the critique of political economy to the critique of instrumental reason, was first established in English by Albrecht Wellmer in 1971 and amplified in Martin Jay’s immensely influential Dialectical Imagination in 1973 (which posited the influence of Pollock’s theory of state capitalism on Horkheimer and Adorno’s late work). Wellmer and Jay also argued that Habermas’s approach to Critical Theory—which linked a normative democratic theory no longer reliant on class struggle to empirical social research — echoed and improved upon the ISR’s initial approach to critical theory, representing a way out of what they argued were the pessimistic social theoretical cul-de-sac Horkheimer, Adorno (and even Marcuse) had created. Both of these elements of Wellmer’s and Jay’s work were echoed by Trent Schroyer, and others.

Importantly, Jay’s account of Horkheimer and Adorno’s late work was criticized by James Schmidt, and Russell Jacoby. Jacoby also argued that Horkheimer’s Authoritarian State and Adorno’s later work on culture and subjectivity were a deepening of Horkheimer and Adorno’s interpretation of the critique of political economy, not a break. North American critical theorists drew extensively on these aspects of Horkheimer and Adorno’s work. Cecilia Sebastian shows that The Authoritarian State was important for Angela Davis’s initial work on fascism and abolition. Jacoby, along with others associated with Telos, integrated these aspects of Horkheimer and Adorno’s work with Marcuse (perhaps the key influence on this approach to Critical Theory) and other Western Marxists to develop what Ben Agger termed “North American Marxism.”

The rise of what Murray Bookchin called “Habermas Ltd” in the late 1970s and early 1980s marginalized this understanding and approach to Frankfurt School Critical Theory. Today, despite efforts by Andrew Feenberg and Michael J. Thompson to maintain it, this approach is largely forgotten. This is because Martin Jay, Seyla Benhabib, Jean Cohen, Andrew Arato, Richard Bernstein, Nancy Fraser, Thomas McCarthy and others championed and deepened a Habermasian approach to critical theory that saw Habermas’s work and his criticism of Horkheimer and Adorno’s critical theory—particularly following the two volume Theory of Communicative Action—as a definitive paradigm shift, which supplanted the first generation’s inadequate normative grounding and totalizing social theory for the intersubjective normative democratic theory of communicative reason and social theory of systematic differentiation. This Habermasian conception of Critical Theory became synonymous with Frankfurt School Critical Theory in the USA.

In the United Kingdom, Perry Anderson’s “balance sheet” on Western Marxism included an account of the development of Horkheimer and Adorno’s critical theory which resembled that of Wellmer and Jay. Anderson argued that the New Left should turn away from the culturalism of Western Marxism towards the classical Marxist political economy.

In opposition to the revival of classical Marxist political economy that ensued, notable figures in America, including Moishe Postone, Patrick Murray, and Tony Smith, and the UK, such as Chris Arthur, John Holloway, and Simon Clarke, developed a different interpretation of Marxian political economy—the critique of political economy as a critical social theory. This approach to political economy drew inspiration from Adorno and Horkheimer as well as Horkheimer and Adorno-inspired interpretations of Marx first developed by their students: Alfred Schmidt, Hans-Jurgen Krahl, Hans-Georg Backhaus, and Helmut Reichelt. Holloway, Clarke, and other figures later associated with Open Marxism also drew on the West German state derivation debate (launched as a critique of Habermas), Detlev Claussen, and the Krahl-inspired work of Italian Autonomism.

The 3-volume Sage Handbook of Frankfurt School Critical Theory, which I co-edited with Beverley Best and Werner Bonefeld, provided an overview of Frankfurt School Critical Theory with and against the Anglophone-branded identity of Habermasian Critical Theory as synonymous with Frankfurt School Critical Theory by focusing on the hegemonic Habermasian conception of Critical Theory alongside its subterranean lineages.

III

Consequently, Scheuerman’s and Moyn’s criticisms of contemporary Habermasian Frankfurt School Critical Theory do not apply to contemporary work in political economy that furthers the development of the subterranean lineages of Frankfurt School Critical Theory.

In the first place, recent scholarship in this vein has pushed back against the narrative Scheuerman evokes of the development of Horkheimer and Adorno’s critical theory and argued that a unique conception of political economy, developed by Horkheimer and then Adorno, is central to Frankfurt School Critical Theory.

As James Schmidt and Dirk Braunstein have shown, the influence of Pollock’s state capitalism was less influential on Adorno than Jay, Dubiel and Scheuerman contend. As Braunstein, Marcel Stoetzler, and Massimiliano Tomba have demonstrated Dialectic of Enlightenment did not abandon Marx, but provided an immanent critique of Marxism that deepened Horkheimer and Adorno’s interpretation of the critique of political economy. Moreover, Adorno’s lectures, notably Philosophy and Sociology and Philosophical Elements of Society, reveal the influence of Neumann on his thinking and show how his social theory drew on the empirical research that the Institute conducted under his leadership. Finally, as Braunstein, Bonefeld, and my own work have shown the critique of political economy was key to Adorno’s late critical theory.

As this literature also shows, rather than Pollock’s theory of state capitalism rendering political economy “marginal” to post-war critical theory, the late work of Adorno deepened and expanded the early Horkheimer’s interpretation of the relationship between the critique of political economy and the critical theory of society in two ways: (1) further developing the interpretation of the critique of political economy as a theory of social constitution and the social domination of capital accumulation (2) continuing to extend the critique of political economy into a critical theory of society. In further contrast to Scheuerman, the modifications to capitalist society that Adorno’s social theory incorporated in his critique of late capitalism as a negative totality were not conceived of as overcoming capitalism’s economic contradictions, but as counteracting tendencies that were derived from the inherent contradictions, antagonisms, and crisis tendencies of capital accumulation.

In the second place, there is a wealth of work in political economy that builds on this conception of Frankfurt School Political Economy, addressing the lacuna and topics that Scheuerman and Moyn point to.

One approach consists of theoretically minded work that continues to develop the interpretation of the critique of political economy as a critical social theory pioneered by Horkheimer, Adorno, and their students. As Scheuerman indicates was the case for the early Frankfurt School up to 1941, this work “pays close attention to contemporary trends in political economy and debates among economists and social scientists” and incorporates them into the development of the critique of political economy as a critical social theory. Consequently, rather than merely providing important interpretations of Marx and Adorno, recent important work by Tony Smith, Patrick Murray and Jeanne Schuler, Werner Bonefeld, Beverley Best, Ana Cecilia Dinerstein, Frederick Harry Pitts, and Charles Prusik has also developed important critiques of economics and social science methodology, the capitalist state, globalization, Keynesianism, neoliberalism, periodization, globalization, technology, financialization, and reformism.

Another approach shows that the interpretation of the critique of political economy as a critical social theory has impacted empirically minded work in political economy. This work also addresses developments that Moyn rightly argues the predominant conception of critical theory has missed. Aaron Benanav, Alexis Moraitis, Christos Memos, and Fabian Arzuaga have focused on economic crisis. Jack Copley on neoliberalism. Ilias Alami has written on the international system and the new state capitalism. Javier Moreno Zacarés on housing. Kirstin Munro on household production.

However, just as Adorno did not treat Marx as a “bible,” neither does this current critical theory scholarship treat Adorno’s work as one. It brings together Adorno and Marx (Christian Lotz, Charlotte Baumann). It also expands on such a notion of Frankfurt School Critical Theory by integrating accounts of gender (Nathan Duford, Amy De’ath, Marina Vishmidt), race and antisemitism (Hylton White, Marcel Stoetzler, Jonathon Catlin,), the environment and climate politics (Jacob Blumenfeld, Alexander Stoner, Carl Cassegaard, and Rob Hunter), public opinion (Eric-John Russell), terrorism (Verena Erlenbusch-Anderson), and surplus citizens (Dimitra Kotouza).

My own work has sought to critique the predominant conception of the Frankfurt School and draw Horkheimer and Adorno’s critical theory and the critique of political economy as a social theory together with the work that expands on it for the sake of developing a critical theory of the negative totality of contemporary capitalist society. The book series I co-edit, Critical Theory and the Critique of Society, also publishes work in this vein of Frankfurt School Critical Theory.

It is not, then, that the younger generations have no interest in Frankfurt Critical Theory as Moyn indicates. Nor, if one recognizes the abundance of work that I have pointed to as Frankfurt School Critical Theory, is there a lacuna in the relationship between Frankfurt School Critical Theory and political economy, or a lack of critical theories of contemporary capitalism that draw on political economy. Instead, there is a lack of interest in Habermasian Critical Theory among younger generations and a lack of recognition that these subterranean traditions amount to Frankfurt School Critical Theory by those who work in Habermasian Critical Theory. This lacuna no doubt contributes to the negative consequences for contemporary Frankfurt School Critical Theory that Scheuerman and Moyn point to. I hope that this blog post will contribute to an opening up of what is accepted as Frankfurt School Critical Theory and that this important contemporary work I point to will play a role in its revitalization.

Chris O’Kane is an Adjunct Associate Professor of Economics & Finance at St. John’s University and co-editor of the Critical Theory and Critique of Society Book Series. He is working on a book on Horkeheimer and Adorno’s heterodox Marxian Critical Theories of Social Domination and the development of the Critique of Political Economy as a Critical Social Theory.

Edited by Jonas Knatz and Artur Banaszewski

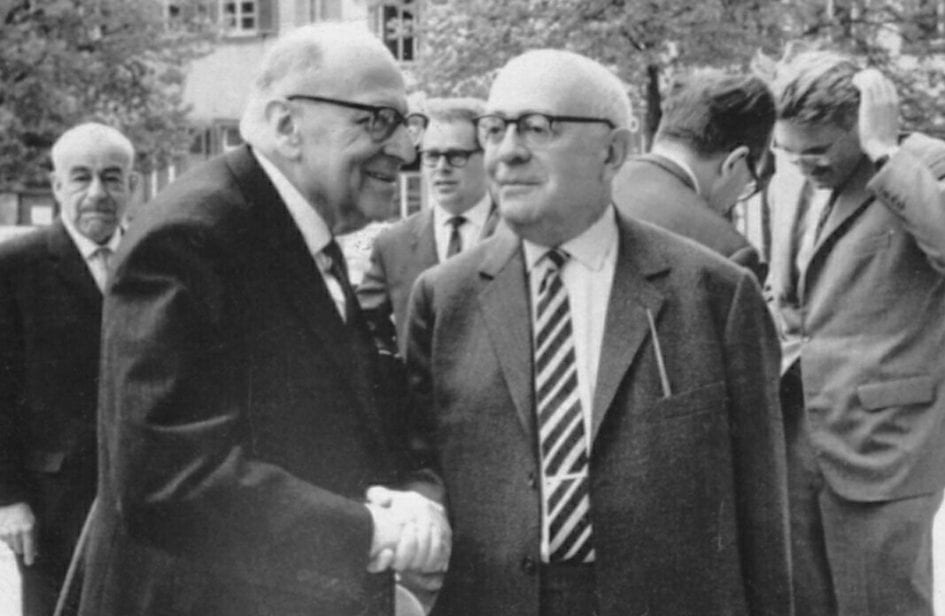

Featured image: Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno in Heidelberg in 1964, in the background: Jürgen Habermas. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

1 Pingback